BOOM TIME IN THE KILLING FIELDS

Michael Nicholson reports on the chaotic attempts to restore normality to Cambodia

Phnom Penh THERE'S NOT much to joke about in Cambodia: there hasn't been for years. However, ask your nearest cyclo driver what has a blue top, white bottom and no legs and he'll fall off his saddle laughing. The answer, by the way, is any one of the thousands of United Nations people here, promising to give this sad and beautiful land that elusive 'full and lasting peace'.

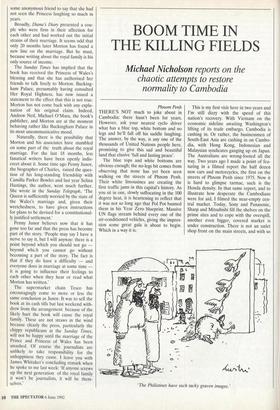

The blue tops and white bottoms are obvious enough; the no-legs bit comes from observing that none has yet been seen walking on the streets of Phnom Penh. Their white limousines are creating the first traffic jams in this capital's history. As you sit in one, slowly suffocating in the 100 degree heat, it is heartening to reflect that it was not so long ago that Pol Pot banned them in his Year Zero blueprint. Massive UN flags stream behind every one of the air-conditioned vehicles, giving the impres- sion some great gala is about to begin. Which in a way it is.. This is my first visit here in two years and I'm still dizzy with the speed of this nation's recovery. With Vietnam on the economic sideline awaiting Washington's lifting of its trade embargo, Cambodia is cashing in. Or rather, the businessmen of South-East Asia are cashing in on Cambo- dia, with Hong Kong, Indonesian and Malaysian syndicates ganging up on Japan. The Australians are wrong-footed all the way. Two years ago I made a point of fea- turing in a filmed report the half dozen new cars and motorcycles, the first on the streets of Phnom Penh since 1975. Now it is hard to glimpse tarmac, such is the Honda density. In that same report, and to illustrate how desperate the Cambodians were for aid, I filmed the near-empty cen- tral market. Today, Sony and Panasonic, Sharp and Mitsubishi fill the shelves on the prime sites and to cope with the overspill, another even bigger, covered market is under construction. There is not an unlet shop front on the main streets, and with so

The Philistines have such tacky graven images.'

many foreign companies looking for space property prices are out of control. Two years ago we slept under tattered mosquito nets in the squalid rooms of the Monorom Hotel, with a splendid view of the rats bur- rowing into the garbage pyramid below. Now it's $170 a night, breakfast extra, at the luxurious Cambodiana built in the image and shadow of Prince Sihanouk's royal palace on the banks of the Mekong. And to take the overflow (and with so much of the Cambodiana, given over to the UN there's a lot of that) a Thai company has just opened an even more opulent floating hotel next door. Name it and it's booming here, including prostitution mostly Vietnamese girls whose mothers learnt their trade massaging the war-weary GIs just across the border in Saigon.

What a shame, then, if the Legless Blue and Whites botch it up, as they very well might.

This is the biggest, costliest operation the UN has ever attempted, a tandem civil and military administration to restore some order in the wake of Pol Pot's bloody shambles. It goes by the ugly acronym Untac, United Nations Transitional Authority, Cambodia — which should spell salvation. Its job is to implement last Octo- ber's peace accord in Paris, where the war- ring factions — principally, the Vietnamese-backed government of Hun Sen and the Khmer Rouge — agreed to a ceasefire and an interim coalition (Supreme National Council) leading to UN-supervised elections next April and May. By that time Untac is pledged to dis- arm almost half a million soldiers and re- settle over 350,000 refugees. All this in a country that has no experience of democra- cy, where roads, main bridges and tele- phone communication hardly exist and where mines have made much of the land uninhabitable. As Yasushi Akashi, Untac's civil head, said recently, 'If I was a masochist, I could not hope for more!'

It is a schedule that most observers, as well as many among the UN here, consider quite unachievable. It is already running late and, worse, the big-hearted promises made by so many countries have yet to materialise in Phnom Penh. Of 20,000 sol- diers and .officials who should have arrived,

only about 6,000 have turned up. Untac was promised $3 billion. Only about 400 million — some say only 200 million -

have been received to date. To Untac's credit, the ceasefire, save for a few mortar exchanges mid-country, is holding. Six months ago, nobody would have bet on that. But if the missing money, soldiers and officials are not provided soon, Untac would be advised to leave before the blood- letting begins again.

Consider the armies. They have to be dismantled and their weapons and troops surrendered to UN cantonments by the beginning of July. After that the rains come and movement over much of the country is impossible. The timetable is as tight as that, yet only in the past few weeks have small contingents of UN troops gone into the hostile zones to begin looking for suit- able cantonment sites. If the armies cannot be demobilised before the rains, the peace process could be washed away.

Consider the refugees. There is no point in promising elections if such a high per- centage of voters are still in camps in Thai- land. Untac, with the additional help of UN High Commission for Refugees, says it must have them back and resettled by December. Less than seven months to bring those 350,000 home. That is over 11,000 a week. Recently I filmed the first train-load being brought to Phnom Penh from Battambang, the nearest large town to the Thai border. There were only 700 people on board. To clear the human log- jam by their own Christmas deadline, Untac would need 10 trains a week. There are not that many trains in the entire coun- try.

Consider the mines. Cambodia is the world's biggest minefield. They talk here about millions of mines. There are an esti- mated 30,000 registered amputees from this 17-year-old civil war, and since peace broke out there have been 300 new ones every month. The risk of inviting people away from the safe camps of Thailand to the minefields of home worries Untac and UNHCR alike. Yet the only mine clear- ance currently underway is being done by three British volunteers belonging to the Halo Trust, a charity led by Colonel Colin 'Mad Mitch' Mitchell. We spent a day with Mike Croll, a former Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal Captain, who was clearing villages close to the Thai border. He and his small team of Cambodian volunteers found and blew up 11 mines, nine of them in one man's backyard. It can sometimes take an entire working day, dawn till dusk, to detect and clear an area ten yards by two. (If you care to, work out how long it would take at that rate to clear the most intensive minefield, that stretches 100 miles between Pailin and Pursat.) The Halo Trust is desperately short of funds, so it would seem that Cambodia's entire mine clearance programme presently depends on Halo's Bank of Scotland overdraft. The UN has its own instructors from many nations — India, Britain, Holland, France, New Zealand — under the command of an affable Royal Engineer Colonel, but many more Cambodians will lose their feet and legs or both, or worse, before their Cambo- dian trainees are out there in the fields detecting. The UN will not allow its own soldiers to do anything but train. No coun- try, it seems, is willing to risk its own men clearing other people's mines.

Boutros-Boutros Ghali came here recently on his first major trip abroad as the UN Secretary-General, to boost the Cambodians' morale. He did not. He dropped the saddest clanger. Pestered by

journalists about promises reneged on, men, moneys rain, returnees and mines, he

turned to the little plump, ever-smiling moonfaced man sitting beside him and said, 'If all else fails, the infallible optimism of Prince Sihanouk here will see us through.' Someone should have told him it was the Prince who started the mess in the first place in 1970, flirting with the Chinese and North Koreans and sending the CIA into such a rage.

So there it is, great intentions running against the clock. So much to do, so little time, so much to gain, so much that is going sour. As I left for Pochentong airport to fly to Hanoi, my guide and interpreter, Sivath, stopped the car and pointed to the sky, to the crows circling high up above this city's glorious roofline.

'There were no crows here before the Khmer Rouge came in 1975,' she said. 'And they left when Pol Pot left in 1979. Now they are coming back.'

Michael Nicholson is foreign affairs corre- spondent for ITN.

Previous page

Previous page