False dreams

Charles Spencer

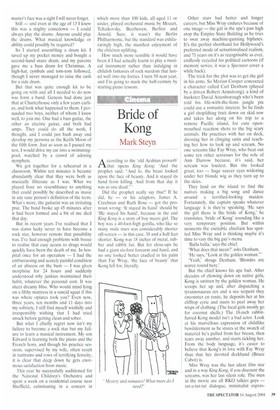

Elor several decades I possessed only one firm article of faith. It was the conviction that whatever else one might achieve in life, nothing could ever offer adequate compensation for failing to become a rock star. As soon as I saw Mick Jagger on Top of the Pops at the age of nine I knew that one day I wanted to be just like him. Then I heard Eric Clapton playing with Cream, and realised that if I failed to make it as a frontman, being a guitar god would be pretty cool, too.

The one snag in all this was a complete lack of musical ability. My parents never bullied me into learning an instrument as a child, and when I was auditioned for the choir at Charterhouse, as all 'New Hops' were, the expression of pain on the music master's face was a sight I will never forget.

Still — and even at the age of 13 I knew this was a mighty comedown — I could always play the drums. Anyone could play the drums. What musical knowledge or ability could possibly be required?

So I started assembling a drum kit. I saved up my pocket money and bought a second-hand snare drum, and my parents gave me a bass drum for Christmas. A high-hat, cymbals and tom-tom followed, though I never managed to raise the cash for a side drum.

But that was quite enough kit to be going on with and all I needed to do now was form a band. Genesis had done just that at Charterhouse only a few years earlier, and look what happened to them. I persuaded two boys, neither of whom I knew well, to join me. One had a bass guitar, the other an electric guitar, and both had amps. They could do all the work, I thought, and I could just bash away and develop my persona as the Keith Moon of the fifth form. Just as soon as I passed my test, I would drive my car into a swimmingpool, watched by a crowd of adoring nymphets.

We got together for a rehearsal in a classroom. Within ten minutes it became abundantly clear that they were both as musically illiterate as I was. What we played bore no resemblance to anything that could possibly be described as music in any sane person's definition of the term. What's more, the guitarist was an irritating prat. The band broke up 45 minutes after it had been formed and a bit of me died that day.

But in recent years I've realised that I was damn lucky never to have become a rock star, however remote that possibility was. I've had enough problems with booze to realise that easy access to drugs would quickly have been the death of me. In hospital once for an operation — I had the embarrassing and acutely painful condition of an abscess on the bum — I was given morphine for 24 hours and suddenly understood why junkies maintained their habit, whatever the personal cost. It was sheer dreamy bliss. Who would mind lying on a filthy mattress in a rancid squat if this was where opiates took you? Even now, three years, ten months and 11 days into my sobriety. I still find myself wistfully and irresponsibly wishing that I had tried smack before getting clean and sober.

But what I chiefly regret now isn't my failure to become a rock star but my failure to learn a musical instrument. My son Edward is learning both the piano and the French horn, and though his practice sessions, supervised by my wife, often result in tantrums and rows of terrifying ferocity, it is clear that deep down he gets enormous satisfaction from music.

This year he successfully auditioned for the National Children's Orchestra and spent a week on a residential course near Sheffield, culminating in a concert in which more than 100 kids, all aged 11 or under, played orchestral music by Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Berlioz and Arnold. Sure, it wasn't the Berlin Philharmonic, but the standard was exhilaratingly high, the manifest enjoyment of the children uplifting.

How much more sensible it would have been if I had actually learnt to play a musical instrument rather than indulging in childish fantasies of rock stardom that lasted well into my forties, I turn 50 next year, and I'm going to mark the half-century by starting piano lessons.

Previous page

Previous page