Someone beginning with P,

among others

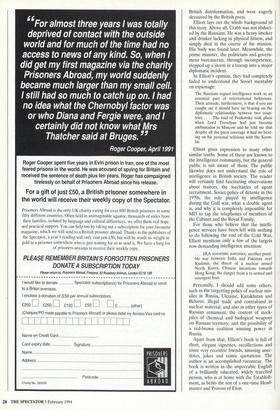

Oleg Gordievsky

WITH MY LITTLE EYE: OBSER- VATIONS ALONG THE WAY by Nicholas Elliott Michael Russell, £12.95, pp. 111 Nicholas Elliott is primarily known to the British public as the intelligence officer who visited Kim Philby in Beirut in January 1963, and did something which until then no one else had been able to do. He made Philby admit that he had been a KGB agent for years. Then, terrified by his con- fession, a panic-stricken Philby reported what had happened to his Russian masters, who evacuated him immediately to the Soviet Union.

Since then, various writers have time and again returned to this episode, fatuously blaming Elliott for failing to arrest Philby on the spot and to bring him back in hand- cuffs to London.

In his fascinating book, published some two years ago under the title Never Judge a Man by his Umbrella, Elliott did not dare to admit that he had worked for about 40 years in MI6, reaching the second or third top position in the Service. Nor could he acknowledge that he had been involved in the most improbable adventures and achievements of the British Secret Service on all five continents during the war and throughout the ensuing decades, and that he had witnessed its transformation from a group of imaginative amateurs into the most successful and competent intelligence service in the world.

Meanwhile, the epoch-making changes which have taken place in Europe have led to some dramatic innovations in Britain. The non-existent MI6 has been officially acknowledged, and we have learnt of Sir Colin McColl, its eloquent and intelligent Chief, and of Stella Rimington, the charm- ing and astute Head of MI5.

This still timid move towards publicity in the British civil service has enabled Elliott to reveal to us certain events from the intelligence world, in which he played a part, and to complete his second book, With My Little Eye.

When writing about the Philby saga, as it happened in the Lebanon, the author adds some interesting new details. Elliott learnt that Philby had fled to Moscow from Beirut while he was on a mission in Africa. He went back immediately to the Lebanon, where he and his wife Elizabeth surround- ed Philby's third wife Eleonor, whom Phil- by had left behind, with much care and attention, thus averting her immediate departure for Moscow, something which the KGB was secretly trying to achieve. There then followed a clumsy and unsuccessful attempt by the KGB and Philby to cast suspicion over Elliott's loyalty. He tells about certain aspects of what Philby was doing in Moscow, and about his encounter with Graham Greene in connection with the latter's notorious preface to Philby's book published in 1968.

Another important episode which Elliott ventures to make public, concerns the case of Commander Crabb. In 1956, Khrushchev and Bulganin paid their first official visit to Britain. They arrived on the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, which anchored in Portsmouth harbour. The Royal Navy wanted urgently to learn about certain equipment fitted below the stern of the vessel. MI6 and Nicholas Elliott, who was presumably responsible for the opera- tion, engaged Commander Crabb, a highly experienced frogman, to carry out this mis- sion. He never came back. The story leaked to the press. There was a scandal, actively backed up by the Labour opposition. Anthony Eden, then prime minister, refused to acknowledge the operation. MI6, and presumably Elliott as well, were subjected to harsh criticism. All this was aggravated by rumours either that Crabb had been killed by Soviet sailors, or that he had been kidnapped and taken back to the Soviet Union. These rumours were fostered by the KGB for years as anti-

British disinformation, and were eagerly devoured by the British press.

Elliott lays out the whole background td this story. Above all, Crabb was not abduct- ed by the Russians. He was a heavy smoker and drinker lacking in physical fitness, and simply died in the course of his mission. His body was found later. Meanwhile, the prime minister, the politicians and govern- ment bureaucrats, through incompetence, stepped up a storm in a teacup into a major diplomatic incident.

In Elliott's opinion, they had completely failed to understand the Soviet mentality on espionage:

The Russians regard intelligence work as an essential part of international behaviour. Their attitude, furthermore, is that if you are caught out it should have no bearing on the diplomatic relationship between two coun- tries . . . The trial of Penkovsky took place when Lord Trevelyan had just become ambassador in Moscow and he told me that despite all the press coverage it had no bear- ing on his personal relations with the Krem- lin.

Elliott gives expression to many other similar truths. Some of these are known to the intelligence community, but the general public is not aware of them. The public likewise does not understand the role of intelligence in British society. The reader will certainly find fascinating observations about traitors, the mechanics of agent recruitment, Soviet policy of détente in the 1970s, the role played by intelligence during the Gulf war, what a double agent is, and why it is completely impossible for MI5 to tap the telephones of members of the Cabinet and the Royal Family.

For those who believe that the intelli- gence services have been left with nothing to do following the end of the Cold War, Elliott mentions only a few of the targets now demanding intelligence attention:

. , . IRA terrorism; narcotics; another possi- ble war between India and Pakistan over Kashmir; the threat of a nuclear armed North Korea; Chinese intentions towards Hong Kong; the danger from a re-armed and resurgent Iran.

Personally, I should add some others, such as the targetting policy of nuclear mis- siles in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belorus; illegal trade and contraband in nuclear material, and also in other types of Russian armament; the content of stock- piles of chemical and biological weapons on Russian territory; and the possibility of a red-brown coalition winning power in Russia.

Apart from that, Elliott's book is full of short, elegant vignettes, recollections and some very eccentric friends, amusing anec- dotes, jokes and comic quotations. The author is an accomplished raconteur. The book is written in the impeccable English of a brilliantly educated, widely travelled person, who is at home with the Establish- ment, as befits the son of a one-time Head- master and Provost of Eton.

Previous page

Previous page