SAVE LONDON FROM PALUMBO

Gavin Stamp urges the Cabinet

not to return to the planning follies of the Sixties

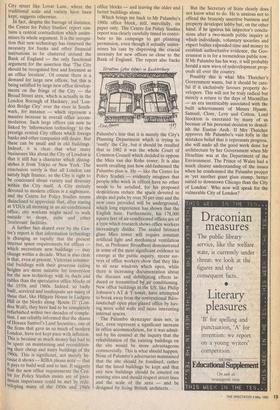

AS ONE of the instigators of the telex to Rome appealing to the Prince of Wales to ,save us all from Mr Peter Palumbo's Mansion House Square and 'stump', I ought to explain why the issue is so very important: why, that is, if the Government gives planning permission to a design which is reactionary as well as inappropri- ate, under the delusion that the proposed skyscraper is what the City of London actually wants or needs in the future, it represents a real threat to the conservation movement and to many other towns and cities. If the Government can endorse a scheme which will replace a network of City streets by a barren open space and a 19-storey tower designed by the late Mies van der Rohe, the 99-year-old German modernist, then clearly it is minded to give planning permission to almost anything.

All the architectural, conservation and planning arguments of the last two decades were marshalled and became sharply pola- rised at the long and expensive Mansion House Square public inquiry, which opened almost a year ago. At the time, as Mr Palumbo's knighted witnesses were wheeled in to reiterate an essentially Romantic and sentimental assertion about the 'timeless' classic excellence of a Mie- sian rectilinear conception as a work of art, and as a formidably argued and researched case against the proposals was built up by the City Corporation, by the GLC, SAVE Britain's Heritage and the Victorian Socie- ty, amongst others, few could believe that so essentially old-fashioned a design — conceived in the 1960s but representing the ideas of the 1940s — could ever get planning permission. Today, as the Gov- ernment is heard to echo the President of the RIBA's argument that conversation and planning control have gone 'too far', I am not at all optimistic Mr Palumbo's singlemindedness in pur- suit of his ideal always commanded respect if not sympathy. Now I must acknowledge his success as a lobbyist for, over the last year, he has been working hard to change the climate of opinion towards conserva- tion and modern architecture. Naturally the diehard modernists of the RIBA were always on his side, as were other property developers, but now there is a real danger that his facile arguments about progress

and change may not only sway the City Corporation but also influence the Gov- , ernment — which still has the power to realise Palumbo's personal dream of Man- sion House Square.

The occasion for this very well orches- trated campaign against 'excessive' con- servation was the publication of the City of London's Draft Local Plan in 1984. This may seem surprising, as the City has for long been notorious as the most conspi- cuous example of all that has gone wrong with British architecture since the war. The Luftwaffe damaged some two-fifths of the City of London but quite as much has been destroyed since, by a combination of crude planning and unrestricted development approved by the City Corporation.

Now, late — but not too late — in the day, the City's own Architecture and Plan- ning Department, under the leadership of Stuart Murphy, is attempting to repair the damage and redeem the City's reputation by carefully conserving the best of what is left and insisting on higher standards of design for new buildings. The new Draft Plan respects the diversity of the City while allowing for the change which must occur in one of the world's leading financial centres. In several respects the Plan does not go far enough (it accepts, for instance, more of the destructive road widenings which have already done so much unneces- sary damage in the City), but it is generally a moderate and sensible document, recom- mending policies which would be conven- tional in any other capital city.

Moderate as it may be, however, the City's Draft Plan has been deliberately savaged and portrayed as an attempt to fossilise the City as a museum — an accusation which must seem laughable to anyone who knows the City and can see how much large scale redevelopment is still going on. Mr Palumbo himself, amongst others, delivered a speech at the Mansion House which suggests that Mr Murphy is out of touch with the City and that con- servation will restrict London's eminence as a financial centre. The most serious attack, however, has come from that body known as the Centre for Policy Studies which was founded in 1974 by Margaret Thatcher and Keith Joseph. The Centre has published its own Comments on 'The City of London Draft Local Plan' of November 1984 and despite the curious disclaimer on the cover that 'nothing writ- ten here should be taken as representing the view of the Centre for Policy Studies', this document will clearly influence gov- ernment thinking.

I suppose it was inevitable that the free market ideas of modern Conservatism should eventually be applied to architecture and planning. This is sad as it ignores the huge achievement of conserva- tion societies in recent years in resisting the destructive effects of totalitarian socialist planning and unsympathetic architecture in favour of more civilised and popular en- vironments in which individuals can own their own houses and run their own businesses. But this success in protecting towns and cities has only been achieved through the help of law and planning controls. Pace Michael Manser, President of the RIBA, all civilised societies have always had planning or building regula- tions, but now the Centre for Policy Studies argues for the lifting of 'restrictive' planning controls to allow the land and development market in the City to operate freely. It even advocates the reduction of conservation areas — in which new de- velopment is never, in fact, restricted — and, worse, a reduction of the 'list of protected buildings', although it is not clear whether this means Statutorily Listed historic buildings or the City's own list of further buildings worthy of protection.

The Centre's report does make some valid criticisms of the Draft Plan in matters of detail, such as the fact that it sometimes uses out-of-date statistics when the City is constantly changing. Its central point is, however, that the Plan is based on asser- tion rather than fact and that its desire to respect the economic and functional varie- ty of the City — that is, small businesses, workshops and housing as well as high

finance — is a 'planning fashion'. How- ever, the statement that 'The Corpora-

tion's policies run the risk of ossifying large tracts of the City' is an assertion which a brief walk around the Square Mile can

soon explode. It is also an assertion, not a fact, that 'the functional requirements for

office space demanded by financial users cannot be met by refurbishing or even by reconstructing existing buildings, and pre- servation can impede site assembly for the larger buildings that are increasingly In demand'. The commercial success of the rehabilitation and rebuilding of an intimate City street like Lovat Lane, where the traditional scale and variety have been kept, suggests otherwise.

In fact, despite the barrage of statistics, the Centre for Policy Studies' report con- tains a central contradiction which under- mines its whole argument. It is the recogni- . tion that new technology has removed the necessity for banks and other financial institutions to be clustered around the Bank of England — the only functional argument for the assertion that `The City should be recognised first and foremost as an office location'. Of course there is a demand for large new offices, but this is being satisfied by large hew office develop- ments on the fringe of the City — the Broad Street area, which is actually in the London Borough of Hackney, and 'Lon- don Bridge City' over the river in South- wark, for instance — which represent a massive increase in overall office accom- modation. Such large offices can now be linked by 'information technology' to the prestige central City offices which foreign banks and other companies still desire. But these can be small and in old buildings. Indeed, it is clear that what many businesses like about the City of London' is that it still has a character which disting- uishes it from Tokyo or New York. The conclusion surely is that all London can satisfy high finance, so the City is right to be concerned about variety and diversity within the City itself. A City entirely devoted to modern offices is a nightmare, and the Centre for Policy Studies seems disinclined to appreciate that, after staring at VDUs all morning in an air-conditioned office, city workers might- need to walk outside to shops, pubs and other 'irrelevant' facilities.

A further fact skated over by the Cen- tre's report is that information technology is changing so rapidly that the present internal space requirements for offices — Which necessitate new buildings — may change within a decade. What is also clear is that, even at present, Victorian commer- cial buildings with their generous ceiling heights are more suitable for conversion for the new technology with its ducts and cables than the speculative office blocks of the 1950s and 1960s. Indeed, so badly built, serviced and inadequate are many, of these that, like Hil!gate House in Ludgate Hill Or the blocks along 'Route l'1' (Lon- don Wall), they have had to be completely refurbished within two decades of comple- tion. I am reliably informed that the shares of Horace Samuel's Land Securities, one of the firms that gave us so much of modern London, have not kept pace with inflation. This is because so much money has had to be spent on maintaining and recondition- ing their cheap and nasty buildings of the 1960s. This is significant, not merely be- cause it shows — RIBA please note -- that It pays to build well and to last. It suggests that the new office requirements the Cen- tre for Policy Studies insists are of para- mount importance could be met by rede- veloping many of the 1950s and,' 1960s office blocks — and leaving the older and better buildings alone.

Which brings me back to Mr Palumbo's 1960s office block, still, mercifully, on paper only. The Centre for Policy Studies report was clearly carefully timed to contri- bute to his campaign to get planning permission, even though it actually under- mines his case by disproving the crucial necessity for new offices so close to the Bank of England. The report also backs

Palumbo's line that it is merely the City's Planning Department which is trying to 'ossify' the City, but it should be recalled that in 1982 it was the whole Court of Common Council which decided to oppose the Mies van der Rohe tower. It is also worth recalling just how old-fashioned the Palumbo plan is. He — like the Centre for Policy Studies — evidently imagines that people who work in offices have no other needs to be satisfied, for his proposed demolitions reduce the space devoted to shops and pubs by over 50 per cent and the new ones provided will be underground, which long experience has shown that the English hate. Furthermore, his 178,000 square feet of air-conditioned offices are of a type which research shows office workers increasingly dislike. The sealed bronzed glass Mies tower will require constant artificial light and mechanical ventilation but, as Professor Broadbent demonstrated in some of the most significant evidence to emerge at the public inquiry, recent sur- veys of office workers show that they like to sit near windows which open, while there is increasing documentation about the diseases and debilitating effects in- duced or transmitted by air conditioning. New office buildings in the US, like Philip Johnson's AT & T tower, have attempted to break away from the conventional Bum- landschaft open plan glazed office by hav- ing more solid walls and more interesting internal spaces.

The Palumbo skyscraper does not, in fact, even represent a significant increase in office accommodation, for it was admit- ted by his counsel at the inquiry that the rehabilitation of the existing buildings on the site would be more advantageous commercially. This is what should happen. None of Palumbo's adversaries maintained that the site should be fossilised, rather that the listed buildings be kept and that any new buildings should be erected on

existing sites and should respect street lines and the scale of the area — and be designed by living British architects.

But the Secretary of State clearly does not know what to do. He is anxious not to offend the brazenly assertive business and property developer lobby but, on the other hand, if he ignores his inspector's conclu- sions after a two-month public inquiry at which individuals, voluntary societies and expert bodies expended time and money to establish authoritative evidence, the Gov- ernment is in for a tremendous public row. If Mr Palumbo has his way, it will probably herald a new wave of redevelopment prop- osals all over the country.

Possibly this is what Mrs Thatcher's Government wants, but it should be care- ful if it exclusively favours property de- velopers. This will not be truly radical but merely a return to the days of Macmillan — an era inextricably associated with the built achievements of Messrs Hymns, Samuel, Clore, Levy and Cotton. Lord Stockton is execrated by many of us because of his personal decision to demol- ish the Euston Arch. If Mrs Thatcher approves Mr Palumbo's vain folly in the mistaken belief that it represents progress, she will undo all the good work done for architecture by her Government when Mr' Heseltine was at the Department of the Environment. The Prince of Wales had a much clearer understanding of the issues when he condemned the Palumbo project as 'yet another giant glass stump, better suited to downtown Chicago than the City of London'. Who now will speak for the vulnerable City of London?

Previous page

Previous page