Christopher Hudson on Ted Hughes and the Review

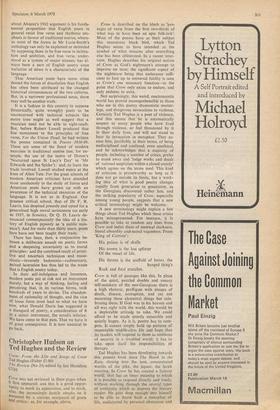

The Review (No 24) edited by Ian Hamilton (25p) - Crow was not reviewed in these pages when it first appeared; and this is a good oppor- tunity to mark its appearance, and to mark, also, the increasingly hostile attacks on it mounted by a curious rearguard of poets and critics : as, for example, above. Crow is described on the blurb as 'pas- sages of verse from the first two-thirds of what was to have been an epic folk-tale'.

Most of the poems have as their subject this monstrous black bird, which Ted Hughes seems to have intended as the symbol of what remains after everything else has been obliterated. In a recent inter- view, Hughes describes his original notion of Crow as God's nightmare's attempt to improve on man; the significant aspect of the nightmare being that endurance suffi- cient to face up to universal futility is seen as Crow's one necessary function—to the point that Crow only exists to endure, and only endures to exist.

Not surprisingly, this weird, oneiromantic world has proved incomprehensible to those who see in this poetry shamanistic mutter- ings, and dangerous invocations to violence. Certainly Ted Hughes is a poet of violence, and this means that he is automatically suspect to many people who have lived through violence, or feel threatened by it in their daily lives, and will not stand to hear its invocation in metaphor. They ac- cuse him, justifiably in their terms, of being undisciplined and confused, even unethical, and he acknowledges that a majority of people, including a number of critics, prefer to stand away and 'judge works and deeds of rational scepticism within a closed society' which agrees on the terms used. This kind of criticism is praiseworthy so long as it does not go outside its limits, but a work- ing idea of what is good poetry changes rapidly from generation to generation, as the Georgians discovered rather late, and the striking popularity of Crow, especially among young people, suggests that a new critical terminology might be welcome.

A new terminology might explain a few things about Ted Hughes which these critics have misrepresented. For instance, it is possible to take at random any lines from Crow and indict them of metrical slackness, literal absurdity and. moral vagueness. From 'King of Carrion': His palace is of skulls His crown is the last splinter Of the vessel of life.

His throne is the scaffold of bones, the hanged thing's Rack and final stretcher.

Crow is full of passages like this. in place of the quiet, puzzled doubts and uneasy self-mockery of the neo-Georgians there is a high rhetoric, profligate with images of death, disease, corruption, and yet not mourning these elemental things but cele- brating them. If God was in his heaven and all was right with the world, this would be a deplorable attitude to take, We could afford to be made quietly miserable and quietly happy. As it is, poetry has to com- pete. It cannot simply hold up pictures of respectable middle-class life and hope that its readers will respond to them as emblems of security in a troubled world; it has to take upon itself the responsibilities of therapy.

Ted Hughes has been developing towards this present book since The Hawk in the Rain, closing into the taut, concentrated worlds of the pike, the jaguar, the hawk roosting. In Crow he has created a fantasy world, that has an inner meaning to which it is possible to respond directly and freely, without Working through the several types of ambiguity which so impress the literary reader. He goes deep enough into himself to be able to throw back a metaphor of life, undistorted by personal obsessions and yet sufficiently integral to have general relevance. At this level it becomes both futile and impertinent to demand that in- dividual poems should have an intrinsic completeness and a message to be extracted, like an assortment of Christmas crackers; the transmission of experience, over the whole collection of poems, is the thought and the conclusion. This means that the poems, as units, become less important; but, because Hughes is a technically outstand- ing poet, it doesn't detract from their beauty and power.

It is disheartening to turn from Hughes. to the latest number of The Review, and find it stocked with a depreciating scholas- ticism, as if poetry were a closed world, full of miniature battles, fought on squares the size of a crossword puzzle. The key words are reticence, intelligence (a euphem- ism for rationality) and awareness (the awareness of the observer, not the partici- pant). The reticence, by the way, is not a Brechtian simplicity in face of suffering, but a pleasantly English disinclination to sound immoderately upset. In this Music. des Beaux Arts there are no screams; just the low sound of the torturer's horse scratching its rump on the tree.

The poets themselves don't take enough risks, and, quite bluntly, leave out too much. Alan Brownjohn, writing about the alleged demoralisation of English poets in face of American competition, tells us: 'It is per- fectly possible to write in a way that laces, understands and assumes the extremities of experience without parading the process'; and immediately after this, and after Molly Holden's poem ('Suburbia, like hanging, concentrates/The mind most wonderfully'), Michael Fried demonstrates this apoph- thegm Review-style: More rain than fountain water Splashes in the rough marble basin.

Is that bad or good? An index Of exhaustion or superfluity?

I don't know, but I dismount, and drink.

An index of exhaustion, I'd say. But it should be added, in fairness, that The Review is always worth buying for one or two things in it : in this case, a fine assessment of Lowell by John Bayley, and an interest- ing piece on the poets of East Germany by Michael Hamburger, one of the few English critics qualified to write with accu- racy about Brecht and his successors.

Previous page

Previous page