ARTS

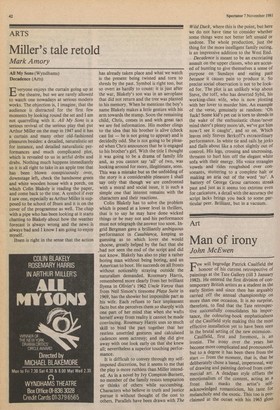

Miller's tale retold

Mark Amory

All My Sons (Wyndhams) Decadence (Arts) Everyone enjoys the curtain going up at the theatre, but we are rarely allowed to watch one nowadays at serious modern works. The objection is, I imagine, that the audience is distracted for the first few moments by looking round the set and I am not quarrelling with it. All My Sons is a serious revival of the serious play that put Arthur Miller on the map in 1947 and it has a curtain and many other old-fashioned pleasures besides: a detailed, naturalistic set for instance, and detailed naturalistic performances and much complicated plot, which is revealed to us in artful dribs and drabs. Nothing much happens immediately so it is all right to take in an apple tree that has been blown conspicuously over, downstage left, check the handsome green and white wooden house with a porch, on which Colin Blakely is reading the paper, and come back to the tree. A symbol if ever I saw one, especially as Arthur Miller is supposed to be school of Ibsen and it is on the cover of the programme as well. The chap with a pipe who has been looking at it starts chatting to Blakely about how the weather forecast is always wrong and the news is always bad and I know I am going to enjoy myself.

Ibsen is right in the sense that the action has already taken place and what we watch is the present being twisted and torn to shreds by the past. Symbol is right too, but so overt as hardly to count: it is just after the war, Blakely's son was in an aeroplane that did not return and the tree was planted in his memory. When he mentions the boy's name Blakely makes a little gesture with his arm towards the stump. Soon the remaining child, Chris, comes in and with great tact we are fed information. His mother clings to the idea that his brother is alive (check cast list — he is not going to appear) and is decidedly odd. She is not going to be pleased when Chris announces that he is engaged to his brother's girl. With the title I thought it was going to be a drama of family life and, as you cannot say 'all' of two, was looking around for more, illegitimate, sons. This was a mistake but as the unfolding of the story is a considerable pleasure I shall say only that though we are confronted with a moral and social issue, it is such a simple one that interest remains with the characters and their reactions.

Colin Blakely has to solve the problem which is posed at a lower level in thrillers, that is to say he may have done wicked things or he may not and his performance must not telegraph the answer too soon. Ingrid Bergman gave a brilliantly ambiguous performance in Casablanca, keeping us guessing as to which lover she would choose, greatly helped by the fact that she ,had not seen the end of the script and did not know. Blakely has also to play a rather boring man without being boring, and an American to boot. He succeeds on all fronts without noticeably straying outside the naturalism demanded. Rosemary Harris, remembered more clearly from her brilliant Hyena in Olivier's 1962 Uncle Vanya than from Neil Simon's tiresome Plaza Suite in 1969, has the showier but impossible part as his wife. Each refuses to face unpleasant facts but she perceives them so sharply with one part of her mind that when she wafts herself away from reality it cannot be made convincing. Rosemary Harris uses so much skill to bind the part together that her restless unsettled gestures and calculated cadences seem actressy; and she did give away with one look early on that she knew all; nevertheless a superior touching performance.

It is difficult to convey through my selfimposed discretion, but it seems to me that the play is more ruthless than Miller intended. As in a novel by Ivy Compton-Burnett, no member of the family resists temptation or thinks of others while succumbing. Characters who believe in truth and justice pursue it without thought of the cost to others. Parallels have been drawn with The Wild Duck, where this is the point, but here we do not have time to consider whether some things were not better left unsaid or undone. The whole production, just the thing for the more intelligent family outing, is an impressive addition to the West End.

Decadence is meant to be an excoriating assault on the upper classes, who are accused of hunting to give themselves a sense of purpose on Sundays and eating pate because it causes pain to produce it. So precise social observation is not to be looked for. The plot is an unlikely wisp about Steve, the toff, who has deserted Sybil, his working-class wife, who is now plotting with her lover to murder him. An example of the verse, genuinely at random: 'Oh fuck! Some kid's pet cat is torn to shreds in the wake of the enthusiastic chase/never mind there's plenty more/ah, we've got him now/I see it caught', and so on. Which leaves only Steven Berkoff's extraordinary performance. In white tie and tails he jerks and flails about like a robot slightly out of control. His legs, crossing and uncrossing, threaten to hurl him off the elegant white sofa with their energy. His voice strangles vowels and rides roughshod over consonants, stuttering to a complete halt or making an aria out of the word `no'. A battery of George Grosz cartoons streak past and just as it seems too extreme even for caricature, a detail with the accuracy the script lacks brings you back to some particular peer. Brilliant, but in a vacuum.

Previous page

Previous page