Crescendo of polyphony

Peter Phillips on a Zambian chamber choir which decided to perform Byrd, Tallis and Tippett

As calling cards go, renaissance polyphony would not seem to promise a ticket to anywhere much, unless to heaven. When I started giving concerts in 1973, the received wisdom on the subject, even in the UK, was that whole concerts of it would never draw an audience. How true that was. But slowly perceptions have changed, and not only in the UK. With something of a crescendo, the opportunities to conduct this repertoire have multiplied, taking me to some very unlikely places. So far as Africa goes I had previously worked only in Fez and Cairo; never in any of the sub-Saharan countries. Last week Byrd’s Mass for Four Voices was heard in concert — I assume for the first time — in Lusaka, Zambia.

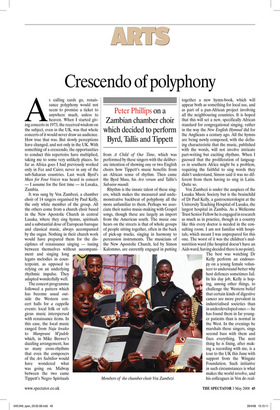

It was sung by Vox Zambezi, a chamber choir of 14 singers organised by Paul Kelly, the only white member of the group. All the others come from a church choir based in the New Apostolic Church in central Lusaka, where they sing hymns, spirituals and a substantial dose of European baroque and classical music, always accompanied by the organ. Nothing in their church work would have prepared them for the disciplines of renaissance singing — tuning between themselves without accompaniment and singing long legato melodies in counterpoint, as opposed to relying on an underlying rhythmic impulse. They adapted wonderfully well.

The concert programme followed a pattern which has become usual outside the Western concert halls for a cappella events: local folk or religious music interspersed with renaissance items. In this case, the local music ranged from Naja kwako to Mangwani M’pulele which, in Mike Brewer’s dazzling arrangement, has so many cross-rhythms that even the composers of the Ars Subtilior would have wondered what was going on. Midway between the two came Tippett’s Negro Spirituals from A Child of Our Time, which was performed by these singers with the deliberate intention of showing one or two English choirs how Tippett’s music benefits from an African sense of rhythm. Then came the Byrd Mass, his Ave verum and Tallis’s Salvator mundi.

Rhythm is the innate talent of these singers, which makes the measured and undemonstrative backbeat of polyphony all the more unfamiliar to them. Perhaps we associate their native music-making with Gospel songs, though these are largely an import from the American south. The music one hears on the streets is that of whole groups of people sitting together, often in the back of pick-up trucks, singing in harmony to percussion instruments. The musicians of the New Apostolic Church, led by Simon Kalommo, are currently engaged in putting together a new hymn-book, which will appear both as something for local use, and as part of a pan-African project involving all the neighbouring countries. It is hoped that this will set a new, specifically African standard for congregational singing, rather in the way the New English Hymnal did for the Anglicans a century ago. All the hymns are being newly composed, with the defining characteristic that the music, published with the words, will not involve intricate part-writing but exciting rhythms. When I guessed that the proliferation of languages in southern Africa might be a problem, requiring the faithful to sing words they didn’t understand, Simon said it was no different from them having to sing in Latin. Quite so.

Vox Zambezi is under the auspices of the Lusaka Music Society but is the brainchild of Dr Paul Kelly, a gastroenterologist at the University Teaching Hospital of Lusaka, the largest hospital in Zambia. As a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow he is engaged in research as much as in practice, though in a country like this every doctor is needed in the consulting room. I am not familiar with hospitals, which meant I was unprepared for this one. The worst of it was the children’s malnutrition ward (the hospital doesn’t have an Aids ward, having decided there is no point). The best was watching Dr Kelly perform an endoscopy on a young female volunteer to understand better why host defences sometimes fail. In his day job, Kelly is hoping, among other things, to challenge the Western belief that certain kinds of digestive cancer are more prevalent in industrialised societies than in underdeveloped ones — he has found them in far younger patients than is normal in the West. In the evenings he marshals these singers, sings second bass with them and fixes everything. The next thing he is fixing, after making a recording with me, is a tour to the UK this June with support from the Wingate Foundation. Such initiative in such circumstances is what makes the world revolve, and his colleagues in Vox do real ise how lucky they are. When I asked what gave him the idea of starting the group in the first place, he quoted something I have heard several times before in differing contexts: years ago the Registrar of Societies in Zambia declared that classical Western music was not for the common people, it was an irrelevance. The poshest version of this kind of high-handed, inverted paternalism that I ever encountered was when the Secretary of Chamber Music New Zealand stood up in front of an Australian audience and declared, ‘New Zealand people do not like early music.’ Out of such irritations good things can come.

But the fascinating question to me is why Vox Zambezi, and many groups like them elsewhere in the world, feel it necessary to include renaissance items in their concerts at all. It is as if they feel the need to prove themselves in the currency of an international gold standard, before performing the music which is theirs and which everyone knows they can sing well (or, if they can’t, no one can). For me it is like hearing English spoken fluently among people who have their own language, but regularly choose not to use it. If I am representing the modern status of polyphony accurately here, it is an astonishing turnaround from the situation as I found it in 1973. Every music undergraduate then knew that Byrd was Number One Polyphonist; but we didn’t expect to be hearing him sung years later in all four corners of the globe by people for whom Latin is not only dead, but also never lived.

For information about Vox Zambezi’s UK tour, visit www.voxzambezi.net

Previous page

Previous page