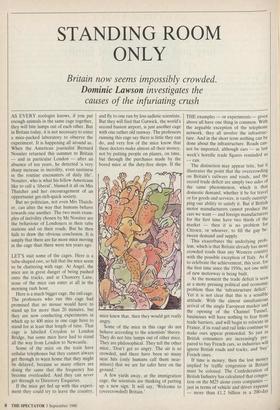

STANDING ROOM ONLY

Britain now seems impossibly crowded.

Dominic Lawson investigates the

causes of the infuriating crush

AS EVERY zoologist knows, if you put enough animals in the same cage together, they will bite lumps out of each other. But in Britain today, it is not necessary to enter a mice-packed laboratory to observe the experiment. It is happening all around us. When the American journalist Bernard Nossiter returned this summer to Britain — and in particular London — after an absence of ten years, he detected 'a very sharp increase in incivility, even nastiness in the routine encounters of daily life'. Nossiter, who is what his fellow Americans like to call a 'liberal', blamed it all on Mrs Thatcher and her encouragement of an opportunist get-rich-quick society.

But no politician, not even Mrs Thatch- er, can alter the way that humans behave towards one another. The two main exam- ples of incivility chosen by Mr Nossiter are the behaviour of Londoners in their tube stations and on their roads. But he then fails to draw the obvious conclusion. It is simply that there are far more mice moving in the cage than there were ten years ago.

LET'S visit some of the cages. Here is a tube-shaped one, so full that the mice seem to be chattering with rage. At Angel, the mice are in great danger of being pushed onto the tracks, and at Chancery Lane, none of the mice can enter at all in the morning rush hour.

Here is a much bigger cage, the rail cage. The professors who run this cage had promised that no mouse would have to stand up for more than 20 minutes, but they are now conducting experiments in which up to 400 mice in one cage have to stand for at least that length of time. That cage is labelled Croydon to London Bridge, but some mice have had to stand all the way from London to Newcastle.

Some of the mice on the train have cellular telephones but they cannot always get through to warn home that they might be delayed, because so many others are doing the same that the frequency has become overloaded. And they can never get through to Directory Enquiries.

If the mice get fed up with this experi- ment they could try to leave the country, and fly to one run by less sadistic scientists. But they will find that Gatwick, the world's second busiest airport, is just another cage with one rather old runway. The professors running this cage say there is little they can do, and very few of the mice know that these doctors make almost all their money, not by putting people on planes, on time, but through the purchases made by the bored mice at the duty-free shops. If the

mice knew that, then they would get really angry.

Some of the mice in this cage do not behave according to the scientists' theory. They do not bite lumps out of other mice. They are philosophical. They tell the other mice, 'Don't get so angry. The air is so crowded, and there have been so many near hits (only humans call them near- misses) that we are far safer here on the ground.'

A few yards away, at the immigration cage, the scientists are thinking of putting up a new sign. It will say, 'Welcome to (overcrowded) Britain.'

THE examples — or experiments — given above all have one thing in common. With the arguable exception of the telephone network, they all involve the infrastruc- ture. And in the short term nothing can be done about the infrastructure. Roads can- not be imported, although cars — as last week's horrific trade figures reminded us — can.

The distinction may appear trite, but it illustrates the point that the overcrowding on Britain's railways and roads, and the record trade deficit are simply two sides of the same phenomenon, which is that domestic demand, whether it be for travel or for goods and services, is vastly outstrip- ping our ability to satisfy it. But if British motor manufacturers cannot produce the cars we want — and foreign manufacturers for the first time have two thirds of the market — then it is no problem for Citroen, or whoever, to fill the gap be- tween demand and supply. This exacerbates the underlying prob- lem, which is that Britain already has more crowded roads than any Western country with the possible exception of Italy. As if to celebrate the achievement, this year, for the first time since the 1950s, not one mile of new motorway is being built. At the moment the trade deficit is seen as a mote pressing political and economic problem than the 'infrastructure deficit'. Yet it is not clear that this is a sensible attitude. With the almost simultaneous arrival of the single European market and the opening of the Channel Tunnel, businesses will have nothing to fear from trade barriers, and will begin to relocate in France, if its road and rail links continue to make ours appear primordial. So just as British consumers are increasingly pre- pared to buy French cars, so industries will ignore British roads and tracks, and 'buy, French ones.

If time is money, then the lost money implied by traffic congestion in Britain must be colossal. The Confederation of British Industry has calculated that conges- tion on the -M25 alone costs companies — just in terms of vehicle and driver expense — more than £1.2 billion in a 200-day

working year.

To some extent both industry and gov- ernment — as the originator of infrastruc- ture projects — have both been caught unawares by the rapidity of the growth in the economy in the past few years. And since, according to even the most ancient of economic textbooks, travel tends to grow at least one and a half times more than the underlying growth in an economy, this unpreparedness has had almost catas- trophic consequences for the infrastruc- ture's ability to cope.

In fact British industry has not been caught short in quite the way the Govern- ment has. Despite the remarkable and unpredicted five per cent growth rate, there is little bottlenecking in British fac- tories, with more than two thirds operating at below full capacity. British industry is now preparing to expand dramatically, planning this year to spend 15 per cent more, on investment in manufacturing capacity than it did last year.

Yet the Government is only just begin- ning to authorise big new infrastructural projects — last month it finally announced the development of a new Thames crossing at Dartford and a desperately needed high-speed rail link to Heathrow. But still the typical new road project takes about 14 years from inception to completion, by which time the level of demand could render even the new infrastructure in- adequate.

This was classically the case with the M25 orbital motorway, first mooted in concept in 1908 by the Royal Commission on Transport as the panacea for London's traffic problems. In 1944 the Abercrombie report recommended the creation of up to four orbital London roads. All but one were killed off, the survivor being the M25, which opened less than two years ago and is now congested for at least five hours a day. The planners wanted four lanes. The Government saved money by sticking at three . . . and is now enlarging the motor- way at greater expense per mile than it cost to build ten years ago. Why should the Government have so underprovided for the infrastructure? The Government department responsible, Transport, is quick to disclaim responsibil- ity, at least for the problems of rail and air. It points out that neither the Civil Aviation Authority, nor British Rail, nor London Transport has ever been turned down in any spending requests brought to the De- partment of Transport over the past ten years. These are the organisations which we trust to run the public transport net- work, argue the civil servants of the Department of Transport, and if their forecasts are too low, that is not our fault. Naturally the buck is passed further down the line. British Rail, for example, can point out that its programme to scrap rolling stock which is now desperately needed stemmed from a report from the Monopolies and Mergers commission in 1981, which called for the action BR subsequently undertook.

Whoever is to blame, it is undeniable that transport has a lower political priority than virtually any other infrastructural project, whether it be hospital building or the electricity supply industry. The latter body has been ludicrously overfunded, leading to a surplus in generating capacity costing billions of pounds. Of course Mrs Thatcher would not have been able to see off Mr Scargill without all that 'useless' oil-fired capacity, so she probably regards it as billions well spent rather than billions wasted.

But the capacity was planned long be- fore Mr Scargill was ever heard of. The point is that angry commuters on the Croydon train are not seen as an election- losing issue. But the lights going out, and little old ladies dying of hypothermia is seen as an election loser.

Within the field of transport, govern- ments, both national and local, show a strong preference for current, rather than capital expenditure. This is partly because of the one-year funding cycle, which is so inimical to long-term planning, but also because the short-term political kudos to be gained from subsidising fares outweighs the value given by local politicians to the long-term benefits of a better network in ten years' time (when their opponents might be able to reap the benefits). A classic example of this sort of thinking was that of the now defunct GLC, when it gained local acclaim' for its cheap fares policy which encouraged many more into an ancient system that the GLC had little inclination to modernise, less to expand.

The GLC at least was able to raise money for its own pet projects. The Department of Transport, however, has to ask the Treasury nicely for its money. And until recently the Treasury's overriding objective appeared to be the reduction of public spending. When the bright sparks at the Department of Transport tried to get round this with proposals for infrastructure projects financed by the private sector, the Treasury responded with the so-called Ryrie rules. First enunciated by a former Treasury official, Sir William Ryrie, in 1981, these stated that if an infrastructural project was worth going ahead with, it should be financed by government, since, as the only borrower that could borrow at base rate, it could finance such projects more cheaply than anyone else.

If this view was consistently held throughout the Treasury, then, logically, the Government should have nationalised all British private sector companies, rather than privatised the public sector ones. But until this year, with the start of the Channel Tunnel project, and the Dartford- Thurrock bridge financed by Trafalgar House, the Treasury block on such pro- jects had been total. Although the Treasury insists that it has thus successfully prevented private sector financiers from taking the taxpayer — as opposed to the commuter — for a ride, it does seem that value for money has been overstressed, to the detriment of the travelling public. This is seen clearly in volume two of the Public Expenditure White Paper which shows that new publicly funded road projects currently under way are expected to yield a benefit to cost ratio of 1.9 to one, broadly equivalent, says the White Paper, to an economic return of 15 per cent in real terms. This is over twice the real rate of return of seven per cent demanded by the Treasury of such pro- jects.

If a private sector company found that its planned developments would average a rate of return of twice what it had targeted, it would — correctly — conclude that it was underinvesting the money entrusted to it by its shareholders. The Government ought to be able to draw similar conclu- sions from its own figures.

It is no longer possible, now that we have a Public Sector Lending Require- ment, to come up with the argument of the early part of the decade, that 'there is not enough money'. We have already arrived at the moment wistfully forecast in the conclusion of the 1984 Treasury Green Paper, The Next Ten Years: Public Ex- penditure and Taxation into the 1990s: 'It would of course always be open to the Government to decide, once the virtuous circle of lower taxes and higher growth had been established, to devote some of these resources to improved public services rather than reduced taxation.'

The Soviet-style planner might observe that the bottlenecks in the infrastructure could be solved not so much by increased spending but by a little bit of migration here, and a little bit of emigration there. The problem, after all, is hardly Malthu- sian. The British population is expected to increase only fractionally between now and the end of the century. If anything we shall just become older and slower. And while the South East is fit to burst, Burnley, or so the Guardian solemnly informed its read- ers last month, is disappearing'.

But as Alan Evans, professor of environ- mental economics at Reading university pointed out in a pamphlet published last month by the Institute of Economic Affairs, the British town planning system is responsible for the overcrowding problem in and around the cities, because it enables bureaucrats to obstruct development in rural areas. It all reminds Professor Evans of Chapter VII of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 'A mad tea-party': 'The table was a large one but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it. "No room! No room!" they cried out, when they saw Alice coming. "There's plenty of room!" said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in a large arm-chair at one end of the table.'

Previous page

Previous page