Exhibitions

Claude: the Poetic Landscape (National Gallery, till 10 April)

Roger Wagner: Paintings 1982-94 (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, till 27 March)

A need for Edens

Giles Auty

Athe director of the National Gallery, Neil MacGregor, remarks suc- cinctly in his foreword to a fine catalogue for an excellent exhibition: 'The pictures in this exhibition were painted by a subject of the German emperor who spoke French, lived in Italy and sold his works to the rich and powerful in Rome and Paris, Bohemia and Spain.' But the works of Claude Lor- rain (1604-1682) exercised a peculiar hold also on the sensibilities of British people, not just on later painters, such as Richard Wilson and Turner, but on those with the power and means to shape our countryside. `Come into the garden, Claude' was an air hummed metaphorically by landowners who sought to translate the artist's pastoral poetry into the palpable especially during the late 18th century.

All but one of the 28 paintings on show comes from an English home. These are backed by over 50 drawings. Claude was above all a convincing painter of landscape and light. His buildings and their sitings are slightly less credible and his human and bovine figures less believable still. General- ly the work serves to illustrate myth or leg- end and is, of course, imagined. Here the scale of groups of often tiny figures illus- trates a priority: the protagonists are essen- tially an excuse for their sublime surroundings. Claude tells the tale of Nar- cissus and Echo, Cephalus and Procris or of Christian saints, yet they are all dwarfed generally by the grandeurs of the land- scape. Has the human race as a whole always loved wonderful views?

Where the terrain is absolutely flat the Claudian vista becomes impossible; thus while the landscape of present-day Middle- sex may inspire a builder of airports, it is unlikely to lift the spirit of the romantic landscapist who usually requires heights and views. From his professional beginning, Claude studied nature and natural effects assiduously. Yet purely in naturalistic terms he was a better painter of distance than foregrounds, just as he was better at fronds than figures and clouds than cows.

Most of his compositions began about a cricket pitch away from the viewer, an irri- tating convention pursued thoughtlessly by popular landscape painters to the present day. 'Seaport with the Embarkation of Saint Ursula' is a relatively rare example of foreground action in close-up, and for once the figures are at least as convincing as the whole which has something of the effect of a stage back-drop. This is the precise reverse of the case in the beautiful and mysterious 'Landscape with Psyche outside the Palace of Cupid', where it would be easy to conclude that Psyche's lonely plight might be explained by her having the shoul- ders and musculature of a heavyweight champion. Perhaps the boyish Cupid was simply intimidated? Meanwhile 'Landscape with Echo and Narcissus' brings us the first Page Three girl. Yet 'Landscape with Saint Philip baptising the Eunuch' shows Claudi- an land- and seascape at their beautiful best, together with the artist's mastery of a mysterious, silvery tonality. Such place and light never existed; this is a temporal Eden where cities and their vices awaited inven- tion still, or lay at the outer limits of the landscape where neither their smells — the artist was working in the 17th century nor dangerous attractions could pollute the pure country air.

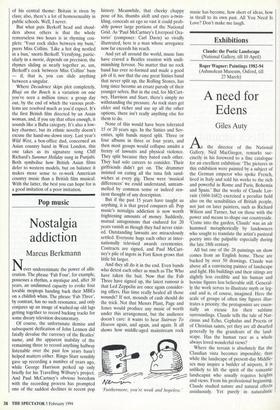

The advent of motorways brings Oxford within as rapid reach of west London as anywhere to the east of the City, and I am glad I followed an instinct to see the idiosyncratic but visionary paintings of Roger Wagner at the Ashmolean Museum. The catalogue suggests the artist continues to find more interest and relevance in Giorgione than Gilbert and George, a sen- timent with which I concur thoroughly. He takes elements directly from our real land- scape, East Anglian trees and cornfields, power stations and cooling towers, and turns them to the service of a new Chris- tian iconography. Many of his contempo- raries — he is nearly 37 — would deem such an approach morbid and fascist rather than moral and fascinating. The largest paintings are metaphysical — 'The Harvest is the End of the World and the Reapers are Angels' and 'Menorah' — and the for- mer is more moving, possibly because more poignant in its symbolism. There is also more panache in its making and it would lend itself readily as the basis of a tapestry for a major religious institution.

Wagner tackles the immense technical problems inherent in painting and drawing of this kind with a fair degree of success. He read English at university and had the fortune to study under the late Peter Greenham at the Royal Academy Schools. He needs continuing contact with first-class painters now to gain further mastery of his medium but his vision is complex and inter- esting already. Here is art and subject mat- ter which is about as unfashionable as it could be. That is why this unfashionable art critic made the journey to Oxford in the first place.

`The Harvest is the End of the World and the Reapers are Angels, 1989, oil on canvas, by Roger Wagner

Previous page

Previous page