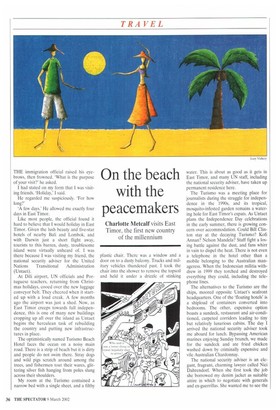

On the beach with the peacemakers

Charlotte Metcalf visits East Timor, the first new country of the millennium

THE immigration official raised his eyebrows, then frowned. 'What is the purpose of your visit?' he asked.

I had stated on my form that I was visiting friends. 'Holiday,' I said.

He regarded me suspiciously. Tor how long?'

'A few days.' He allowed me exactly four days in East Timor.

Like most people, the official found it hard to believe that I would holiday in East Timor. Given the lush beauty and five-star hotels of nearby Bali and Lombok, and with Darwin just a short flight away, tourists to this barren, dusty, troublesome island were virtually unheard of. I was there because I was visiting my friend, the national security adviser for the United Nations Transitional Administration (Untaet).

At Dili airport, UN officials and Portuguese teachers, returning from Christmas holidays, cooed over the new luggage conveyor belt. They cheered when it started up with a loud creak. A few months ago the airport was just a shed. Now, as East Timor creeps towards full independence, this is one of many new buildings cropping up all over the island as Untaet begins the herculean task of rebuilding the country and putting new infrastructures in place.

The optimistically named Turismo Beach Hotel faces the ocean on a noisy main road. There is a strip of beach but it is dirty and people do not swim there. Stray dogs and wild pigs scratch around among the trees, and fishermen tout their wares, glittering silver fish hanging from poles slung across their shoulders.

My room at the Turismo contained a narrow bed with a single sheet, and a filthy plastic chair. There was a window and a door on to a dusty balcony. Trucks and military vehicles thundered past. I took the chair into the shower to remove the topsoil and held it under a drizzle of stinking water. This is about as good as it gets in East Timor, and many UN staff, including the national security adviser, have taken up permanent residence here.

The Turismo was a meeting place for journalists during the struggle for independence in the 1990s, and its tropical, mosquito-infested garden remains a watering hole for East Timor's expats. As Untaet plans the Independence Day celebrations in the early summer, there is growing concern over accommodation. Could Bill Clinton stay at the decaying Turismo? Kofi Annan? Nelson Mandela? Staff fight a losing battle against the dust, and fans whirr in vain to dispel the heat. There is not even a telephone in the hotel other than a mobile belonging to the Australian manageress. When the Indonesian militia withdrew in 1999 they torched and destroyed everything they could, including the telephone lines.

The alternatives to the Turismo are the ships, moored opposite Untaet's seafront headquarters. One of the 'floating hotels' is a shipload of containers converted into bedrooms. The other, expensive option boasts a sundeck, restaurant and air-conditioned, carpeted corridors leading to tiny but relatively luxurious cabins. The day I arrived the national security adviser took me aboard for lunch. Bypassing American marines enjoying Sunday brunch, we made for the sundeck and ate fried chicken washed down by criminally expensive and vile Australian Chardonnay.

The national security adviser is an elegant, fragrant, charming lawyer called Niel. Dahrendorf. When she first took the job she borrowed my denim jacket as suitable attire in which to negotiate with generals and ex-guerrillas. She wanted me to see the island before she leaves, before Untaet's handover to the new government.

She commandeered a Landcruiser complete with air-conditioning, CD player and satellite phone and the number plate UNTAET 2, and we set off into the interior. We drove past Dollar Beach, a strip of deserted white sand where locals charge expats a dollar to swim and picnic there on Sundays. The beaches became bleak and black and the terrain salty and dry as we approached the mountains. Soon we were driving past Thai and Jordanian barracks, and being edged off the road by a convoy of Australian peacekeeping forces.

Up in Baucau the air was cool. We lunched off salt cod and eggs on a terrace overlooking a school. On the hill above us, the remains of a huge and once beautiful covered market dominated the town, a reminder of Portugal's colonial past. Once Baucau must have been one of several pretty hill towns, a welcome escape from the malevolent heat and humidity of the coast. Today burnt-out shells of buildings line the roads of rural villages, sagging, crumbling and pockmarked with bullets. Eventually the grisly and repetitive evidence of such deliberate and methodical mass destruction becomes depressing. Baucads Flamboyant Hotel was a torture centre used by the Indonesian militia. The island's natural beauty cannot compensate for the constant grim reminder of its sorry recent history.

Back in Dili the national security adviser and I went to a fish restaurant on the beach to drink wine and watch the sunset. She sighed as we drew up alongside a large herd of UN vehicles. Just for an evening, she had hoped to avoid her colleagues. but Dili is a small town with few restaurants. Anonymity and privacy are out of the question. Sit in the garden at the Turismo and within minutes someone you know will arrive. Even during my brief stay there it was impossible to eat breakfast without someone I had met joining me. Yet this is a temporary community of expatriate administrators, and soon it will be gone. Already the rounds of farewell parties were beginning as Untaet prepared to withdraw.

Few of us can forget the news footage of the East Timorese walking for miles from remote villages to vote for independence. They represented one of the greatest victories for democracy at the end of the last century. It is testimony to their courage, resistance and determination that in May this year this shabby, dusty and impoverished island stands to go down in history as the first new country of the millennium.

Charlotte Metcalf is an independent filmmaker.

Previous page

Previous page