ARTS

Nothing if not original, the Architectu- ral Association has chosen to bind a most elegantly designed catalogue about the Swedish architect Sigurd Lewerenz (Sigurd Lewerenz 1885-1975: the Dilemma of Clas- sicism, £45) in a material which both feels and smells nasty. Remove the dust-jacket and you will find the explanation on the reverse: `Englisli Abrasives. . . silicon car- bide paper'. The symbolism is clear: the buildings inside are hard, rough, workman- like, uncompromising.

Lewerenz built little. He is best known as the associate of Gunnar Asplund on the Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm. As- plund was the subject of a magnificent exhibition at the AA last year and this follow-up is as good, with furniture on display as well as original drawings. But this exhibition is more than a further examination of the great contribution of Sweden to 20th-century architecture. Nor is it just an exercise in that one-upmanship that seeks to extol the obscure, and an avant-garde endorsement of real integrity that promotes the silent, often unsuccessful architect over the famous and successful like Asplund, for Lewerenz was dismissed from the Woodland Cemetery in 1934 and many of his winning competition entries were never realised.

The AA is making an ideological state- ment about Lewerenz because his move from Classicism to Modernism was irrev- ersible and in him the flame of the Modern Movement burned hard and bright. As with Asplund, his early work was characte- rised by an austere but Romantic revival of the Classical and his chapel of 1922-25 at the Woodland Cemetery has been de- scribed as the finest work of the whole movement of 'Nordic Classicism'. But, after the 1940s, Lewerenz built two chur- ches that can only be described as Brutal- ist: raw, uncompromising shapes with clearly expressed structures in steel and concrete and great rough masses of ordin- ary bricks. Lewerenz himself gave no explanations for this change, but Colin St John Wilson argues, in a brilliant polemical essay, that

he found the Classical language no longer able to carry meaning as before. So what is at issue in his late buildings is not the inadequa- cy of the Classical language to deal with functionalism, but rather the exhaustion of its powers to deal even with its original province — that realm of building that Loos defined in terms of the tomb and the monu- ment. And in that exhaustion, it had become a language that can only tell a lie.

There speaks the architect of the new British Library and it is the attitude of the AA against the current Classical Revival and any other deviation from the party

Architecture

Sigurd Lewerenz (Architectural Association, till 11 February)

The rough and the smooth

Gavin Stamp

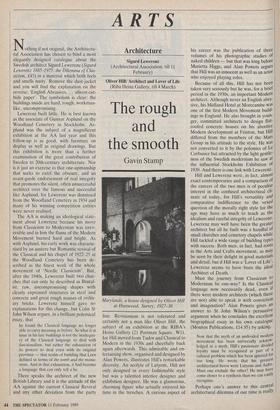

Marylands, a house designed by Oliver Hill at Hurtwood, Surrey, 1927-30 line. Revisionism is not tolerated and certainly not a man like Oliver Hill, the subject of an exhibition at the RIBA's Heinz Gallery (21 Portman Square, W1), for Hill moved from Tudor and Classical to Modern in the 1930s and cheerfully back again afterwards. This admirable and en- tertaining show, organised and designed by Alan Powers, illustrates Hill's remarkable diversity. An acolyte of Lutyens, Hill not only designed in every fashionable style but was a talented interior designer and exhibition designer. He was a glamorous, charming figure who actually enjoyed his time in the trenches. A curious aspect of

his career was the publication of three volumes of his photographic studies of naked children — but that was long before Marietta Higgs, and Alan Powers argues that Hill was an innocent as well as an actor who enjoyed playing roles.

Because of all this, Hill has not been taken very seriously but he was, for a brief period in the 1930s, an important Modern architect. Although never an English abra- sive, his Midland Hotel at Morecambe was one of the first Modern Movement build- ings in England. He also brought in youn- ger, committed architects to design flat- roofed concrete houses on his abortive Modern development at Frinton, but Hill differed from the members of the Mars Group in his attitude to the style. He was not converted to it by the polemics of Le Corbusier but attracted by the light gentle- ness of the Swedish modernism he saw at the influential Stockholm Exhibition of 1930. And there is one link with Lewerenz.

Hill and Lewerenz were, in fact, almost exact contemporaries and a comparison of the careers of the two men is of peculiar interest in the confused architectural cli- mate of today, for Hill's versatility and comparative indifference to the vexed question of the morally right style for the age may have as much to teach as the idealism and careful integrity of Lewerenz• Lewerenz may well have been the greater architect but all he built was a handful of small churches and cemetery chapels while Hill tackled a wide range of building types with success. Both men, in fact, had roots in the Arts and Crafts movement, as maY be seen by their delight in good materials and detail, but if Hill was a 'Lover of Life', Lewerenz seems to have been the ideal Architect of Death.

Must the journey from Classicism to Modernism be one-way? Is the Classical language now necessarily dead, even if there were modern architects (which there are not) able to speak it with conviction and imagination? Alan Powers gives all answer to St John Wilson's persuasive argument when he concludes the excellent biographical essay in his own catalogue (Mouton Publications, £14.95) by asking,

Now that the myth of an undivided modern movement has been universally acknow- ledged as a myth, Hill's passionate divided loyalty must be recognised as part of a cultural problem which has been ignored for too long. He wrote that his greatest architectural heros were Lutyens and Aalto. Must one exclude the other? He may have come closer to a synthesis than we can easily recognise.

Perhaps one's answer to this central architectural dilemma of our time is really a question of temperament, whether national or personal. It depends, perhaps, on whether one sympathises with a smooth, undoctrinaire, accommodating Englishman or an austere, uncompromis- ing, gloomy Swede. Or is it just a matter of whether you prefer your books bound in sandpaper or more comfortably covered in laminated card?

Previous page

Previous page