The Torch of Virtue

Henry James: Selected Literary Criticism. Edited by Morris Shapira with an introduction by F. R. Leavis. (Heinemann, 30s.) To this age, split between the passion cherished in private and the gestures demanded in public, James gave a defining parable in his wonderfully deft 'The Private Life.' Ostensibly a mystery— why is a certain great writer so banal in public, why does a certain famous public figure seem to vanish when left alone—it has a ghostly resolu- tion which pinpoints the latent schizophrenia of the age. The writer is in fact two people, one a genius who stays in his room and writes in the dark, the other a bourgeois deputy for dining and gossiping in the 'vulgar and stupid' world. The public figure is indeed so utterly devoted to public appearances (`he had a costume for every func- tion and a moral for every costume') that he has no private life to fall back on. The disguises have absorbed the man. In such an age how should the artist proceed, how survive? James returns often to the theme of necessary renunciation—it is the ironic yet sincere 'Lesson of the Master' who does not practise what he preaches. Renun- ciation not only of public reward but domestic consolation.

Clearly James's old fear of the enfeebling demands of women is still at work, but his xsthetic ideal is obviously earnestly conceived. Art must 'affitm an indispensable truth' and the artist must, like the collaborators in the story of that name, sacrifice both country and family to make that affirmation. Such art 'makes for civili- sation'; ultimately it.'works for human happiness.' James was aware of so much around him that did not. In fact, the visible social realities of his age were insufficient to stimulate great art, as is amusingly brought out in 'The Real Thing.' A genteel couple in need of money seek work from a book illustrator as models. But they are 'all con- vention and patent-leather.' The real thing is the dead thing : it offers no suggestion to the imagina- tion, no scope for 'the alchemy of art.' The truly `real' has to be approached by subtler means. If the Jamesian artist can and must renounce, many of his characters who are inexorably involved in this society can only succumb. There is a sur- prising amount of death in these stories. 'Brook- smith,' the butler who develops an artistic imagi- nation which he cannot employ after his sym- pathetic master dies, withers away. Agatha Grice, torn apart by the forces exerted by her English husband and her American brother, commits suicide ('A Modern Warning'). Grace Mavis, the Poor American girl who is trifled with and gossiped about on the ship which is taking her to an arranged and unsought marriage, jumps overboard (`The Patagonia'). Louisa Chantry, overwhelmed by the shame of having revealed a hidden passion, dies almost immediately. (`The Visits'), And in perhaps the finest story in these volumes, 'The Pupil,' Morgan Moreen's heart gives out under the accumulated burden of shame and the sudden shattering impact of a prospective release from his wretched family. Thus society takes its victims. In such a world conscience is at a premium : yet James was just enough to per- ceive that conscious morality may contain its own inhumanity. Laura Wing in 'A London Life,' is an innocent American girl revolted by the infected atmosphere of London life. Yet her moral eye is barbarous : it is either blind or cruel. Having lost

`the just measure of things' she collapses from hysterical indictments to personal panic. She flees whence she came, taking with her her hypertro- phied conscience which could not adjust to the complexities of social living. Adela Chart, in 'The Marriages,' with her 'possibly poisoned and in- flamed judgment' self-righteously takes it upon herself to prevent her father from re-marrying by a series of calculated mendacities. She rationalises her possessiveness as an act of virtue. Her brother's outraged reproach can stand as society's outcry against the too severe and, too often, the self-deceiving moralist. 'You invented such a tissue of falsities and calumnies, and you talk about your conscience.' True morality for James is never a matter of simple-minded outrage or bullying interference. A finer, more humane scale of assessment must be called into play.

Some characters, it is true, are strong enough to enter the vicious theatrical game .of social life and emerge victorious with their virtue unimpaired— thus Rose Tramore determines to force society to reaccept her disgraced mother, and she man- ages to 'triumph with contempt.' Yet even in the lightest tales, society is a matter of 'fangs and scales' with a manipulating egotism motivating all too much of the elegant interplay. It is a society haunted by vengeful ghosts (`Sir Edmund Orme'); a setting for recurring pains, repeated abandon- ments, and regrets too late by years (The Wheel of Time'). In all, a society much like that brilli- antly described household in 'The Pupil': 'specu- lative and rapacious and mean.' And in that household James embroils one of his most memorable children. Foi Morgan, in 'the morn- ing twilight of his childhood,' beset by 'curious intuitions and knowledges' embodies a noble and stoical ideal which makes him 'privately resent the general quality of his kinfolk.' He hates the 'fifth-rate social ideal' of his family, their total preoccupation with mere appearances. His em- battled and foredoomed integrity has much in common with that of the artist and his death betokens more than the premature expiration of innocence. Like Maisie in a later novel, like James himself, he 'keeps the torch of virtue alive in an air tending infinitely to smother it.' He died : James lived. To our great moral, our great human advantage.

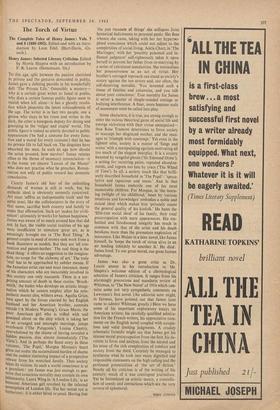

James was also a great critic as Dr. Leavis attests in his introduction to Mr. Shapira's welcome edition of a chronological selection of James's criticism. It ranges from his alarmingly precocious and mandarin review of Whitman, to 'The New Novel' of 1914 which con- tains some not very sympathetic comments on Lawrence's first novel. (An editorial note might, in fairness, have pointed out that James later came to admire Whitman greatly.) Here we have some of his important exploratory essays on American writers; his carefully qualified admira- tion for the French writers, his appreciative com- ments on the English novel coupled with scrupu- lous and valid limiting judgments. A crudely schematic formula might say, that James got his intense moral preoccupation from the first, his de- v otion to form and analysis from the second and his sense of the rich complexities of conduct and society from the third. Certainly he managed to' synthesise what he took into many dignified and responsible statements on the high calling and the profound potentialities of 'the art of fiction.' Nearly all his criticism is of the writing of his century; much of it was contingent journalism. Yet he formulated an artistic stance, a constella- tion of creeds and convictions which are the very reverse of ephemeral.

TONY TANNER

Previous page

Previous page