Why she deserved to win

Christopher Booker

Four weeks ago, on the night the famous no-confidence debate launched us by one vote into this election, I scribbled down a guess as to the possible result. It read as follows: Conservatives 324 Labour 285 Liberals 7 Scot. Nats. 5 Welsh Nats. 1 Ulster Unionists 9 Others 4 Such a result would give the Tories an overall majority of 13 seats.

By the time most of you are reading these words, it will be evident either that I was on roughly the right lines, or that I was foolishly, hopelessly wrong. If the latter is the case, you had better turn instantly to the television column or some other more uplifting fare, since the remainder of this article will be written on the assumption that Mrs Thatcher will shortly be taking up residence at Number Ten, at least with a working majority, possibly with one rather larger than my original guess back in March.

Let us for once look on the bright side. It will have been right for Mrs Thatcher to be elected, if only because in the last three years, for all her faults and limitations, she has reflected a mood in the country which has run deeper than anything a tired, cautious, do-nothing Labour Party has any longer been able to represent. After the traumatic Heath-Wilson years of the mid Seventies, when finally everything seemed to be going wrong for Britain at once — with inflation, unemployment, trade union power and public spending all getting out of hand simultaneously — people have at least wanted to believe that there might be one last chance of breaking out from the shrinking circle of economic decline and overgovernment. They may not believe that readjusting the tax system will produce some miraculous industrial renaissance, or that axeing a few quangoes will halt the inexorable growth of bureaucracy. They may not hold out any enormous hope that Mrs Thatcher and her band of somewhat emasculated acolytes will suddenly display a Super-woman-like capacity to halt all the trends of national decline which have run so deep and so long that they are probably irreversible. But at least for a while there will be that modest lifting of the political spirits which follows from a complete change of ministerial landscape, and from the initial attempts to put into practice a new political philosophy, before they begin to run into the brick walls or quicksands of infeasibility.

While the honeymoon lasts, therefore, let us admit that British politics has not entirely lacked grounds for encouragement of late. For a start, it has been an enormous relief for the first time in thirteen years to go through an election without the choice of Prime Minister lying between Harold Wilson and Edward Heath — those two infinitely depressing legacies from the particularly nasty spasm of unreality through which English life passed in so many ways in the Sixties. We are at last beginning to move on from the worst of what those years stood for, socially and politically — all those neophiliac fantasies which produced massive redevelopment schemes in our cities, vast bureaucratic agglomerations in local government and the health service, decimal coinage, metrication, British Leyland and SO many other disasters. The age of Maplin, thank God, is behind us. The belief that we could bludgeon and blunder our way into some new technological, bureaucratic paradise by huge gestures and shadowy reforms breathed its last gasp with the long drawn-out fiasco of devolution.

Secondly, although the climate of those years affected both major parties equally, it is the Tory Party which has been able in opposition to move on more quickly and naturally to a new political task, taking account of at least some of the more obvious lessons learned from those unreal years. Nothing has been more obvious about the Labour Party as it has staggered through the last three years in government than that the collapse of Wilson-ism has left it almost completely bereft of any middle-of-theroad ideological driving force. For years the moderates of the Labour Party were able to hold out the hope that Socialism consisted of building more homes and hospitals, `comprehensiving' education, maybe taking the odd ailing industry into public ownership to promote investment and preserve jobs. Today those dreams have subsided into an almost complete blur of disillusionment, which is why Mr Callaghan's only real trump card in this election was that he was better able to 'get on with the unions' — and why the only real energy in the Labour Party in recent years has been on the extreme left, where alone it is still possible to dream wild dreams about tearing down the House of Lords and nationalising the banks to produce some misty Socialist millenium which, for most people, seems now further away than ever.

Thirdly, we should not underestimate the considerable psychological benefit to the nation of having been through that appalling trauma of the mid Seventies, from the moment when Edward Heath's credibility began to crack in 1972 to the 27 per cent inflation of the summer of 1975 and the great financial crisis of 1976. In those years we crept to the edge of the abyss — and despite the flurry of disorder in the past winter, it was an experience which few people really wish to go through again. Even the leaders of the major unions, by taking credit for having helped to reduce the inflation rate in 1975-8 by moderating wage demands, have implicitly admitted for the first time that runaway wages can play a substantial part in fuelling inflation — and it is a lesson the country will not be in a hurry entirely to forget.

In short we have passed, at least temporarily, into a quieter, less ambitious phase of politics, where few people have real hope that the future could be spectacularly better than the present, where all that most of us hope for is that somehow the show can be kept modestly on the road, without too much disorder, too much social chaos, without inflation getting once again completely out of hand, and without a recurrence of those premonitions of some far worse hell which have haunted us so often in the past seven years.

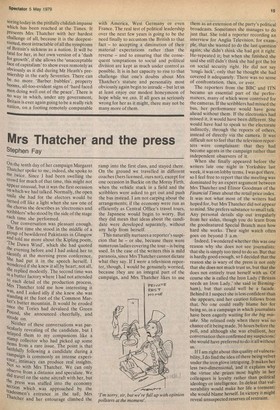

Clearly the worst immediate danger which confronts the new government, the one thing most likely to produce a renewal of those horrors, is the widespread persistence of what has perhaps in the Britain of the Seventies become the most unacceptable face of Socialism of all — that hidebound, even potentially violent belief which has infected so many groups in society that ultimately the world owes them a living, regardless of efficiency, public welfare or anything else. It is that utterly negative, soul-destroying, un-idealistic state. of mind which we saw two years ago behind much of the campaign against public spending cuts, which we saw rearing its head in the worst excesses of last winter, which we are seeing today in the pitifully childish impasse Which has been reached at the Times. It presents Mrs Thatcher with her hardest challenge of all, because it is the deepestrooted, most intractable of all the symptoms of Britain's sickness as a nation. It will be fatal for her, in her own version of a 'dash for growth', if she allows the 'unacceptable face of capitalism' to show even remotely as Obviously as it did during Mr Heath's premiership in the early Seventies. There can be no more 'Barber bubbles', property booms, all-too-evident signs of 'hard faced men doing well out of the peace'. There is no way in which, under any government, Britain is ever again going to be a really rich nation, on a footing remotely comparable with America, West Germany or even France. The real test of political leadership over the next few years is going to be the need finally to accustom the British to that fact — to accepting a diminution of their material expectations rather than the reverse — and to ensuring that the consequent temptations to social and political division are kept as much under control as possible. It is in her capacity to rise to that challenge that one's doubts about Mrs Thatcher's stature and personality most obviously again begin to intrude —but let us at least enjoy our modest honeymoon of hope while we can. If all goes as seriously wrong for her as it might, there may not be many more of them.

Previous page

Previous page