FACT, FICTION AND THE ROYAL RATS

Henry Porter exposes the working methods

of the tabloids' royal correspondents, and accuses them of undermining the monarchy

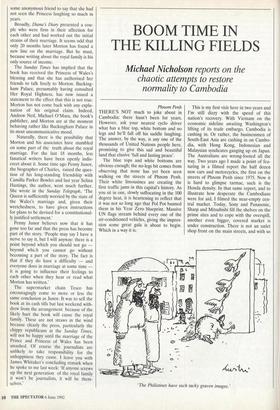

FOR THE first time, the royal family is seriously threatened by the activities of the press. Rupert Murdoch's Sunday Times is about to publish extracts from a book Diana: Her True Story — by Andrew Mor- ton, the former royal correspondent of the Daily Star and News of the World, which according to the cleverly engineered pre- publicity makes damaging allegations about the state of the Prince and Princess of Wales's marriage. Morton, so the publicity goes, claims that the Princess of Wales once attempted to commit suicide and that there exists a distance between the royal couple which is tantamount to a separation. Morton apparently implies that the Prince is close to other women besides his wife.

In one sense the precise details of what he has written do not much matter, because Morton and the republican-mind- ed Sunday Times are merely building on the hints and nudges that have appeared in other popular newspapers over the last two or three years. Very slowly, the taboos surrounding what journalists feel able to say about the family have been eroded, so we reach a state where the royal establish- ' ment is very anxious about what this tabloid journalist is about to publish.

The Sunday Times, which has paid between £240,000 and £275,000 for the serialisation rights of the book it has renamed 'Diana, Her Own Story', can in practice say anything it wants about the Prince and Princess of Wales because (as is well known) the royal family feel unable to defend themselves by suing for libel. The standards of accuracy and fairness are therefoie necessarily less demanding than in any other story. It is perhaps worth remembering that if damaging accusations were made about any other individual's pri- vate life they would almost certainly sue, as indeed the editor of the Sunday Times, Andrew Neil, amply demonstrated three years ago in the wake of the Pamella Bor- des affair.

Ever since the national press appointed specialist reporters to watch the royal fami- ly it has been inevitable that newspapers would pursue this particular story. After the royal couple's courtship, their wedding and the birth of their children, there is lit- tle else which will interest this highly paid and highly motivated group of reporters. Pursuit of it justifies their salaries, expense accounts and their status in newspaper offices. If the Sunday Times and Andrew Morton do not go as far• as their publicity predicts, the assault on the marriage will continue, fuelled as it is by the urgent demands of newspaper competition and the considerable ingenuity of the rat pack.

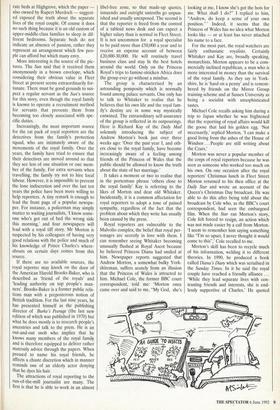

Royal reporting emerged as a speciality in the middle Seventies, when Prince Charles was looking for a bride. As the Queen's children grew up and found spous- es, so the newspapers spent more money on specialist teams of reporters and pho- tographers to follow them. Resourceful journalists were attracted to the curious speciality. Over the years they have includ- ed Harry Arnold for the Sun (now Daily Mirror), Ashley Walton of the Daily Express, Richard Kay of the Daily Mail, and Andrew Morton himself. The acknowl- edged dean of the group is a ruddy-faced man in his fifties, James Whitaker of the Daily Mirror, who bosses his colleagues in the manner of someone arranging the beat- ers on a shoot. He is a popular man who is surprisingly sensitive about his reputation. When I talked to him for this article he said, 'You're going to be supercilious about us, aren't you?'

Whitaker and his colleagues are highly organised, and much of the time co-oper- ate on the story in hand. For instance, if the Princess of Wales is staying at High- grove all gates to the estate will be covered by the press, who then relay her move- ments to each other by telephone, or some- times short-wave radio. They were the first group of reporters to use cell phones and satellite transmission of pictures and sto- ries. For much of the time they pool infor- mation. So, instead of half a dozen reporters lurking to catch the words of a member of the royal family,-one member of the cartel will report back to the others. It is a matter of pride to Harry Arnold that, when he heard the Duke of Edinburgh utter the famous `slitty-eyed' remark on a royal visit to China, he told his colleagues, all of whom used the story.

Their sources are usually at the servant level in Buckingham Palace and on the royal yacht. Newspapers are sometimes approached independently by royal employees who want to sell indiscretions. Last year, for instance, a member of Britan- nia's crew went round Fleet Street touting a story which was eventually used by the Sun. But more often the information is gleaned by the reporters who cultivate footmen and housemaids.

Two years ago, Morton made a number of 'disclosures' about the Prince and Princess's separate sleeping arrangements. At the time, the information was believed to have come from a disloyal footman. A similar story appeared on the Sun's front page this week with pictures showing sepa-

rate beds at Highgrove, which the paper also owned by Rupert Murdoch — suggest- ed exposed the truth about the separate lives of the royal couple. Of course it does no such thing because it is an old custom of upper-middle-class families to sleep in dif- ferent bedrooms. Separate beds do not indicate an absence of passion, rather they represent an arrangement which few peo- ple can afford but which many envy.

More interesting is the source of the pic- tures. The Sun said that it received them

anonymously in a brown envelope, which considering their obvious value in Fleet Street at present seems extraordinarily for- tunate. There must be good grounds to sus-

pect a regular servant as the Sun's source for this story, even though the royal family

is known to operate a recruitment method for servants that prevents them from becoming too closely associated with spe- cific duties.

Increasingly, the most important source for the rat pack of royal reporters are the detectives from the family's protection squad, who are intimately aware of the movements of the royal family. Over the years, the family have tried to ensure that their detectives are moved around so that they see less of one situation or one mem- ber of the family. For extra servants when travelling, the family try not to hire local labour. However, it is impossible to prevent the lone indiscretion and over the last ten years the police have been more willing to help reporters. A tiny remark is enough to lead the front page of a popular newspa- per. For instance, a policeman may simply mutter to waiting journalists, 'I know some- one who's got out of bed the wrong side this morning,' and four newspapers will lead with a royal tiff story. Mr Morton is suspected by his colleagues of having very good relations with the police and much of his knowledge of Prince Charles's where- abouts on certain days comes from this source.

If there are no available sources, the royal reporter may knock on the door of the American Harold Brooks-Baker, who is described as 'friend of the royals' and 'leading authority on top people's man- ners'. Brooks-Baker is a former public rela- tions map with a preposterous notion of British tradition. For the last nine years, he has presented himself as the publishing

director of Burke's Peerage (the last new edition of which was published in 1970) but

what he does mostly is to research people's ancestries and talk to the press. He is an out-and-out snob who implies that he knows many members of the royal family and is therefore equipped to deliver rather matronly advice through the papers. When pressed to name his royal friends, he affects a chaste discretion which in manner reminds one of an elderly actor denying that he dyes his hair.

The attractions of royal reporting to the run-of-the-mill journalist are many. The first is that he is able to work in an almost libel-free zone, so that made-up quotes, innuendo and outright untruths go unpun- ished and usually unexposed. The second is that the reporter is freed from the control of a tabloid news desk and can expect a higher salary than is normal in Fleet Street. It is not uncommon for a royal specialist to be paid more than £50,000 a year and to receive an expense account of between £20,000-30,000. He will routinely travel business class and stay In the best hotels around the world. Only on the Princess Royal's trips to famine-stricken Africa does the group ever go without a minibar.

The group is characterised by an astounding pomposity which is normally found among palace servants. One only has to talk to Whitaker to realise that he believes that his own life and the royal fam- ily's destiny are in some way mystically entwined. The extraordinary self-assurance of the group is reflected in its outpourings. Here is Richard Kay of the Daily Mail solemnly introducing the subject of Andrew Morton's book just over three weeks ago: 'Over the past year I, and oth- ers close to the royal family, have become increasingly aware of a feeling among friends of the Princess of Wales that the public should be allowed to know the truth about the state of her marriage.'

It takes a moment or two to realise that in the portentous phrase 'others close to the royal family' Kay is referring to the likes of Morton and dear old Whitaker. Incidentally, it is a common affectation for royal reporters to adopt a tone of pained sympathy, regardless of the fact that the problem about which they write has usually been caused by the press.

Royal reporters are vulnerable to the Malvolio complex, the belief that royal per- sonages are secretly in love with them. I can remember seeing Whitaker becoming unusually flushed at Royal Ascot because he believed Princess Diana had smiled at him. Newspaper reports suggested that Andrew Morton, a somewhat bulky York- shireman, suffers acutely from an illusion that the Princess of Wales is attracted to him. Michael Cole, the former BBC court correspondent, told me: 'Morton once came over and said to me, "My God, she's looking at me, I know she's got the hots for me. What shall I do?" I replied to him, "Andrew, do keep a sense of your own position."' Indeed, it seems that the Princess of Wales has no idea what Morton looks like — or at least has never attached his name to a face.

For the most part, the royal watchers are fairly enthusiatic royalists. Certainly Whitaker and Kay are, broadly speaking, monarchists. Morton appears to be a com- mercially inclined republican, a man who is more interested in money than the survival of the royal family. As they say in York- shire, he is 'hard on a penny' and is remem- bered by friends on the Mirror Group training scheme and at Sussex University as being a socialist with unsophisticated tastes.

Michael Cole recalls asking him during a trip to Japan whether he was frightened that the reporting of royal affairs would kill the goose that laid his golden egg. 'Not necessarily,' replied Morton, 'I can make a good living from the ashes of the House of Windsor ... People are still writing about the Czars.'

Morton was never a popular member of the corps of royal reporters because he was seen as someone who worked too much on his own. On one occasion after the royal reporters' Christmas lunch in Fleet Street Morton returned to his then office at the Daily Star and wrote an account of the Queen's Christmas Day broadcast. He was able to do this after being told about the broadcast by Cole who, as the BBC's court correspondent, had seen the embargoed film. When the Star ran Morton's story, Cole felt forced to resign, an action which was not made easier by a call from Morton. 'I seem to remember him saying something like "I'm so upset, I never thought it would come to this",' Cole recalled to me.

Morton's skill has been to recycle much of his information, welding it to different theories. In 1990, he produced a book called Diana's Diary which was serialised in the Sunday Times. In it he said the royal couple have reached a friendly alliance ... 'While they lead separate lives with con- trasting friends and interests, she is end- lessly supportive of Charles.' He quoted

some anonymous friend to say that she had not seen the Princess laughing so much in years.

Broadly, Diana's Diary presented a cou- ple who were firm in their affection for each other and had worked out the initial strains of their marriage. It seems odd that only 20 months later Morton has found a new line on the marriage. But he must, because writing about the royal family is his only source of income.

The Sunday Times has implied that the

book has received the Princess of Wales's blessing and that she has authorised her friends to talk freely to Morton. Bucking- ham Palace, presumably having consulted Her Royal Highness, has now issued a statement to the effect that this is not true.

Morton has not come back with any expla- nation of his • original claim. Indeed, Andrew Neil, Michael O'Mara, the book's publisher, and Morton are at the moment behaving rather like Buckingham Palace in its most uncommunicative mood.

Naturally, there is the possibility that Morton and his associates have stumbled on some part of the truth about the royal marriage. For the last 18 months, less fanatical writers have been openly indis- creet about it. Some time ago Penny Junor, the biographer of Charles, raised the ques- tion of his long-standing friendship with Camilla Parker Bowles and last year Selina

Hastings, the author, went much further. She wrote in the Sunday Telegraph, The

Queen is sufficiently worried by the state of the Wales's marriage and, given their wretchedness, to have given instructions for plans to be devised for a constitutional- ly justified settlement.'

Penny Junor believes now that it has gone too far and that the press has become part of the story. 'People may say I have a nerve to say it, but I will anyway: there is a point beyond which you should not go , beyond which you cannot go without becoming a part of the story. The fact is that if they do have a difficulty — and everyone does in marriage at some time it is going to influence their feelings to each other when they hear or read what Morton has written.'

The supermarket chain Tesco has encouragingly come to more or less the same conclusion as Junor. It was to sell the book at its cash tills but last weekend with- drew from the arrangement because of the likely hurt the book will cause the royal family. These are not straws in the wind because clearly the press, particularly the

chippy republicans at the Sunday Times,

will not be happy until the marriage of the Prince and Princess of Wales has been smashed. Of course the journalists are unlikely to take responsibility for the unhappiness they cause. I leave you with James Whitaker's concluding remark when he spoke to me last week: 'If anyone screws up the next generation of the royal family it won't be journalists, it will be them- selves.'

Previous page

Previous page