The centre that could not hold

FROM ROME TO BYZANTIUM: THE FIFTH CENTURY AD by Michael Grant Routledge, £25, pp. 203 Roman history begins in Rome and ends at Constantinople.' It recounts the slow shift of the centre of gravity of the Mediterranean world — of European civili- sation — from a pagan, latin West to a Christian, hellenised East. Here it will remain, until northern Europe asserts itself in the High Middle Ages.

This epic found its Homer in Gibbon. But it contains no more fascinating passage than the fifth century, the subject of the latest in a long, distinguished series of pop- ular, scholarly works by Michael Grant. This one, however, may not entice to the end a reader not already interested in late Antiquity: the style is clumsy; there are massive quotations from secondary sources; the organisation and flow found in fellow historians of the period such as Peter Brown, Averil Cameron — or earlier Grant — are missing.

Some episodes of special interest to readers in these islands do not feature either: the departure, for instance, of Roman forces from Britain around 407, or the later resistance to the invading Saxons by the mysterious Ambrosius Aurelianus, who may perhaps represent any reality there is behind King Arthur. The set pieces, however, are here: the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410; the extinc- tion of the Western Empire by the compul- sory redundancy, with pension, of the last, insignificant emperor, Romulus Augustu- lus, in 476 . . .

The impact of that sack lay in its symbol- ism — Rome, despite its prestige, was no longer the actual capital. But Jerome still howled from his retreat in Palestine that `the bright light of the world was quenched . . . the whole Universe had perished in one city'. Of more enduring importance for Western thought, it forced Augustine to address the tormenting question of how could God permit such a catastrophe when Rome was a Christian city? His answer was The City of God, finished in 427. Here, he argues that paganism was in error; that Christianity was no guarantee of earthly happiness; and, with grim consequences for the future, that man is inherently sinful and in desperate need of divine grace for forgiveness. (He had no time for the British 'heretic' Pelagius, who emphasised our freedom to choose.) But why, Grant asks, were all these disas- ters happening? Why should the Western Empire 'fall', but the Eastern Empire go on, in the next century, to produce St Sophia and attempt the reconquest of the Mediterranean basin, and indeed survive till 1453? There seem almost as many explanations as historians, despite an emerging consensus that general theories, applying equally to the East, are suspect. Of these, the best known is Gibbon's: 'bar- barians', an otherworldly Church and a decay of civic spirit were to blame. More recent writers, without writing off the Ger- man invaders, concentrate on structural factors: in the West, a more military gov- ernment, and a super-rich senatorial class that would neither provide soldiers from their estates nor cash, had neither the skill nor resources to survive; in the East, more effective administration, a stronger economy, the resources of Asia Minor, a more civic-minded and less rich senatorial class, and the impregnable walls of Constantinople saved the day.

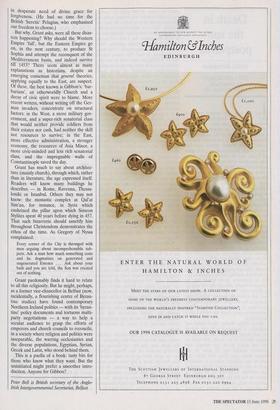

Grant has much to say about architec- ture (mainly church), through which, rather than in literature, the age expressed itself. Readers will know many buildings he describes — in Rome, Ravenna, Thessa- loniki or Istanbul. Others they may not know: the monastic complex at Qal'at Sim'an, for instance, in Syria which enshrined the pillar upon which Simeon Stylites spent 40 years before dying in 457. That such bizarrerie should sanctify him throughout Christendom demonstrates the ethos of the time. As Gregory of Nyssa complained:

Every corner of the City is thronged with men arguing about incomprehensible sub- jects. Ask a man how much something costs and he dogmatises on generated and ungenerated Essence ... Ask about your bath and you are told, the Son was created out of nothing.

Grant pardonably finds it hard to relate to all this religiosity. But he might, perhaps, as a former vice-chancellor in Belfast (now, incidentally, a flourishing centre of Byzan- tine studies) have found contemporary Northern Ireland politics — with its 'byzan- tine' policy documents and tortuous multi- party negotiations — a way to help a secular audience to grasp the efforts of emperors and church councils to reconcile, in a society where religion and politics were inseparable, the warring ecclesiastics and the diverse populations, Egyptian, Syrian, Greek and Latin, who stood behind them.

This is a paella of a book: tasty bits for those who know what they want. But the uninitiated might prefer a smoother intro- duction. Anyone for Gibbon?

Peter Bell is British secretary of the Anglo- Irish Intergovernmental Secretariat, Belfast.

Previous page

Previous page