ANOTHER EXODUS

The return of a million Soviet Jews to Israel is hailed as a miracle.

Ian Buruma considers its consequences Jerusalem THE Israeli airline El Al even flies them in on the Sabbath, from Warsaw, from Bucharest, from Berlin. Moscow at last is letting its Jews go, in ever increasing numbers: up to 45,000 people in Decem- ber, with more arriving every month. More than a million Soviet Jews have applied for immigration, or aliyah, to Israel. Abe Rosenthal, the former editor and current columnist of the New York Times, thinks this is a miracle over which we must rejoice. But then Abe Rosenthal doesn't have to live with the consequences.

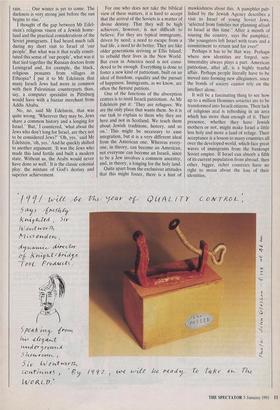

Natan Sharansky, the most famous Soviet immigrant in Israel, commented that 'what we will do now will influence the next 1,000 years of Jewish history'. Many Palestinians, afraid that the occupied terri- tories will be swamped by Jewish immig- rants, would agree. Sharansky warned that in six months half a million immigrants will be 'on the streets or in tents', which could easily result in 'civil war'. The Likud politician in charge of absorbing the im- migrants, Michael Kleiner, responded that it's about time to 'slaughter that sacred cow called Sharansky'.

A million new immigrants in a country of less than five million people puts the problems of other countries in some pers- pective. In Britain, for example, the pros- pect of taking in about 250,000 Hong Kong Chinese, most of whom speak English and all of whom are used to the capitalist ways of a British colony, is enough to elicit fears of race riots and the loss of national identity — both fears ripe for the political plucking. The Homo sovieticus, arriving in Israel without speaking Hebrew, and with no experience whatsoever of a capitalist society, will have much more trouble fit- ting in. Not only is there not enough housing — hence the Arab concern about settlements on the West Bank — but there are not enough jobs. More than half the Soviet immigrants are highly educated engineers, doctors and teachers. There is a joke going around that if a Soviet Jew doesn't come off the plane with a violin under his arm, he must be a pianist.

The fact that Israelis appear to be taking the whole thing in their stride 'demands respect, even if you fail to rejoice in the `miracle'. The whole thing might end up costing more than $30 billion, some of which will have to come from America, some from what is called the Diaspora, or Jewish well-wishers all over the world, and much of it from Israelis themselves. Politi- cians talk about `tightening belts' and appeal to Jewish idealism — always a trusted standby for those who ask for sacrifices.

The irony is that these Soviet ohm, or immigrants to the motherland, are the least idealistic in Jewish history. The pioneers, such as David Ben Gurion, were secular European Zionists, who wanted to build a socialist homeland peopled by Jewish idealists digging the earth and singing folk songs, their eyes fixed on the glorious collectivist future. It was in many ways the kind of rural dream typical of educated urbanites, who felt displaced in a hostile and fast-changing world. Zionism was an offshoot of 19th-century nationalism: the nation of Israel would give meaning as well as security. But it did not appeal to Orthodox Jews, who found enough mean- ing in the Torah, or to such religious thinkers as the German philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, who wrote that `the Jewish- ness of a Jew is done an injustice if it is put on the same level as his nationality'.

The European pioneers did not reckon, however, with a very different kind of Jew, from Yemen, Iraq or Tunisia, who saw Israel, so to speak, through Middle East- ern eyes. He was religious, impatient with the niceties of European-style parliamen- tarianism, and resentful of the disdain with which he was often treated by the Ashke- nazy elite. Such Jews, though fierce in their defence of the sacred Jewish land against the Arab enemies, were hardly good Zion- ists. Socialism and high European culture meant little to them. They voted for Begin and Shamir, who, though both of Polish origin, knew how to appeal to the' 'Orien- tal' Jews: Begin through a combination of courtliness and populism, Shamir by look- ing like a streetfighter — which at one time he was. Or they voted for the small, religious parties.

The Soviets, on the other hand, come from the same stock as the pioneers. They are the grandchildren of the early Zionists from Riga, Vilnius and Kiev; except for one thing: they loathe socialism and lack idealism. Nor are they Jewish patriots. Indeed, some say that many of them aren't even Jewish at all. The Absorption Minis- ter himself, Rabbi Yitzhak Peretz, recently said in Moscow that 30-40 per cent of the immigrants were non-Jewish, meaning that they have no Jewish mother, and show no inclination to convert to the Jewish faith.

I asked an Israeli working at a so-called Absorption Centre, near Jerusalem, about this. 'It is indeed a strange phenomenon in Jewish history,' he said, 'that all of a sudden people want to be Jewish.' If it is true that many Soviets are cooking up their ancestry, they are a little like the 'Deuts- chmark Germans' from Upper Silesia: any roots will do, as long as they get you out of the misery of economic catastrophe. Although this is a perfectly legitimate reason for emigrating, religious-minded Israelis worry about this. They believe it will have terrible consequences for the Israeli identity.

I was presented at the Absorption Cen- tre to a Soviet couple from Leningrad. Both spoke a little English, both were doctors, and both were definitely Jewish. They were called Meyerson, and they had arrived with their two young children. I asked them what had made them leave. They said that the Soviet Union had become a dangerous country, not just for Jews, but for everyone. Did they grow up with Jewish customs? Did they celebrate Jewish festivals? 'Oh, no', both said at the same time, `we are educated. We are doctors.' Did they encounter much discri- mination at their work? 'Well,' said Mrs Meyerson, 'maybe we didn't get promoted as much as we ought to have been. Other, stupid people had an easier time . . . But the Soviet Union is bad for everybody, a very dangerous country for our children.' Finally, I asked them what they thought of socialism. They both waved their hands dismissively. `All we want is to stand on our own two feet, to get jobs, a house. We want to live in peace and quiet.' The middle-aged lady from Long Island, who showed me around the Centre added: `Peace and quiet: just like all Israeli people.'

I got talking to the head of the Centre, Meier Edelstein. He was religious, and wore a kippa. Mr Edelstein saw the Soviet aliyah in biblical terms. `The new immigra- tion,' he said, `is the fulfilment of the vision of the prophets. Their vision was that Israel would be established again as our homeland and that Jews from all over the world would settle here.'

I asked him about the difficulties of resettling so many people. That, too, he saw in biblical terms: `Before our final redemption there will be many problems. There will be conflict among ourselves and threats to our security. Even the lack of rain. . . . Our winter is yet to come. The darkness is very strong just before the sun begins to rise.' I thought of the gap between Mr Edel- stein's religious vision of a Jewish home- land and the practical considerations of the Soviet immigrants. I had heard much talk during my short visit to Israel of 'our people'. But what was it that really consti- tuted this sense of 'our people', what was it that tied together the Russian doctors from Leningrad and, for example, the black, religious peasants from villages in Ethiopia? I put it to Mr Edelstein that many Israeli Jews had more in common with their Palestinian counterparts than, say, a computer specialist in Pittsburg would have with a bazaar merchant from Addis Ababa.

No, no, said Mr Edelstein, that was quite wrong. 'Wherever they may be, Jews share a common history and a longing for Israel.' But,' I countered, 'what about the Jews who don't long for Israel, are they not to be considered Jews?"0h, yes,' said Mr Edelstein, 'oh, yes.' And he quickly shifted to another argument. 'It was the Jews who made this land fertile and built a modern state. Without us, the Arabs would never have done so well.' It is the classic colonial ploy: the mixture of God's destiny and superior achievement. For one who does not take the biblical view of these matters, it is hard to accept that the arrival of the Soviets is a matter of divine destiny. That they will be high achievers, however, is not difficult to believe. For they are typical immigrants, driven by need; a need to escape from a bad life, a need to do better. They are like older generations arriving at Ellis Island, to rebuild their lives in the New World. But even in America need is not consi- dered to be enough. Everything is done to foster a new kind of patriotism, built on an ideal of freedom, equality and the pursuit of happiness. Immigrants, as we know, are often the fiercest patriots. One of the functions of the absorption centres is to instil Israeli patriotism. As Mr Edelstein put it: 'They are refugees. We are the only place that wants them. So it is our task to explain to them why they are here and not in Scotland. We teach them about Jewish traditions, history, and so on.' This might be necessary to ease integration, but it is a very different ideal from the American one. Whereas every- one, in theory, can become an American, not everyone can become an Israeli, since to be a Jew involves a common ancestry, and, in theory, a longing for the holy land. Quite apart from the exclusivist attitudes that this might foster, there is a hint of mawkishness about this. A pamphlet pub- lished by the Jewish Agency describes a visit to Israel of young Soviet Jews, `selected from families not planning aliyah to Israel at this time.' After a month of touring the country, says the pamphlet, `the youngsters left Israel with tears and a commitment to return and for ever!'

Perhaps it has to be that way. Perhaps where new identities are forged, sen- timentality always plays a part. American patriotism, after all, is a highly tearful affair. Perhaps people literally have to be moved into forming new allegiances, since the bonds of society cannot rely on the intellect alone.

It will be a fascinating thing to see how up to a million Homines sovietici are to be transformed into Israeli citizens. Their lack of religious zeal is refreshing in an area which has more than enough of it. Their presence, whether they have Jewish mothers or not, might make Israel a little less holy and more a land of refuge. Their acceptance is a lesson to many countries all over the developed world, which face great waves of immigrants from the bankrupt Soviet empire. If Israel can absorb a fifth of its current population from abroad, then other, bigger, richer countries have no right to moan about the loss of their identities.

Previous page

Previous page