The Writers' Revolt

STANLEY UYS writes from Cape Town: Afrikaans writers in South Africa have chosen an inopportune time to start a revolution in their literature. Just when an authoritarian morality is stalking the land, a number of them are trying to break out of the sealed confines of their yolk traditions. Confronting them is a frightening phalanx of Afrikaans church and cultural leaders, for in the Afrikaner community which rules South Africa politics, religion and culture are all rolled up into one.

The AfrilCaners in South Africa number nearly two million—in a White population of three million and in a combined White and non- White population of sixteen million. Of the two million Afrikaners, a few hundred thousand or so are anglicised in varying degrees. It is to the residue that the Afrikaans writers must turn for their literary fulfilment, so, unlike their fellow- writers whose medium is English, the Afrikaans writers have only a limited market. If their books are rejected by publishers or banned (and many of the publishers are integral cogs in the compact Afrikaner nationalist machine), that is the end of it; if the English writers' books are

Ninety

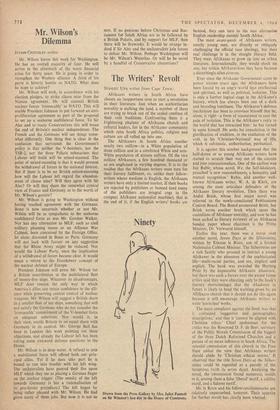

Drawn from the Press Gallery by Mrs. Juliet Pannett on Sir Winston's last day in the House of Commons. banned, they can turn to the vast alternative English. readership outside South Africa.

The most avant-garde of Afrikaans writers, mostly young men, are directly, or obliquely challenging the official race ideology, but their real challenge is in the straight literary field. They want Afrikaans to grow up into an urban literature. Internationally, they would shock no one, but within Afrikanerdom they have become a disturbingly alien element.

Ever since the Afrikaner Government came to power sixteen years ago, the Afrikaners have been forced by an angry world into intellectual and spiritual, as well as political, isolation. This is only a further logical stage in the Afrikaner's history, which has always been one of a dark and brooding loneliness. The Afrikaner's defence mechanism has been to convince himself that he, alone, is right--a form of reassurance to ease the pain of isolation. This is the Afrikaner's reply to the world that has ostracised him : he has turned in upon himself. He seeks his consolation in the glorification of tradition, in the exaltation of the yolk, in his 'Christian-National' way of life, which is calvinistic, authoritarian, puritanical.

It is against this sombre background that the half-dozen or so young Afrikaans writers have started to scratch their way out of the cocoon and into internationalism. One of the earliest was Jan Rabie, whose novel, We, the Self-ldolators, preached 'a new reasonableness, a humanity and mutual recognition.' Rabie, and another well- known Afrikaans writer, W. A. de Klerk, are among the most articulate defenders of the Afrikaner literary revolution. Then there was Andr6 Brink, whose first major novel was referred to the newly-constituted' Publications control Board. The Board exonerated Brink, but Brink wrote another book which upset the custodians of Afrikaner morality, and now he has been sacked as literary reviewer of an Afrikaans Sunday paper whose chairman is the Prime Minister, Dr. 'Verwoerd himself. Earlier this year, there was a storm over another novel, Seven Days at the Silbersteins, written by Etienne le Ronx, son of a former Nationalist Cabinet Minister. The Silbersteins are a rich family who proceed to instruct a young Afrikaner in the pleasures of the sophisticated life—multi-racial parties, and sex, implicit and explicit. The book was awarded the Hertzog Prize by the impeccable Afrikaans Akademie, but there was such a furore over the award (some critics said they were objecting only to the book's literary shortcomings) that the Akademie in future is likely to heed the warning• given by an Afrikaans church that it should not do this again because it will encourage Afrikaans writers to write 'norm-less' works.

The main complaint against the book was that it contained 'suggestive and pornographic descriptions,' and that it 'cannot be aligned with Chrittian ethics.' Chief spokesman for the critics was the Reverend D. F. de Beer, secretary of the Public Morals Commission of the biggest of the three Dutch Reformed Churches and a person of no mean influence in South Africa, The synodal commission of this church in the Free State added the view that Afrikaans writers should abide by 'Christian ethical norms.' It observed that' the title Seven Days at the Silber- steins could be regarded as a parody of, the Scriptures (with its seven days). Analysing the novel, the commission found numerous motifs in it, among them a false 'liberal' motif, a nihilist motif, and a Salome motif.

Mr. le Roux and his fellow-revolutionaries are relatively unperturbed, however. Their appetite for further revolt has clearly been whetted.

Previous page

Previous page