JASMINE AND THE SOCIAL WORKERS

Roy Kerridge continues his account of

how a child under council care died after horrible injuries

ON THE second day of my appearance at the inquiry into the death of Jasmine Beckford, I was questioned at length. Here are some of the transcripts of my evidence.

Question: Would you look, please, at the second column on page 18 of your article? A. The second column, yes, here we are.

Q. Do you see a little way down from the top there is a sentence which starts, 'A woman who has thankfully given her chil- dren away to the Welfare can expect to have them foisted back on her again if she takes a permanent boyfriend.' A. Yes, correct.

Q. Did you expect people to believe that? A. Yes, because I believe it myself.

Q. Why? A. Well, almost since I left school I have been in the position of almost a Soviet observer, so to speak, someone who tries to fathom the motives of the social services from the outside and to try to make sense of the things they do.

Q. What evidence do you have for that sentence? A. I believe I was thinking of the Maria Colwell case when I wrote that.

Q. Anything else? A. Well, over the years since 1970 I have been writing for a social worker's magazine called New Soci- ety and in it every week there are articles not outlining, but articles concerning the various ideas that social workers have, the various fashions and doctrines which social workers are interested in.

Q. So it is your belief, is it, that as soon as a lady who may for any reason have had the children taken away from her, or had voluntarily to put the children into care, as soon as she finds any boyfriend the social services will simply give the children back? A. Not automatically, but what they often say is that Mrs So-and-So is now part of a united family; she now has a steady, permanent relationship (they say that kind of thing), therefore we feel that bla-bla-bla we will take the child away from the foster parents and return it to her; then the child is usually in these cases returned to the step-father.

Q. Apart from the Maria Colwell case, what other hard evidence do you have to support that statement? A. Well, I haven't any other names to give you, it is just simply my impression but, sir, the doc- trines change over the years. Studying the social services from the outside you can discern a shift in party lines, and shifting movements. For example, now people are far more concerned that children have to be with parents of the same race; they are always concerned with this but lately they are far more concerned.

Q. This article was published on 27 April of this year? A. Yes.

Q. At that time you believed this to be true. I want to know on what evidence? A. I believed what to be, are you saying?

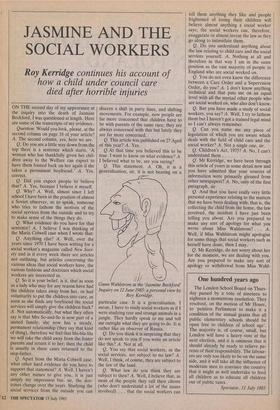

Q. This statement. A. Oh, it is a generalisation, sir, it is not bearing on a Gunn Wahlstrom at the 'Jasmine Beckford' Inquiry on 12 June 1985: a personal view by Roy Kerridge.

particular case. It is a generalisation. I mean, I have to study social workers as if I were studying rare and strange animals in a jungle. They hardly speak to me and tell me outright what they are going to do. It is rather like an observer of Russia.

Q. Do you think it is surprising that they do not speak to you if you write an article like this? A. Not at all.

Q. You say that social workers, or the social services, are subject to no law? A. Well, I think, of course, they are subject to the law of the land.

Q. What law do you think they are subject to then? A. Well, I believe that, as most of the people they call their clients (who don't understand a lot of the issues involved) . . . that the social workers can tell them anything they like and people frightened of losing their children will believe almost anything a social worker says; the social workers can, therefore, exaggerate or almost invent the law as they go along to intimidate them.

Q. Do you understand anything about the law relating to child care and the social services yourself. A. Nothing at all and therefore in that way I am in the same position as the vast majority of people in England who are social worked on.

Q. You do not even know the difference between a Care Order and a Supervision Order, do you? A. I don't know anything technical and that puts me on an equal level with all the myriad other people who are social worked on, who also don't know.

Q. But you have made a study of social workers, you say? A. Well, I try to fathom them but I haven't got a trained legal mind so I can't always remember.

Q. Can you name me any piece of legislation of which you are aware which deals with the field of child care and the social worker? A. Not a single one, sir.

Q. Children's Act, 1975? A. No, I can't understand them. . . .

Q. Mr Kerridge, we have been through this article of yours in some detail now and you have admitted that your sources of information were primarily gleaned from other newspapers? A. No, only of the first paragraph, sir.

Q. And that you have really very little personal experience relating to the matters that we have been dealing with, that is, the collecting the child from the home, the law involved, the incident I have just been telling you about. Are you prepared to make any sort of apology for what you wrote about Miss Wahlstrom? . . . A. Well, if Miss Wahlstrom might apologise for some things that social workers such as herself have done, then I may.

Q. Mr Kerridge, do not worry about her for the moment, we are dealing with you. Are you prepared to make any sort of apology or withdrawal from Miss Wahl- strom? A. Well, I admit that the first few words should not have read 'last March', they should have read 'June 1984'.

Q. That is all you are prepared to apologise for? A. Yes, absolutely.

Q. Why do you dislike Miss Wahlstrom so much? A. Well, I rather dislike Miss Wahlstrom because I had a little boy that I almost looked on as a son and Miss Wahlstrom has taken him away.

The Chairman: Mr Bond, I do not want to stop you if you want to go on. I think we have really had enough from Mr Kerridge.

'Who is responsible for this "Jasmine" case? Why, the press, of course, for blowing it up out of all proportion,' a social worker in the public gallery was heard to remark.

orking in shifts, my relatives and I W have attended all 37 days of the inquiry. Ninety-two witnesses have been called and listened to attentively by Louis Blom- Cooper QC and his independent panel. This is the story that emerges.

Beverley Lorrington gave birth to Jas- mine, her first child, on 3 December 1979. She did not live with Jasmine's father, and later moved in with an old flame and fellow-Jamaican, Maurice Beckford. Jas- mine gained weight normally until she was SIX months old, after which time her weight fell away. The local district nurse advised Beverley about this, assuming, as most district nurses do, that mothers are anxious for their children to thrive. Beckford, meanwhile, had accepted Jasmine as his own child. Soon another girl, Louise, was born to the couple. On 4 August 1981 the Beckfords took Louise to hospital, unable to explain her injuries. The child's arm was broken in two places, spiral fractures that seemed likely to have been caused by someone sharply Pulling and twisting the limbs. Her eyes had been shaken loose from her head. On Monday, Susan Knibbs, the capable middle-aged social worker attached to St Charles's hospital, was called in. She spent the following Tuesday evening interview- ing the Beckfords, and expressed concern over their other daughter, Jasmine. To her amazement, the Beckfords told her that Jasmine was at that moment in another ward in the same hospital. 'I was thunderstruck!' she told the in- quiry panel.

Jasmine had two severe leg fractures. Beverley and Maurice Beckford were later charged with committing the injuries. Neither admitted to breaking bones, but Maurice Beckford supposed that he must have damaged his daughter's eyes by violently shaking her. Not knowing which Of the two was responsible for the other Injuries, the police charged Beckford only With hurting Louise's eyes. A 'case conference' was held on 8 August, called by Miss Knibbs and attended by representatives of all parties concerned with the safety of children, such

as the police and the NSPCC. The two children were put 'in care', which is to say that the Brent council social worker in charge of the case stood in loco parentis to them. This social worker was a newly appointed Swedish girl named Gunn Wahl- strom. On 20 August the hospital arranged yet another case conference to decide the fate of the children. As the Beckfords seemed obviously unsuited to bring up their children, long-term fostering with a view to adoption' was suggested, agreed upon as the best hope for Jasmine and Louise, and written down in the minutes of the meeting. With the full approval of Gunn and everyone else, the two little girls were taken to the home of Peter and Gabriella Probert, the foster parents de- cided upon. The Proberts opened their hearts and home to the two girls, and soon looked forward to the day when they could legally adopt them.

Now, on 4 November 1981, came the trial of that enigmatic man, Maurice Beck- ford. Gunn Wahlstrom, as a witness, sat outside the courtroom for much of the time, and so did not see the horrifying X-rays shown of the children's broken bones. A report on the case, making it clear that the bones had been savagely broken on four separate occasions, was • sent to Brent social services. At the inquiry no one admitted to having seen it or (if they had seen it) to having understood it. Gunn was called in to speak before the magistrate passed sentence on Maurice. She told the court of Maurice Beckford's unhappy childhood, a tale which seemed to have affected her deeply, and this may have influenced the magistrate in his deci- sion to bind Beckford over and release him.

'It is the court's hope that one day this family [the Beckfords and their children] may be rehabilitated,' he stated. This vague pronouncement appears to have been seized on by Brent social work- ers. At the inquiry, I heard the magistrate's remark presented as a positive order for Brent social services to spring into action. All of a sudden, Gunn wrote to Brent Housing Department and arranged for a well-appointed house in Kensal Rise to be provided for the Beckfords. Although Maurice Beckford had a fairly well-paid job with a scaffolding firm, he was given over £300 from the social services purse with which to buy furniture. Previously, the family had lived in a small flat above a shop in the Harrow Road. Another case conference was called, this time by Brent social services, and neither Miss Knibbs, the police, the NSPCC nor the adopting and fostering agencies were informed. It was decided to take the children from the Proberts and return them to Beverley and Maurice Beckford. This notwithstanding a report from Jasmine's doctor expressing surprise at her gain in weight, strength, health and happiness since going to the Proberts.

Before the children could be returned to the Beckfords, 'bonding', as Gunn loves to call it, had to take place, 'monitored' by the social services. At first the Proberts didn't realise what was happening, and merely supposed that no harm could come of Louise and Jasmine visiting their family. Brent's Tree Tops Centre seems to have been a twee place, with a deal of forced heartiness thrown in. Floella Benjamin- like young ladies danced ring-a-rosie with Louise, Jasmine and other children, while Maurice Beckford looked glumly on, sup- posedly learning 'parental skills'. In the kitchen, Beverley learned how to cook English (rather than Jamaican) food. Maurice apparently hated it when the gaudy, decorated Tree Tops van arrived to collect him at his workplace and 'showed him up' in front of his mates.

Next stage in the 'bonding process' was when the children were taken to the Beckfords' house for four hours every week. Then Louise and Jasmine were taken from the Proberts for a short stay at a children's hostel called Green Lodge. Gunn, a 'family aid' worker named Dorothy Ruddock, Beverley and Maurice all visited them each day for 'bonding'. At the inquiry, Gunn agreed that the children had cried every night at Green Lodge, but seemed 'happy' in the daytime. From Green Lodge, in April 1982, the children were taken to the Beckfords' house in Kensal Rise and visited frequently at first by Dorothy Ruddock. The Proberts secret- ly followed the car, found the house in College Road and sat outside it on and off for six months, hoping to see the children. For their pains, they were to be roundly abused by social workers at the inquiry over the death of Jasmine for 'interfering with the bonding process'.

After the brief Tree Tops era, Mr and Mrs Probert had been given a collection of council-made dolls. They had been told to prepare the children for possible 'rehabi- litation' with the Beckfords by showing them two black dolls and two white dolls in one toy house and two black dolls (Maurice and Beverley) in another house.

Then they were supposed to move the first two black dolls to the second dolls' house.

It seems that the Proberts actually did this, and reported that 'the children couldn't understand the game and soon lost in- terest'. The doll idea was later cited appro- vingly at the inquiry as an example of Gunn's 'sensitivity'.

When Jasmine and Louise were taken to Kensal Rise, Mrs Probert wrote a passion- ate letter to Brent social services, saying how fearful she was for their safety. The letter appears to have been filed away and received no reply. However, never for a moment, Mrs Probert testified, did she think Maurice or Beverley would kill one of the girls.

On Gunn's first visit to the Beckfords she seems to have paid far more attention to Maurice Beckford than to the children.

'At first Maurice Beckford seems to have looked on Gunn with suspicion, as she was seen as representing white author- ity,' another social worker on the case, Diane Dietman, told the inquiry. 'This is, of course, an attitude held by all my black clients.'

Gunn appears to have overcome this so-called obstacle. She seems to have been preoccupied with her friendship with Maurice. At another case conference, cal- led by the social workers in November 1982, the children were taken off the Non-Accidental Injuries Register, now 'fully rehabilitated'.

In January 1983, Beverley enrolled Jas- mine at Princess Frederika nursery, but the child hardly attended. As attendance was not compulsory, and no one at the school knew of Jasmine's history, nobody there worried unduly. Gunn claims to have visited the nursery (attached to a school) but no one there remembered having seen her. After one absence, Jasmine arrived at the nursery school with severe bruising. Beverley said that the child had 'fallen off her bike'. In April 1983 Beverley fell pregnant again, and in August of the same year Dorothy Ruddock, the 'family aider', ceased to visit the Beckfords. Gunn made herself useful by driving Beverley to and from hospital for ante-natal inspections, and in December baby Chantelle was born. From then on, all social services to the family were withdrawn, though Gunn thinks she may have had a 'fleeting glimpse' of the children on 22 December. Jasmine's most terrible injuries, the shat- tering of her pelvis and the smashing of her legs in three places, had taken place before that date.

The last time Gunn saw Jasmine was on 12 March 1984. As Gunn had announced her visit in advance, the Beckfords were able to stage-manage events. The children were placed on the floor in a darkened room in front of a video. A bed was placed to obscure Gunn's view of them. After a long chat with Maurice Beckford about repairs needed to the house, Gunn peeped through the door at the children, smiled and then withdrew.

At the inquiry it was suggested to Gunn that she had 'looked at Jasmine, but didn't really see her,' and Gunn replied, 'Yes.' Gunn's main concern appears to have been to have the children taken out of care, and for this purpose she kept paying fruitless visits, knocking at the Beckfords' door to invite them to the review where their consent for this would be necessary. But they didn't answer.

Gunn and her co-worker were anxiously knocking on the door one day in July to tell Maurice about the proposed review. Just then Carol, Beverley's sister, arrived. She had been summoned on the phone by Beverley when it was discovered that Jasmine was dead or dying. Frightened by the sight of two social workers, Carol told them that no one was in. After Gunn and Diane Dietman had gone, Carol came back and took Jasmine's body to the hospital in her car. There it was confirmed that the child was dead. She weighed 23 pounds, two pounds less than when she had left the Proberts two years previously. At least 20 of her bones had been broken during the past year, and her body was a mass of wounds. Not long before Jasmine had been taken from the Proberts, a senior Harrow social worker had complimented the foster parents on the wonderful job they had done. He had been particularly impressed by the improvement in Jasmine's speech and in her recovery from injury.

'I couldn't understand why Maurice didn't answer,' Gunn told the inquiry panel querulously. 'I only wanted to tell him that we were taking the children out of care.'

So much for Jasmine's history. What of the personalities at 'Area Six', or the `Kensal Rise Patch', the social services team in charge of the inhabitants or would- be 'clients'? One of them, Mr Bishop, 'manager of Area Six', admitted Tippexing over the phrase 'long-term fostering with view to adoption' on the case conference minutes of August 1981. He substituted the words 'short-term fostering' in every case.

A brash young man with a ruffianly, unshaven grin and a brush-like quiff of hair, he resembled a Teddy boy who had outgrown his gang and now spent his time standing portentously in the local pub shouting 'No way was that player offside!' He explained his Tippexing habits by

'And the princess got out of the car,this time wearing a red wig . . .

saying that the minutes may have been copied wrong, were not an accurate reflec- tion of what was said, and needed 'correc- tion'.

'But Mr Bishop,' rumbled old Blom- Cooper, 'the minutes of a meeting ought to be an accurate account of what was said, and not to be "corrected".'

'Point taken,' said Bishop crisply, and there the matter was allowed to rest.

Blom-Cooper seemed to have a soft spot for Bishop, and sometimes adjourned the hearing at a tricky point of cross- examination seemingly to allow the young man to think. Mr Bishop's thoughts seemed preoccupied by computer games, for he described human activity in terms of 'input', 'output' and 'feedback'.

'This was seen as a promotion-testing case for Gunn,' he told the inquiry panel.

It seems obvious that Gunn sought to advance herself by strictly following the party line (or 'guidelines') on keeping black children in black homes. But who lays down this line in the first place? It is still a mystery. Bishop, who has enjoyed his present post since 1976, went on to describe the difficulties of working in a 'deprived area', seemingly defined as one where coloured people live.

'We had some questions on the Afro- Caribbeans at first,' he said. 'For instance, do they speak English?'

This was not quite as tactless as Gunn Wahlstrom's remarks when at last she was called upon to speak. Her confidence shaken at first, Gunn took her seat in the witness chair and answered her own coun- sel, Mt Bond, when he asked about her training and post-training experience.

'Were you afraid of Maurice Beckford?' he inquired.

'No, I was not,' she replied with a touch of scorn, and launched again into an account of the man's childhood. 'Maurice enjoyed being in care as a child — he preferred it to living with a family. When he was nine, he went to Woodfield School for the Educationally Subnormal. That was not unusual that time, as they didn't fit into the educational system. The educational system was different then, and didn't cater for them. Not that they are subnormal in any way.'

Here she looked unconcernedly around at the many learned West Indian barristers on the panel, who looked impassively back.

The inquiry has now adjourned until September, ending in a welter of 'black experts', all insisting, to no opposition, that black children must always be fostered with black families. One expert, David Divine, gave a ferociously militant speech and then told the Proberts' counsel that if one parent were black that constituted 'a black family'. This ruling would have qualified the Proberts to foster Jasmine and Louise, as Mr Probert is of part-Indian descent. With such meagre crumbs of hope for the future, I too must wait until September, when Blom-Cooper hopes to sum up the case in his way and I in mine.

Previous page

Previous page