Exhibitions 1

Patrick Heron: Sydney Paintings and Gouaches 1989-1990 (Waddington Galleries, till 20 April)

Western approaches

Giles Auty

Anong a regrettably long list of tasks which sits on my desk awaiting urgent attention is that of writing a treatment for a book about St Ives and the artists who worked there from the mid-Thirties. I lived in west Cornwall myself for two spells each of about six years and have visited the area regularly before and since. This explains why, back in London, a surprising number of people think I am of Cornish origin. In fact, relatively few of the artists, writers and potters who lived and worked in west Cornwall over the years have been of local extraction, people born in the area prefer- ring, on the whole, to engage in more prac- tical careers such as mining, farming and fishing. The late Peter Lanyon was a rare exception to this rule, being born in St Ives in 1918. The artist died prematurely in a gliding accident in 1964, leaving an inter- esting body of work which is now attracting increasing critical attention.

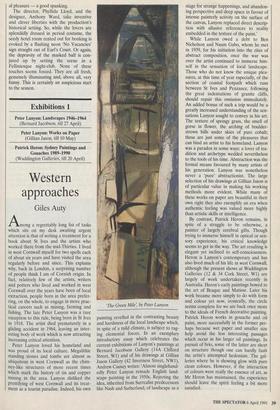

Peter Lanyon loved his homeland and was proud of its local culture. Megalithic standing stones and tombs are almost as ubiquitous in west Cornwall as the chim- ney-like structures of more recent times which mark the history of tin and copper mining in the area. Lanyon disliked the prettifying of west Cornwall and its treat- ment as a tourist paradise. Indeed, his own `The Green Mile; by Peter Lanyon painting revelled in the contrasting beauty and harshness of the local landscape which, in spite of a mild climate, is subject to rag- ing elemental forces. In an exemplary introductory essay which celebrates the current exhibitions of Lanyon's paintings at Bernard Jacobson Gallery (14A Clifford Street, W1) and of his drawings at Gillian Jason Gallery (42 Inverness Street, NW1), Andrew Causey writes: 'Almost singlehand- edly Peter Lanyon remade English land- scape painting in the 1950s. Rejecting the idea, inherited from Surrealist predecessors like Nash and Sutherland, of landscape as a stage for strange happenings, and abandon- ing perspective and deep space in favour of intense painterly activity on the surface of the canvas, Lanyon replaced direct descrip- tion with allusive references to reality embedded in the texture of the paint.'

While Lanyon owed a debt to Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo, whom he met in 1939, for his initiation into the rites of abstract composition, once the war was over the artist continued to immerse him- self in the sensation of local landscape. Those who do not know the unique plea- sures, at this time of year especially, of the section of coastal footpath which runs between St Ives and Penzance, following the great indentations of granite cliffs, should repair this omission immediately. An added bonus of such a trip would be a greatly increased understanding of the sen- sations Lanyon sought to convey in his art. The texture of springy grass, the smell of gorse in flower, the arching of boulder- strewn hills under skies of pure cobalt; these are just some of the pleasures that can bind an artist to his homeland. Lanyon was a paradox in some ways: a lover of tra- dition and archetype wedded nevertheless to the tools of his time. Abstraction was the formal means favoured by many artists of his generation. Lanyon was nonetheless never a 'pure' abstractionist. The large selection of his drawings at Gillian Jason is of particular value in making his working methods more evident. While many of these works on paper are beautiful in their own right they also exemplify an era when authentic feeling was valued more highly than artistic skills or intelligence.

By contrast, Patrick Heron remains, in spite of a struggle to be otherwise, a painter of largely cerebral gifts. Though trying to immerse himself in optical or sen- sory experience, his critical knowledge seems to get in the way. The art resulting is elegant yet inclined to self-consciousness. Heron is Lanyon's contemporary and has also lived much of his life in west Cornwall, although the present shows at Waddington Galleries (12 & 34 Cork Street, W1) are largely of work undertaken recently in Australia. Heron's early paintings bowed to the art of Braque and Matisse. Later his work became more simply to do with form and colour yet now, ironically, the circle seems complete for we are back once more to the ideals of French decorative painting. Patrick Heron works in gouache and oil paint, more successfully in the former per- haps because wet paper and smaller size help avoid the less interesting passages which occur in his larger oil paintings. In pursuit of brio, some of the latter are short on structure though one can hardly fault the artist's attempted hedonism. The gal- leries where he is showing glow with pure clean colours. However, if the interaction of colours were really the essence of art, as Mr Heron has maintained, the experience should leave the spirit feeling a bit more satisfied.

Previous page

Previous page