ARTS

Photography

Crown and camera: The Royal Family and Photography 1842-1910 (The Queen's Gallery, till next year)

A profession for royalty

Simon Blow

As the Japanese tourist clicks furiously away at scenes of Buckingham Palace, 100 years ago he might well have found the royal family clicking back at him. I do not know into what condition of shock this might throw the modern tourist, but it is precisely what Queen Victoria did when one raised his camera to her at Windsor. Since the arrival of Prince Albert into the country, the Royal Family have been ardent supporters of the photographic art. Two evenings a week, we are told, were usually kept free for Prince Albert and Queen Victoria to bring their albums up to date, and they were not just holiday snaps. Both were royal pioneers of the social conscience and collected beyond the straightforward scenic-view photographs of riots and disasters. Albert, for instance, collected daguerreotypes of the great Chartist meeting of 1848, while Victoria felt deeply for the wounded soldiers of the Crimean campaign, visited them in hos- pital at Chatham, and commissioned their photographs.

The result of this early royal patronage of the camera is a fascinating display of photographs currently on view at the Queen's Gallery. It is the first time the albums have been shown to the public and they tell us not only a little bit more about the lives of royals but offer us a virtual history of the camera's progress. The advent of photography came almost as a gift to the Consort's belief that the arts and science be reunited, and by the 1850s he was standing as patron of the newly- founded Photographic Society and taking a clear interest in photography's uses. It was thoroughly in keeping that the Prince should have been attracted by photographs that carried a moral message. One of the most curious exhibits is the Swedish-born 0. G. Rejlander's 'painted' photograph, The Two Ways of Life, after an allegorical picture by Raphael. The figures bent over booze amidst recumbent female nudes on one side are played against a group of hard-working folk, each plying a trade. So photography, by multiple reproduction, could influence the outlook of a nation: Prince Albert revelled in this warning against dissipation and ordered three copies, to be hung in his various dressing- rooms.

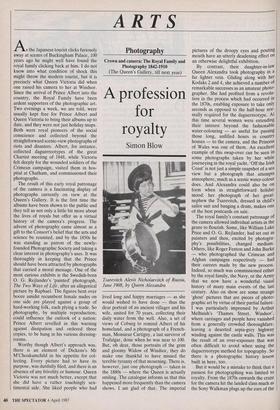

Worthy though Albert's approach was, there is an element of Dickens's Mr M'Choakumchild in his appetite for col- lecting. Every picture had to have its purpose, was dutifully filed, and there is an absence of any frivolity or humour. Queen Victoria was not much better, except that she did have a rather touchingly sen- timental side. She liked people who had Tsarevitch Alexis Nicholaevitch of Russia, June 1908, by Queen Alexandra lived long and happy marriages — as she would wished to have done — thus the dear portrait of an ancient villager and his wife, united for 70 years, collecting their daily water from the well. Also, a set of views of Coburg to remind Albert of his homeland, and a photograph of a French- man, Monsieur Cartigny, a last survivor of Trafalgar, done when he was near to 100. But, oh dear, those portraits of the grim and gloomy Widow of Windsor, they do make one thankful to have missed the terrible tyranny of that mourning. There is, however, just one photograph — taken in the 1880s — where the Queen is actually smiling. The catalogue informs us that this happened more frequently than the camera shows. I am glad of that. The imperial pictures of the droopy eyes and pouting mouth have an utterly deadening effect on an otherwise delightful exhibition.

By contrast, their daughter-in-law Queen Alexandra took photography in a far lighter vein. Gliding along with her Kodaks 2 and 4, she achieved a number of remarkable successes as an amateur photo- grapher. She had profited from a revolu- tion in the process which had occurred in the 1870s, enabling exposure to take only seconds as opposed to the half-hour nor- mally required for the daguerreotype. At this time several women were extending their interest beyond the fashionable water-colouring — so useful for passing those long, unfilled hours in country houses — to the camera, and the Princess of Wales was one of them. An excellent example of this swap-over can be seen in some photographs taken by her while journeying in the royal yacht. 'Off the Irish Coast' is not just a simple snapshot of a sea view but a photograph that attempts atmosphere, much as a scenic water-colour does. And Alexandra could also be on form when in straightforward holiday mood: her photograph of her great- nephew the Tsarevitch, dressed in child's sailor suit and banging a drum, makes one of the best postcards on sale. The royal family's constant patronage of the camera allowed individual artists in the genre to flourish. Some, like William Lake Price and 0. G. Rejlander, had set out as painters and then, excited by photogra- phy's possibilities, changed medium. Others, like Roger Fenton and John Burke — who photographed the Crimean and Afghan campaigns respectively — had their careers made by the new process. Indeed, so much was commissioned either by the royal family, the Navy, or the Army that we now have a wonderful visual history of many main events of the last century. Also on show are some strange `ghost' pictures that are pieces of photo- graphic art by virtue of their partial failure. I was particularly impressed by Arthur Melhuish's 'Thames Street, Windsor', where carriages and people have vanished from a generally crowded thoroughfare, leaving a deserted sepia-grey highway winding against the castle walls. This was the result of an over-exposure that was often difficult to avoid when using the daguerreotype method for topography. So there is a photographic history lesson built in here, too.

But it would be a mistake to think that a passion for photographing was limited to royalty. From the 1870s onwards the craze for the camera hit the landed class much as the Sony Walkman plugs up the ears of the young today. It was the era when every lady carried her visiting-book from house to house, not only getting the guests and hosts to sign their names but also sticking M Pictures of the house — say Blenheim, Penshurst, Crathes, or wherever — along- side photographs of picnicking groups, !oiling figures on lawns, a duchess perform- ing a Highland fling, and often inserted a cartoon, executed by the artist of the party, and with it a cryptic message. The cartoon Might be the distraught face of an elderly dowager who has lost at bridge or, as I once saw in one album, a cooking lobster With a fox's mask protruding from one end and the brush from the other. The caption beneath read, 'Such stuff as Dreams are made on!' I was sorry that of the few actual royal albums on view — notably one of Queen Alexandra's — none of this landed humour was on the page. The royal family are surely landed too, or are such digres- sions ____ photographic or otherwise considered not right for the public to see? Above everything, though, this is a Purists' exhibition about photography. If there is humour it is unintentional. I cannot take quite seriously Prince Alfred's photograph of his mother's theatrically mourning face staring up at the bust of the dead Consort, nor can I stomach all that sentimentality for the faces of little chil- d. run that Prince Albert so enjoyed. There is something about the Victorian obsession with family that grows sickly after a while. And the more so here, given the many overlapping connections of the House of Hanover; without this exhibition's magni- ficently informative catalogue, I would have been quite lost. But one need not quibble too much over Victoria and Albert's maudlin faith in the blood tie, since four years after this collection ends cousin was to war with cousin, and nearly every head they had attempted to unite was to fall. What really does delight me is to know at last the coinage behind those names that I would see embossed beneath the pictures of great- and great-great- grandparents. As a child, I would make rhymes to the lilting rhythms of the cou- plets: Andre Disderi, W. & D. Downey, Bassano & Vandyk, Negretti & Zambra, Elliott & Fry. Now I know better.

Previous page

Previous page