FULLY PAID-UP CONSERVATIVE

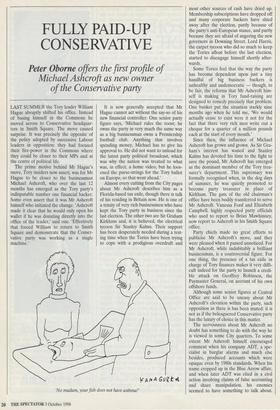

Peter Oborne offers the first profile of Michael Ashcroft as new owner of the Conservative party LAST SUMMER the Tory leader William Hague abruptly shifted his office. Instead of basing himself in the Commons he moved across to Conservative headquar- ters in Smith Square. The move caused surprise. It was precisely the opposite of the policy adopted by successive Labour leaders in opposition: they had focused their fire-power in the Commons where they could be closer to their MPs and at the centre of political life.

The prime motive behind Mr Hague's move, Tory insiders now assert, was for Mr Hague to be closer to the businessman Michael Ashcroft, who over the last 12 months has emerged as the Tory party's indisputable number one financial backer. Some even assert that it was Mr Ashcroft himself who initiated the change. 'Ashcroft made it clear that he would only open his wallet if he was donating directly into the office of the leader,' said one. 'Effectively that forced William to return to Smith Square and demonstrate that the Conser- vative party was working as a single machine.' It is now generally accepted that Mr Hague cannot act without the say-so of his new financial controller. One senior party figure says, 'Michael rules the roost; he owns the party in very much the same way as a big businessman owns a Premiership football club. Anything that involves spending money, Michael has to give his approval to. He did not want to unload for the latest party political broadcast, which was why the nation was treated to what was, in effect, a home video, but he loos- ened the purse-strings for the Tory ballot on Europe, so that went ahead.'

Almost every cutting from the City pages about Mr Ashcroft describes him as a Florida-based tax exile, though there is talk of his residing in Britain now. He is one of a trinity of very rich businessmen who have kept the Tory party in business since the last election. The other two are Sir Graham Kirkham and, it is believed, the electrical tycoon Sir Stanley Kalms. Their support has been desperately needed during a test- ing time when the Tories have been trying to cope with a prodigious overdraft and No madam, your fish does not have asthma!' most other sources of cash have dried up. Membership subscriptions have dropped off and many corporate backers have shied away after the election, partly because of the party's anti-European stance, and partly because they are afraid of angering the new governors in Downing Street. Lord Harris, the carpet tycoon who did so much to keep the Tories afloat before the last election, started to disengage himself shortly after- wards.

Some Tories feel that the way the party has become dependent upon just a tiny handful of big business backers is unhealthy and undemocratic — though, to be fair, the reforms that Mr Ashcroft him- self is making in Tory fund-raising are designed to remedy precisely that problem. One banker put the situation starkly nine months ago when he told me, 'We would actually cease to exist were it not for the fact that three very rich men write out a cheque for a quarter of a million pounds each at the start of every month.'

Since then, the influence of Michael Ashcroft has grown and grown. As Sir Gra- ham's interest has waned and Stanley Kalms has devoted his time to the fight to save the pound, Mr Ashcroft has emerged as the dominant member of the Tory trea- surer's department. This supremacy was formally recognised when, in the dog days of summer, he was quietly promoted to become party treasurer in place of Kirkham. The guts of the old chairman's office have been bodily transferred to serve Mr Ashcroft. Vanessa Ford and Elizabeth Campbell, highly respected party officials who used to report to Brian Mawhinney, now report to Ashcroft in his Smith Square office.

Party chiefs made no great efforts to publicise Mr Ashcroft's move, and they were pleased when it passed unnoticed. For Mr Ashcroft, while indubitably a brilliant businessman, is a controversial figure. For one thing, the presence of a tax exile in charge of Tory finances makes it very diffi- cult indeed for the party to launch a credi- ble attack on Geoffrey Robinson, the Paymaster General, on account of his own offshore funds.

Although some senior figures at Central Office are said to be uneasy about Mr Ashcroft's elevation within the party, such opposition as there is has been muted: it is not as if the beleaguered Conservative party has the luxury of choice in this matter.

The nervousness about Mr Ashcroft no doubt has something to do with the way he is viewed in some City quarters. To some extent Mr Ashcroft himself encouraged comment when his company ADT, a spe- cialist in burglar alarms and much else besides, produced accounts which were opaque even by 1980s standards. When his name cropped up in the Blue Arrow affair, and when later ADT was cited in a civil action involving claims of false accounting and share manipulation, his enemies seemed to have something to talk about. But Mr Ashcroft rubbished the claims and there are no grounds for believing that there was ever anything behind the charges laid at Mr Ashcroft's door.

But it is still hard to find City sources who are willing to flatter him. One serious- ly rich financier says that while Mr Ashcroft has made a great deal of money for himself, the returns to his shareholders are not in the same league.

Mr Ashcroft has done very well indeed for himself, much better than is generally realised. Last year he made a personal profit of £150 million when he sold ADT to a United States buyer. But his biggest killing has been made in banking. He pur- chased the Bank of Belize for one dollar and, it is said, recently disposed of it for an earth-shattering $500 million. Those who know him well reckon that he is not far short of being a dollar billionaire. In other words, he is in a position to sort out the Tory party's grievous financial problems out of petty cash.

But what makes him do it? Why can't he, like other rich men, be content to plough his money into yachts and race- horses? The answer may lie in a new- found craving for acceptance.

Mr Ashcroft has always seemed resent- ful that unlike many less successful busi- nessmen he has not been fully welcomed into establishment circles. While nobody has ever doubted his brilliance, until very recently he could never remotely have been described as an establishment figure. He can be now, and the case of Michael Ashcroft is a model for others wanting to make the grade in British society. Charitable activity was the key, and in particular his role in setting up Crimestop- pers. 'The way that Michael has poured time, money and effort into his Crimestop- pers charity is absolutely marvellous,' declared a friend. Praised by police and community workers and supported by Jack Straw, Crimestoppers is, nevertheless, very much Mr Ashcroft's own initiative. Its list of trustees includes former policemen, city figures and politicians — a public statement, if ever there was one, that Mr Ashcroft is now at the heart of the British establishment. They include Sir Denis Thatcher; David Mayhew, the Cazenove partner; the industrialists Sir Ronnie Hempel and Sir Eric Pountain; Sir Peter Imbert; Sir Kenneth Newman; and Lord Rees, the former Labour home secretary.

On 1 December, at the Savoy, most of these figures will be present at a great Crimestoppers fund-raising ball. Perhaps now is the time to ask whether it is the Tory party that is lending its name to make Mr Ashcroft accepted, or whether it is the other way around.

Peter Obome is political columnist of the Express.

Previous page

Previous page