BOOKS

A figure of major minorness

Bevis Hillier

DON'T TELL SYBIL: AN INTIMATE MEMOIR OF E. L. T. MESENS by George Melly Heinemann, £17.99, pp. 226 Afew years back, when he was still with A. P. Watt and was my literary agent, Hilary Rubinstein gave me lunch at the Garrick Club. I told him that one day I wanted to write a book about the Elizabeth Canning scandal of 1753-54. Although she was only a London maidservant, Canning has an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography. The DNB bills her simply as `malefactor'; but no one knows if that is a fair description.

Canning claimed that on New Year's Day 1753 she was abducted by two ruffians in the City of London and carried off in a coach to a brothel in Enfield, where she refused to become a prostitute. She said a gipsy had cut off her stays and that she had been imprisoned for almost a month in an attic, from which she eventually escaped. The gipsy was condemned to death for stealing the stays, worth 10 shillings, but received a royal pardon in the nick of time by insisting that she had been in Dorset at the time of the alleged theft, and had wit- nesses to prove it. So then Canning was tried for perjury, was convicted and sen- tenced to be transported to America, where she married a great-nephew of a governor of Connecticut.

In 1753-54 the whole of Britain took sides on the Canning case, as if in a civil war. But to this day no one knows who was telling the truth — Canning, the gipsy, or neither. Trying to sell my idea to Rubin- stein, I pointed out that the case had involved great figures. Henry Fielding, the novelist, had ruled on the matter as a mag- istrate. He had written a pamphlet on the case. So had Voltaire, the painter Allan Ramsay and the Lord Mayor of London. Josephine Tey turned it into fiction (in modern dress) in The Franchise Affair. And six non-fiction books have been devoted to it in this century, none of which satisfac- torily solves the mystery.

Rubinstein listened attentively, with the aid of a large brandy. Then he said:

Bevis, if I were to stand on this table and shout 'Jack the Ripper!' every single person here would know who I meant. But if I shouted 'Elizabeth Canning!', who do you think would have heard of her?

As a matter of fact, Brian Masters, sitting at the long table that day, knows about Canning and has mentioned her in a preface about Voltaire; and a Garrick barrister later told me he had cited the case in one of his addresses to a jury. But of course I saw Rubinstein's point. Canning is not sure-fire box-office.

The same could be said of E. L. T. Mesens, a member of the Surrealists. If you stood on a Garrick table and bawled `Dali!, Magritte!' (a pretty surreal act) you'd be unlikely to find a member who hadn't heard of them — I can't vouch for the Carlton Club. But Mesens? He stands in relation to the famous Surrealists rather as Edward Upward does to the Auden- Isherwood-Day-Lewis-MacNeice group: the one it is quite chic even to have heard of Those who have heard of Mesens are likely to have done so from George Melly, who for years has gently plugged him in broad- casts, articles and his autobiography.

There was just a suspicion in my mind that Mesens might be a sustained practical joke like the 'Bruno Hat' art exhibition staged by Brian Howard and Evelyn Waugh. (I have always had the same nag- ging doubt about Sir Edmund Backhouse, the subject of Hugh Trevor-Roper's classic biography A Hidden Life — was he a fig- ment? I'm still not sure.) Mesens — an anagram of semens — is just the sort of name that might be concocted by Melly, who recalls in this book that the two main things he learned in the Royal Navy were `how to pipe an admiral aboard and how to wank in a hammock without waking up the whole mess-deck'. After reading this book I believe in Mesens. He cannot, perhaps, be added to the short list of famous Belgians which includes King Leopold, Magritte, Delvaux, James Ensor and Hercule Poirot; but the fact that three of these were artists of a surreal tendency owes much to his proselytising on their behalf. He was, like Apollinaire and Cocteau for the Cubists, a formidable propagandist.

He was an early friend of Magritte and helped build his reputation. So to some extent our interest in Mesens will depend on how much we value Magritte. To me, Magritte is not much more than a visual jokesmith. What he achieved in paint was comparable to what the Goons and Monty Python achieved with words — admittedly, he got there first. His champions, such as David Sylvester and Melly, place him much higher: on a level, say, with Lewis Carroll, that prototype Surrealist. But his technique was crude, his imagination unsubtle, com- pared (in both aspects) with Dali at his best. The defenders of Magritte argue that he had more integrity than Dali. Well, Mahatma Gandhi had more integrity than the two of them put together, but that does not make him a great artist.

A typical Magritte conceit, if you'll for- give the jingle, is the mermaid whose top half is a fish's head and bottom half the legs of a woman. Well, ho, ho, ho. A wan smile is brought to one's lips by the rather obvious role-reversal (sole-reversal? cod work of art? high gudgeon? the dace that launched a thousand ships? one hesitates to carp? hook, line and stinker? have you ever seen a bream walking? — Surrealists do not have a monopoly of silly jokes.) Or there is his stupid painting of a pipe, inscribed, `Ceci n'est pas une pipe'. Okay, a gauche art-philosophy point is being made (it would take a moron to miss it); but the aesthetic value of this work is virtually nil. Who would want the bloody thing on his wall? It would be like hearing the same substandard joke endlessly repeated by a pub bore. In a recent article on Mesens in the Independent on Sunday, David Sylvester marvelled that

Till almost the end of Magritte's life in 1967, collectors of modern pictures, and the experts they listened to, thought he was just an illustrator of amusing paradoxes and wheezes.

I think those experts were right.

Not reckoning Magritte much rather dampens one's ardour for Mesens. The person who despises Hitler is unlikely to join a fan-club for Goebbels. Mesens' philosophy of life was as uncouth as Magritte's art; and it was this that initially attracted the schoolboy George Melly — `Permanent revolt . . . was amongst [Surre- alism's] most inflexible principles.' You can see the appeal of that for a public school- boy in the 1940s. I'm all in favour of revolt- ing if there's something that deserves to be revolted against; but revolt for revolt's sake is capricious and often cruel. And some of the Surrealists' rebellions were just plain philistine. Melly tells us how Mesens humoured 'the Parisian Surrealists who dis- missed music, with the authority of an essay by De Chirico, as a stupid and mean- ingless art'. So much for Bach and Mozart, not to mention old George himself belting out, `I've got Ford-engine movements in my hips — ten thousand miles guaranteed.'

Mesens' attitude was all the more per- verse in that he had been a composer when he was young. Born in 1903, he had met Erik Satie in the early 1920s. With Satie's encouragement, he set several poems to music, Man Ray designed the cover of his setting of 'Garage' by Philippe Soupault. Mesens gave up music in 1923, but wrote poetry and was increasingly attracted by the visual arts, especially by the work of Magritte, whom he first met in 1920. The two men became friends. Of course they eventually quarrelled. With Surrealism as with religious cults — cabals and excom- munications were all part of the fun. He edited little reviews. He was a minor artist, creating works with such epater le bourgeois titles as 'Starry Violin Giving Birth to a Pointillist Child'. He organised art exhibi- tions. In the late 1930s he began to spend more time in London 'until he was, to all extents and purposes, a resident if not a cit- izen'.

In 1938 he became director of the Lon- don Gallery in Cork Street, exhibiting works by John Piper before, as Melly puts it, Piper became 'a sugar-coated topogra- pher'. In the war Mesens made BBC broadcasts to Belgium. After it, he set up a new gallery in Brook Street, with some financial top-up from his wife — the Sybil of this book's title — who became chief buyer at Dickins & Jones. There Melly worked for him, learning how to hang an exhibition. (Referring to picture shapes rather than subjects, he writes, 'A portrait should always be flanked by two landscapes and vice versa.') Like many of the paintings he bought and sold, Mesens was a nasty piece of work. Melly heroically managed to stay his friend till the end, but he does not gloss over his less savoury attributes: his cantan- kerousness and venomous quarrels; his subterfuges: 'Don't tell Sybil', his frequent plea to Melly, suggests Billy Bunter's 'Not a word to Bessie!' — his gross sister — when a tuckbox arrived; and there was something very Bunterian about Mesens in his dodges and wheezes and his howls of indignation when exposed or punished. He was a penny-pincher, expecting Melly to tie up parcels containing expensive paintings with old bits of string, carefully saved. He was a bully. He was financially devious. And hav- ing promised Melly a Magritte, he kept him waiting for years, finally giving him a sec- ond-division work.

Why should we want to learn about this not very pleasant person and his dubious contribution to art history? The answer is, this is a sort of Johnson's 'Life of Boswell'. Melly and Mesens make a great double act. One Sunday the double act became a triple act when Mesens and Sybil invited Melly to join them in a spot of sexual troilism, Mesens was catholic in his sexual tastes. He had an affair with the art collector Peggy Guggenheim, who called him 'Mittens'. That was one of the things Sybil was not to be told. And for a time Melly was his Bosie as well as his Bozzy: I was always fascinated to see how, before we started, he would squeeze the end of my dick while watching closely. I presume his object was to make sure there was no discharge, a trick I imagine he had learnt from the Flem- ish whores of his youth.

When Melly and Mesens went into a Soho brothel, the elderly prostitute wrongly assumed they were gays looking for a room.

Of the two men, Melly is much the more interesting and loveable; and luckily we get just as big a helping of him as of Mesens. Unlike his friend, he needs no introduc- tion. If confession is good for the soul, his soul must be in very good nick, we know so much about him. Disraeli's wife could never remember which came first, the Romans or the Greeks; and I can never remember whether it was Melly who seduced Sir Peregrine Worsthorne on the sofa at Stowe, or vice versa. The ur-text on Melly is an interview with the Listener of 1969. Asked what had caused him to turn from homosexuality to heterosexuality, he replied, 'Girls saying yes.' I've always thought that Girls Saying Yes should have been a Kingsley Amis novel.

When I used to lunch with Mark Boxer at Chez Victor, he would dart away to the telephone to receive from Melly ideas for his next cartoon. He told me that at parties Melly had to be restrained from tearing off all his clothes and imitating, in turn, 'man, woman, and dog'. I met Melly only once on a radio critics' programme just after I had reviewed his book Revolt into Style. The review had been cut by the paper's then literary editor, and unfortunately he had cut the friendlier parts of the notice, leaving my reservations. When I explained this to Melly, there was a prolonged pause. Then he beamed and said, 'Horrid old liter- ary editor!' It was beautifully played, leav- ing me in doubt as to whether (a) he believed me (b) he was cross anyway.

We are all familiar with the roly-poly fig- ure in giant fedora and primary-coloured suits, who gives an opinion on Turner Prize entries, often accompanied by Maggi Ram- bling, scattering fag-ends in her wake like a machine-gun spitting out spent bullets. No programme on Surrealism is complete without him. He bobbed up again in a recent two-parter on Dali, whom he called `a swine'. Swanning into view in Paris to point out one of the sci-fi Metro entrances by Hector Guimard which fascinated Dali, he gestured at a nearby awning. It was bla- zoned `Cafe Dali'. Melly's eyes gleamed. `Ah, the "certainty of chance". That's a very surrealist idea.' Again the phrase comes into this book — three times.

Then there is his other life as a musician. He is always on hand to chat on television about newly deceased jazz trumpeters, whom invariably he has known. The last trump will probably be followed by a short piece to camera by Melly. He is a sort of vaudeville Renaissance Man, and it would be hard to find somebody who dislikes him.

Beyond all these talents, and superior to them, is his skill as a raconteur, honed in a thousand bars and nightclubs. The book effervesces with wit and stylish language. When Magritte falls in love with an 11- year-old girl seen on a roundabout at a fair in Charleroi, she is 'this Lolita of the carousel'. Like most Continentals, Mesens cannot pronounce `th'; Melly finds it hard not to giggle when Mesens begs him to 'kiss me on ze mouse'. The connoisseur Douglas Cooper is this brilliant and odious figure who I suspect still haunts the nightmares of ageing cura- tors, art historians and German airmen.

Again on Cooper:

I had the feeling that, if pricked by a fork, he would have spurted like chicken Kiev, but bile instead of butter.

Having a bet in a Belgian casino, Melly thinks he is 'about to become the man who broke the bank at Knokke Le Zoute Albert Plage'. Visiting Magritte's house, he notes `the neat chiropodist-like bell of that bour- geois villa in La Rue de Mimosas'. And, on his central subject: 'There was a strong ele- ment of Volpone in E. L T Mesens.'

Like Trevor-Roper in A Hidden Life, Melly establishes a figure of major minor- ness and makes the sordid enchanting for us. The circle he describes — particularly because odd aristos flit in and out of the story, and little magazines are founded and fold — reminds one of the cast of an Anthony Powell novel. Even the names are Powellesque:

Amongst those present, Ithell Colquhoun had refused to relinquish her interest in the occult, and resigned rather than break her wand. .. That strange couple, Dr Grace Pailthorpe and her much younger lover, Reuben Mednikoff, were barred for almost the opposite reason. . . Tony del Renzio was an enthusiastic volunteer who had published a surrealist manifesto called Arson in 1942...

Melly knows how to pile on the comedy until we are reduced to helpless laughter. Just one example. He is working at the Brook Street gallery. He and Mesens spy, on the opposite pavement, a rather pompous-looking man. An expensive lug- gage shop is about to open. The proprietor is irritably directing a young woman in the window as to how the gold and pig-skin suitcases should be displayed. Mesens, with his surrealist talent for practical jokery, suggests that Melly should cross the road, tap the man on the shoulder and, when he turns round, deliver the following formal speech: 'The managing director of the Lon- don Gallery opposite has asked me on his behalf to wish you good luck, sir.'

He will thank you no doubt in a perfunctory way,' said Edouard [Mesens]. 'But then, after a few minutes, repeat the formula, good luck, sir, and continue to shout it louder and loud- er — GOOD LUCK, SIR! GOOD LUCK, SIR! GOOD LUCK, SIR! —until he becomes mad with rage.' So while Edouard watched from behind the Picabia in the window I carried out his sug- gestions to the letter. It worked like a dream. Puzzled irritation (`Yes, yes, yes') was soon replaced by total hysteria. 'I shall call the police!' the man yelled, shaking his fist at me. . . It was perhaps a shame he didn't fulfil his threat.

`And what is the charge, sir?' 'He wished me good luck.' `Sir?'

Though Melly is severe on Mesens' betis- es, you feel he is always a counsel for the defence. Like Christopher Isherwood when transmuting the ghastly Gerald Hamilton into 'Mr Norris', he deploys a redemptive humour. And even when he finds it hard to laugh, he mitigates and forgives — perhaps under the Old Pals' Act, perhaps on the principle tout comprendre c'est tout pardon- neri or perhaps by the good old surrealist maxim that it doesn't matter what you say, true or false, as long as it is the first thing that pops into your head. When Dali's fel- low Surrealists accused him of glorifying Hitler in one of his paintings, he said, 'But this is-how Hitler appeared in my dreams! So how else could I paint him?'

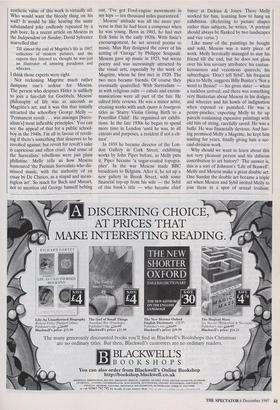

Previous page

Previous page