Theatre 2

The King and I (Battersea Arts Centre) Killing Rasputin (Bridewell) The Snow Palace (Tricycle)

Attack on chauvinism

Sheridan Morley

AOklahoma! continues to make its Royal National progress into the West End (Lyceum from 20 January), and then doubtless on to Broadway, I am still having trouble with the much-advertised notion of its 'rediscovery'. True, the choreography is all new, but nothing else in Trevor Nunn's award-winning production strikes me as remotely new, least of all the idea that Poor Jud has somehow been revitalised and darkened; Rod Steiger was doing all of that and much better in the 1955 movie by Fred Zinnemann.

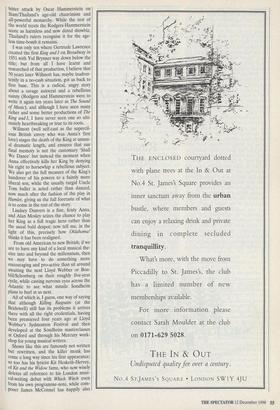

If, however, you want to see what a real Rodgers-and-Hammerstein rediscovery looks like this Christmas, go over the river to the Battersea Arts Centre where Phil Willmott has, until 10 January, a breathtak- ing small-stage King and I. Often under- cast, hopelessly underfinanced in a set looking like the back room of a Thai take- away restaurant, this is nevertheless a bril- liant reminder of how it all started, with a book of memoirs and then a non-musical film called Anna and the King of Siam. Now, stripped of its widescreen glitz and the haunting presence of Yul Brynner, you suddenly see why the show remains banned in Thailand, where they have recently also refused to allow the movie remake; Thai beer firms in London have even declined to be involved here as sponsors.

Why? Because, seen once again but for the first time in half a century as a play with music, this King and I emerges as a bitter attack by Oscar Hammerstein on Siam/Thailand's age-old chauvinism and all-powerful monarchy. While the rest of the world treats the Rodgers-Hammerstein score as harmless and now dated showbiz, Thailand's rulers recognise it for the age- less time-bomb it remains.

I was only ten where Gertrude Lawrence created the first King and I on Broadway in 1951 with Yul Brynner way down below the title; but from all I have learnt and researched of that production, I believe that 50 years later Willmott has, maybe inadver- tently in a no-cash situation, got us back to first base. This is a radical, angry story about a savage autocrat and a rebellious nanny (Rodgers and Hammerstein were to write it again ten years later as The Sound of Musk), and although I have seen many richer and some better productions of The King and I, I have never seen one so ulti- mately heartbreaking or true to its roots.

Willmott (well self-cast as the supercil- ious British envoy who was Anna's first love) stages the death of the King at unusu- al dramatic length, and ensures that our final memory is not the customary `Shall We Dance' but instead the moment when Anna effectively kills her King by denying his right to horsewhip a rebellious subject. We also get the full measure of the King's handover of his powers to a faintly more liberal son, while the usually turgid Uncle Tom ballet is acted rather than danced, now much after the fashion of the play in Hamlet, giving us the full foretaste of what is to come in the rest of the story.

Lindsey Danvers is a fine, feisty Anna, and Alan Mosley seizes the chance to play her King as a full tragic hero rather than the usual bald despot; now tell me, in the light of this, precisely how Oklahoma! thinks it has been realigned.

From old American to new British; if we are to have any kind of a local musical the- atre into and beyond the millennium, then we may have to do something more encouraging and pro-active than sit around awaiting the next Lloyd Webber or Bou- blil/Schonberg on their roughly five-year cycle, while casting nervous eyes across the Atlantic to see what missile Sondheim plans to hurl at us next.

All of which is, I guess, one way of saying that although Killing Rasputin (at the Bridewell) still has its problems it arrives there with all the right credentials, having been premiered four years ago at Lloyd Webber's Sydmonton Festival and then developed at the Sondheim masterclasses at Oxford and through his Mercury work- shop for young musical writers.

Shows like this are famously not written but rewritten, and the killer monk has come a long way since his first appearance; so too has his lyricist Kit Hesketh-Hervey, of Kit and the Widow fame, who now wisely deletes all reference to his London musi- cal-writing debut with Which Witch even from his own programme-note, while com- poser James McConnel has happily also overcome his recent disaster with Dame Edna Everage at the Haymarket.

But the experiences and still early careers of Hesketh-Hervey and McConnel suggest that the path of a British musical writer is still a lot more hazardous than that of a playwright, to whom the right to fail is always more readily extended by crit- ics and audiences alike. In that sense and many others Rasputin is a courageous show, given us now in a spare kind of chamber production by Ian Brown. True, the old drama queen still takes a long time to be killed and even longer to die, which essentially is all that happens here; around the periphery, the complete and utter his- tory of Russia in first world war nervous breakdown is apt to look a little sketchy when performed by a dozen actors on a bare stage.

Tolstoy and Chekhov and Dostoevsky are hard acts to follow in this minimal con- text, and at times one even starts to long for the movie of Nicholas and Alexandra which at least had a budget and some snow. So we not talking Dr Zhivago here, while from a Les Ms% kind of choral opening the score leaps bizarrely in the second half to a weird kind of Cabaret parody. Neverthe- less, it's all rather interesting in a dark and soulful way, and I for one remain eager to hear what McConnel and Hesketh-Hervey write next; Rasputin maybe needs the full opera, and preferably by Tchaikovsky.

Briefly (in both senses) at the Tricycle, The Snow Palace is not the family Christ- mas outing its title might suggest, but a dark and fascinating new play by Pam Gems about the unpronounceable Polish writer Stanislawa Przbyszewska. She was the author of the Danton eventually filmed by Depardieu; as played hauntingly by Kathryn Pogson, we find her in 1935 alone, morphine-addicted, and living out the early end to her life in the ice-cold wooden but on the estate of the Polish school from which she had recently been expelled as a teacher.

Fingers already numb, refusing any neighbourly offers of food or warmth, Stanislawa is obsessively writing her marathon account of the French Revolu- tion; characters from the period drift in and out of her consciousness and Gems's play, but at the centre is the author herself, determinedly freezing to death as though she were at the North Pole, which is where she might well have been given all the lack of attention she can give to her own reality. When she was found dead, barely as old as the century, just three people went to her funeral; at last, now, she has a public life.

Previous page

Previous page