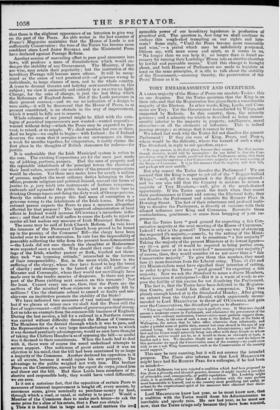

TOPICS OF THE DAY.

THE MONARCHY AND THE PEERAGE.

IF any reply has been made to the arguments by which we endea- voured to controvert Lord JOHN RUSSELL'S assertion, that to re- form the House of Peers would bring the Monarchy into unques- tionable danger, we have not seen it. The Leeds Mercury agrees with Lord JOHN; and regards it as " unquestionable that the " abolition of the Aristocratic branch of the Legislature would be very speedily followed by knocking off the Monarchical head." But it is not proposed to abolish the Aristocratic branch of the Legislature : this is a misrepresentation very common with the advocates of Irresponsible Legislation. It is also very easy to designate any proposition as tending (literally or figura- tively) to knock off the King's head : but not a shadow of reason is adduced to prove that such would be the consequence of con- verting; the present House of' Peers into an elective assembly. It will not be expected, therefore, that we should surrender the opinion maintained in the last number but one of this journal, that all apprehensions of danger to the Crown from a reform of the Peers House are groundless. The Leeds Mercury, however, undertakes to answer for us, on a point of some del:eacy, and to an effect which we certainly are not prepared to make good- " We are quite sure that a paper of less ability thau the Spectator would be able to find more wounds of objection to an hereditary King than to hereditary Lords. For example, suppose the editor to try his hand at an argument on the act if his .Majesty last November, we will engage for it Inc would make out a stronger case against Mouarchy than he has ever made out against the l'eerage."

The objection to the Peers is that they disregard the wishes of the Nation, as expressed in the votes of our Representatives. They are perfectly independent of the Commons, and act as if they were so. If the King were placed in similar circumstances, and acted with the same contempt of the National Representa-

tives, the argument against an hereditary Monarchy would be irresistible. e•But what is the fact? We take the ease presented to us by the Leeds journalist ; and we find that the King changed his course in compliance with the declared wish of the House of Commons. He took a new set of Ministers in November, and appealed to the Electors for their opinion on what he had done :

that opinion was adverse to the proceeding ; and in the April fol- lowing he took back his old Ministers again. The required change was not only made, but very speedily brought about. Never was there a more palpable proof of the necessity under which a King of England is placed of complying with the wishes of the majority of the People, when made known through the recognized organs of their will. In fact, the King had no choice : he is dependent on the House of Commons for the means of carrying on the Government—nay, for the means of personal subsistence. What more could be required of the President of a Republic?

But how stands the case with the Lords? They altered not their course. On the contrary, they threw aside the semblance of Liberalism, and treated the measures of the People's Represen- tatives, and of the Ministers restored by the Monarch because the People's Representatives supported them, with wanton defiance. There was not a single bill of importance sent up to them by the Commons, that they did not contemptuously reject or insolently mutilate. And who could say them " nay ?" They were respon- sible to none. None could call them to account. They had no constituents. Their "supplies" dependA on no annual vote : ELLENHOROUGH'S sinecure and LYNDHURST'S pension are as yet protected by statute. Here, then, we see the difference between the position of the hereditary Lawgivers and the hereditary Monarch. The Monarch, as recent experience proves, is essentially responsible: the Peers are irresponsible authors of mischief: therefore, while a change is not required in the Monarchy, it is seen to be necessary in the constitution of the House of Peers.

One of the common objections to an hereditary Monarchy is, that a King is more costly than the elective Chief Magistrate of a Republic. To this we reply, that he needs not be. The same power which forced the Sovereign to take back his discarded Cabinet, can cut down the Civil List. No alteration of the Consti- tution is required to effect that, should it be deemed desirable.

It is possible that the King for the time being may be a mad- man. This is supposing the worst case that can happen. Well, it belongs to Parliament—in other words, it depends on the House of Commons, the dealer out of the money—to determine who shall be Regent. Mr. PITT denied the right of the late King to assume the Regency, on the first derangement of GEORGE the Third ; and the House of Commons by a considerable majority resolved, that it was the right of Parliament to supply the defect in the personal exercise of the Royal authority. Thus we see that even the extreme case of imbecility or madness—the se- verest trial of Sovereignty by descen:—is safely provided for; and that, in effect, the People s Representatives nominate the Regent as well as his Ministers.

The Leeds Mercury lays great stress on the advantage of "stability " in a Government ; and we are not disposed to under- va!ee it. But does the irresponsible legislative authority of the Peers contribute to stability ? Will a lengthened struggle betweea the two Chambers render the Government firm, even suppoting that even:ually the Peers should yield? No one, however, can say

that there is the slightest appearance of an intention to give way on the part of the Peers. An able writer in the last number of

Fraser's Magazine maintains that the House of Lords is not sufficiently Conservative: the tone of the Tories has become more confident since Lord Joust RUSSELL and the Ministerial Press have declared against Peerage Reform.

Another session of unavailing effort to pass good measures into laws, will produce a mass of dissatisfaction which would en- danger the stability of any Government. The Ministry, if they are wise, may retain their popularity ; but the institution of the hereditary Peerage will become more odious. It will be recog- nized as the cause of vast practical evil—of grievous wrong to

individuals' to large classes of men, and to the whole country. A truce to dreamy theories and holyday sentimentalisms on this

subject ; we view it eminently and entirely in a PRACTICAL light. Change, for the sake of change, is just the last thing which the Reformers of England desire. But if the Lords persevere in their present courses,—and we see no indication of a design to turn aside,—it will be discovered that the House of Peers, as at present constituted, is an obstacle in the way of improvement, which it would be folly not to remove.

Whole columns of our journal might be filled with the cata- logue of practical improvements now wanted—wanted urgently— wanted without delay—which the Peers may be expected to pre-

vent, to retard, or to cripple. We shall mention but two or three. And we begin—we ought to begin— with Ireland : for if Ireland deserves the room that it occupies in our newspapers six times a week for months together, for vituperation, it surely claims the first place in the thoughts of British statesmen for redress—for justice. It is undeniable that the Irish Municipal system is rotten to the core. The existing Corporations are for the most part made up of jobbing, partisan, paupers. Had the men of property and the reputable inhabitants of the principaltowns the election of their local rulers, scarcely one member of the present corporations would be chosen. Yet these men make laws for nearly a million of persons, neglect the most ordinary duties belonging to their offices, promote religious and political discord, convert the forms of

justice (e. g. jury trial) into instruments of factious vengeance,

embezzle and squander the public funds, and pass their time ia drinking Orange toasts and doing the dirty work of Orange patrons. Surely the refusal to purge this foul mass of corruption is a grievous wrong to the inhabitants of the Irish towns. But what rational person expects the Peers to pass a measure altogether

effectual for that purpose? The improved administration of local affairs in Ireland would increase O'CONNELL'S immediate influ- ence; and that of itself will suffice to cause the Lords to reject or render all but useless any measure of Irish Municipal Reform.

The same may be said of Irish Church Reform. In vain have the interests of the Protestant Church been proved to be bound up in the passing of the Commons' Bill—the clergy have been banded over to law and starvation. In vain has the impossibility of peaceably collecting the tithe from the peasant been demonstrated —the Lords did not care though the slaughter at Rathcormac were repeated once a month. Why should they care? the suffer- ings of the Irish, whether pastors or flock, touched not them: they. took "an imposing attitude," intrenched in the fortress

of their irresponsibility. But, in the mean while, bitter is the suffering of the clergy, whom they have forced to beg the bread of charity ; and stronger is the hatred of the wild millions of

Munster and Connaught, whom they would not unwillingly have made over to the tender mercies of dragoons. Is there any pros-

pect of the Peers yielding next session on this measure ? Not the least. Cannot every one see, then, that the Peers are the authors of the mischief whose existence is so sensibly felt by millions ? Can the obstinate refusal to amend so faulty and mis- chievous an institution promote the stability of the State?

We have indicated two measures of vast national importance; but if we glance at minor ones we shall find the Peers still the

foes of improvement—still the authors ofgrievouspractical wrong. Let us take an example from the common-life business of England. During the last session, a bill for a railroad in a Northern county was carried without difficulty through the House of Commons. The Members for the district through which it was to pass, and the Representatives of a very large manufacturing town to which it was deemed peculiarly advantageous, would as Soon have thought of taking the Chiltern Hundreds as of opposing the bill—so useful was it deemed to their constituents. When the Lords had to deal with it, there were of course the usual underhand attempts to secure support. One nobleman of great estate said it was an objection in his mind, that the bill had been sanctioned by so large a majority of the Commons. Another declared his opposition to it at all events, because it would injure his own property. The advantage to the public weighed not with him. His brother Peers on tbe Committee, moved by the esprit du corps, joined him and threw out the bill. Had these Lords been members of an elective and responsible body, they would have voted differently, we are sure.

Is it not a notorious fact, that the opposition of certain Peers to measures of internal improvement is bought off, every session, by enormous sums, given nominally as purchase-money for land, through which a road, or canal, or railway is to pass? Would a Member of the Commons dare to make such terms—to ask the same price for a slice of his estate, that a Peer can obtain ?

Thus it is found that in large and in small matters the irrei sponsible power of our hereditary legislators is productive of practical evil. The question is, how long we shall continue to endure this rough-shod trampling on our rights and inte- rests? Some reply, "Until the Peers become more reasonable and wise," — a period which may be indefinitely postponed. Others say, with more sense and spirit, as it seems to us, "No longer than we can help it; no longer than is found ne- cessary for turning their Lordships' House into an elective chamber by lawful and peaceable means." Until this change is brought about, and both Houses of Parliament are made to legislate at least on the same principles, it is idle to talk about the stability of the Government,—meaning thereby, the preservation of the Peers' House as it is.

Previous page

Previous page