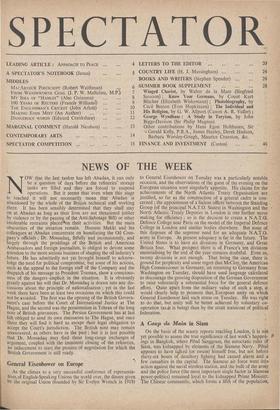

A Coup de Main in Siam On the basis of

the scanty reports reaching London, it is not yet possible to assess the true significance of last week's happen- 0 ings in Bangkok, where Pibul Sanggram, the autocratic ruler of Siam, was kidnapped by elements of the Siamese Navy. Pibul appears to have tallked (or swum) himself free, but not before thirty-six hours of desultory fighting had caused alarm and a few casualties in the capital. The Siamese air force went into action against the naval wireless station, and the bulk of the army and the police force (the most important single factor in Sia,mese power-politics) remained loyal to the kidnapped Prime Minister. The Chinese community, which forms a fifth of the population. and has been partially penetrated by the Communists, was not involved, and ideological issues seem to have been absent from an essentially domestic fracas. Coups d'etat have long formed part of the political climate of Siam, and this abortive attempt at one was presumably organised by the Prime Minister's numerous enemies, exploiting the discontent which has been growing in the Navy since the Government decided' to transfer control of the Customs and Excise from that service to the police. The out- come of the whole affair may well be to strengthen the position of Pibul's administration, which—although, like most modern Siamese Governments, corrupt and repressive—has aligned itself with the West in opposition to Asiatic Communism.

Previous page

Previous page