ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Kings over the water

La court des Stuarts a Saint-Germain-en- Laye au temps de Louis XIV (Musee des Antiquites nationales, Chateau de Saint-Germain, till 27 April) Portraits always have a message or two to put across, but seldom has so much hinged on the features of one little boy as on those of James Francis Edward Stuart, later James III, the Old Pretender. His changing image was the touchstone of the political legitimacy of the Stuart court in exile at the Château of Saint-Germain-en- Laye, where James II was lodged in state by his cousin Louis XIV, with a pension of 600,000 livres a year and all the respect due

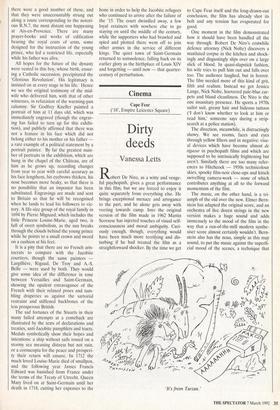

'James Francis Edward Stuart and his Sister Louise', by Nicholas de Largilliere, 1695 to a reigning monarch, after he fled Lon- don in 1688. This looking-glass court is the subject of an exhibition now being held at the Château, which has brought back many of the paintings made there, together with personal and political documents; and the most up-to-date historical research is assembled (in French) in its catalogue.

'If I had been told when I first arrived in France that I should have to remain here for two years, I should have been in despair,' Mary of Modena confided in 1711, 23 years after her flight from London with the infant prince. This was no reflec- tion on Le Roi Sold!, who welcomed them with all the magnanimity of the most pow- erful monarch on earth, inviting them to join in the splendid entertainments at Fontainebleau, Manly or Versailles, and paying punctilious respect to their rank in questions of precedence and fauteuils, to the occasional annoyance of the princesses of the blood. Among the various memoirs and engravings which describe the appear- ance and behaviour of the new arrivals is a delightful sheet of instructions written in Louis's own hand for the visit to Versailles of the Queen of England, to whom he became much attached, on the best way of seeing the gardens, with many strategic pauses for ice cream.

Gradually perceiving that their return to England would be later than they at first supposed, the King and Queen began to settle into a less provisional way of life as exiles in waiting, ordering their household in the many suites of apartments, providing musical and theatrical entertainments, receiving courtiers and appointing political secretaries, conferring honours and award- ing pensions. Contemporary documents show which rooms were allocated to whom — though the Château was remodelled in the last century and the original disposition of the rooms is shown in plans and models. Two strands ran through the daily life of the court: the unwavering conviction of the right to return to the throne of England, towards which all efforts were directed, and an equally unshakeable piety which sus- tained the King and Queen in their many times of disappointment, so that James was able to thank God for having taken away his kingdom 'to wake me from the lethargy of sin'. He spent his last years composing works of devotion, and was considered a serious candidate for sainthood on his death in 1701, to the point that when his body was opened so that his various entrails could be deposited in different chapels, bits of linen were dipped in his blood to be handed out as relics. Two of them are on show here, alongside letters and reports testifying to miraculous cures obtained through his intercession. It seems there were a good number of these, and that they were unaccountably strung out along a route corresponding to the notori- ous R.N.7, the most distant one happening at Aix-en-Provence. There are many prayer-books and works of edification bearing the royal coats of arms, some designed for the instruction of the young prince, who led a restricted life, especially while his father was alive.

All hopes for the future of the dynasty were vested in this boy, whose birth, ensur- ing a Catholic succession, precipitated the 'Glorious Revolution'. His legitimacy is insisted on at every stage in his life. Hence we see the original testimony of the mid- wife who delivered him, with that of other witnesses, in refutation of the warming-pan calumny. Sir Godfrey Kneller painted a portrait of him at 11 days old, which was immediately engraved (though the engrav- ing has failed to turn up for this exhibi- tion), and publicly affirmed that there was not a feature in his face which did not belong either to his mother or his father — a rare example of a political statement by a portrait painter. By far the greatest num- ber of portraits in the exhibition, which are hung in the chapel of the Château, are of him as he grows up, recording changes from year to year with careful accuracy as his face lengthens, his eyebrows thicken, his nose becomes more beaky, so that there is no possibility that an impostor has been substituted. Engravings are made and sent to Britain so that he will be recognised when he lands to lead his followers to vic- tory. A life-size group of the royal family in 1694 by Pierre Mignard, which includes the little Princess Louise-Marie, aged two, is full of overt symbolism, as the sun breaks through the clouds behind the young prince while he points to a small crown and sword on a cushion at his feet.

It is a pity that there are no French aris- tocrats to compare with the Jacobite courtiers, though the same painters — Largilliere, Rigaud, De Troy and A.-S. Belle — were used by both. They would give some idea of the difference in tone between Versailles and Saint-Germain, showing the opulent extravagance of the French with their relaxed poses and tum- bling draperies as against the sartorial restraint and stiffened backbones of the less prosperous British.

The sad fortunes of the Stuarts in their many failed attempts at a comeback are illustrated by the texts of declarations and treaties, anti-Jacobite pamphlets and tracts. Medals symbolically show their hopes and intentions: a ship without sails tossed on a stormy sea meaning distress but not ruin, or a cornucopia for the peace and prosperi- ty their return will ensure. In 1712 the much loved Louise-Marie died of smallpox, and the following year James Francis Edward was banished from France under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht. Queen Mary lived on at Saint-Germain until her death in 1718, cutting her expenses to the bone in order to help the Jacobite refugees who continued to arrive after the failure of the '15. The court dwindled away, a few loyal retainers with nowhere else to go staying on until the middle of the century, while the supporters who had brawled and spied and plotted there went off to join other armies in the service of different kings. The quiet town of Saint-Germain returned to somnolence, falling back on its earlier glory as the birthplace of Louis XIV and forgetting — until now — that quarter- century of perturbation.

Previous page

Previous page