ARTS

Asia in Crawley

Anatol Lieven visits a festival of the Indian performing arts in Britain It is no longer necessary to travel 6,000 miles to encounter the highest tradition of the Indian performing arts. In July I went to Crawley, where the new Hawth theatre complex held a festival called Nayee Kiran as part of its opening season.

The gulf between the Indian (more properly, South Asian) and Western cultu- ral traditions in the performing arts is of course enormous. It will probably take decades at least to create effective synth- eses — even assuming that these are desirable. In the meantime, however, many of these arts are at least appreciable for their sheer beauty, even if a deeper cultural understanding is missing. This is true of Indian dance, the beauty of which — well, of the dancers, anyway — is immediately evident to a Western audi- ence. Indian dance has hitherto differed from the Western ballet in not trying to tell extended stories, but to express particular episodes or even simply moods. It appears both more fluid and more precise than the ballet, and somehow closer to the ground. The stamping movement which sets the anklets jingling provides an essential part of the rhythm. The whole appearance of the dancers is more solid, less ethereal than that of their Western counterparts.

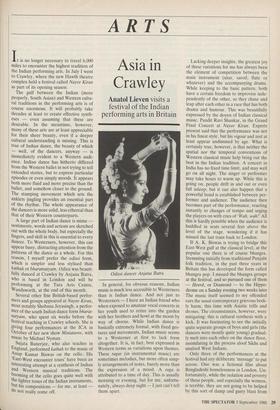

A large part of Indian dance is mime sentiments, words and actions are sketched out with the whole body, but especially the fingers, and skill in this is essential to every dancer. To Westerners, however, this can appear fussy, distracting attention from the patterns of the dance as a whole. For this reason, I myself prefer the odissi form, which is simpler and less stylised than kathak or bharatnatyam. Odissi was beauti- fully danced at Crawley by Anjana Batra, who is based in London and will be performing at the Tara Arts Centre, Wandsworth, at the end of this month.

Several other fine British-based perfor- mers and groups appeared at Nayee Kiran, most notably Shobana Jeyasingh, a perfor- mer of the south Indian dance form bharat- natyam, who spent six weeks before the festival teaching in Crawley schools. She is giving four performances at the ICA in October of her new show Miniatures, with music by Michael Nyman. Sujata Banerjee, who also teaches in England, performed kathak to the music of Anup Kumar Biswas on the cello. His .East-West encounter tours' have been an Interesting attempt at a synthesis of Indian and Western musical traditions. The booming of the cello goes quite well with the lighter tones of the Indian instruments, but his compositions — for me, at least do not really come off.

Odissi dancer Anjana Batra

In general, for obvious reasons, Indian music is much less accessible to Westerners than is Indian dance. And not just to Westerners — I have an Indian friend who when exposed to amateur vocal concerts in her youth used to retire into the garden with her brothers and howl at the moon by way of chorus. While Indian dance is basically extremely formal, with fixed ges- tures and movements, Indian music seems to a Westerner at first to lack form altogether. It is, in fact, best expressed in Western terms as variations upon themes. These ragas (in instrumental music) are sometimes melodies, but more often simp- ly arrangements of notes, barely more than the expression of a mood. A raga is attributed to a time of day. This is usually morning or evening, but for me, unfortu- nately, always deep night — I just can't tell them apart. Lacking deeper insights, the greatest joy of these variations for me has always been the element of competition between the main instrument (sitar, sarod, flute or whatever) and the accompanying drums. While keeping to the basic pattern, both have a certain freedom to improvise inde- pendently of the other, so they chase and leap after each other in a race that has both drama and humour. This was beautifully expressed by the doyen of Indian classical music, Pandit Ravi Shankar, in the Grand Final Concert at Nayee Kiran. Experts present said that the performance was not in his finest style, but his vigour and zest at least appear undimmed by age. What is certainly true, however, is that neither the spatial nor the temporal conventions of Western classical music help bring out the best in the Indian tradition. A concert in India has no fixed time limit, and may well go on all night. The singer or performer may take hours to warm up. While this is going on, people drift in and out or even fall asleep; but it can also happen that a powerful bond is established between per- former and audience. The audience then becomes part of the performance, reacting instantly to changes of tempo and urging the players on with cries of `Wah, wah!' All this is hardly possible when the audience is huddled in seats several feet above the level of the stage, wondering if it has missed the last train back to London.

If A. K. Biswas is trying to bridge this East-West gulf at the classical level, at the popular one there is of course bhangra. Stemming initially from traditional Punjabi folk tradition, in the past three years in Britain this has developed the form called bhangra pop. I missed the bhangra groups at the festival, and so pursued one of them — Heerd, or Diamond — to the Hippo- drome on a Sunday evening two weeks later The music itself seemed to my offended ears the usual contemporary grievous bodi- ly harm, this time with Asiatic trills and drones. The circumstances, however, were mitigating: this is cultural synthesis with a kick. It was fascinating to see the initially quite separate groups of boys and girls (the dancers were mostly quite young) gradual- ly melt into each other on the dance floor, assimilating in the process aloof Sikhs and unaloof West Indians.

Only three of the performances at the festival had any deliberate 'message' to put across. One was a fictional film about Bangladeshi homelessness in London. Un- fortunately, while the isolation and poverty of these people, and especially the women, is terrible, they are not going to be helped by this sort of damp and gusty blast from the cellars of agitprop. It contrasted sadly with the other pieces at the festival, simply in that they were well done, and it is not. Then there was the alarmingly titled A Fiercer Kind of Being, a series of dances on themes from the Indian myths, dealing with 'women's responses to problems of integrity and justice'. This may sound a bit grim, but it was actually one of the most beautifully staged and performed pieces at the festival. It deserves to have an effect on its audiences. This group is based in Birmingham, and will be performing in the autumn in Cornwall and Yorkshire.

Finally, Nayee Kiran provided a preview for a splendid children's book by Aryan Kumar called The Heartstone Odyssey which is to appear in the autumn, and is at present being danced across Britain — Sitakumari is performing extracts from it in schools. Having been refused by the more usual publishers, it is being printed by a company called Allied Mouse. Mice, in- deed, play the leading role in it — anti- racist mice. It is certainly an excellent blow against racism — both on the Jesuit princi- ple of 'catch 'em young', and because it is so excitingly written. It deserves to be a great success. As a fine work of art in its own right, Sitakumari's performance of the story fitted in well with the spirit of the Nayee Kiran festival as a whole. Nayee Kiran could also be taken as a sort of statement about Asian culture in Britain. It was neither aggressive nor resentful; it was beautifully phrased, but it was also firm: J'y suis, j'y reste.

Previous page

Previous page