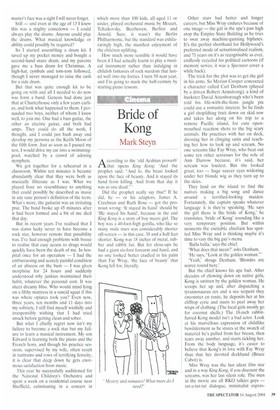

Bride of Kong

Mark Steyn

According to the 'old Arabian proverb' that opens King Kong: ' And the prophet said: "And lo, the beast looked upon the face of beauty. And it stayed its hand from killing. And from that day it was as one dead."' Did the prophet really say that? If he did. he — or his adaptors, James A. Creelman and Ruth Rose — got the pronoun wrong: 'It stayed its hand' should be 'He stayed his hand', because in the end King Kong is a story of boy meets girl. The boy was a 40-foot-high gorilla, who like so many male stars was considerably shorter off-screen — in this case, 38 and a half feet shorter. Kong was 18 inches of metal, rubber and rabbit fur. But for close-ups he had a giant six-foot forearm and hand, and no one looked better cradled in his palm than Fay Wray, 'the face of beauty' that Kong fell for, literally.

Other stars had better and longer careers, but Miss Wray endures because of one image — the girl in the ape's paw high atop the Empire State Building as he tries to swat away machine-gunning biplanes. It's the perfect shorthand for Hollywood's preferred mode of sensationalised realism, and 71 years on it's as recognisable as ever, endlessly recycled for political cartoons (if memory serves, it was a Spectator cover a while back).

The trick for the plot was to get the girl in his arms. So Merian Cooper concocted a character called Carl Denham (played by a driven Robert Armstrong), a kind of huckster David Attenborough who's been told his life-with-the-lions jungle pix could use a romantic interest. So he finds a girl shoplifting fruit down on skid row and takes her along on his trip to a remote Pacific island, for cute openmouthed reaction shots to the big scary animals. He practises with her on deck, dressing her in clinging satin and teaching her how to look up and scream. No one screams like fay Wray, who beat out some ten other actresses for the role of Ann Darrow because, it's said, her scream was loudest. But she looked great, too — huge saucer eyes widening under her blonde wig as they turn up to the skies.

They land on the island to find the natives making a big song and dance around a terrified-looking maiden. Fortunately, the captain speaks whatever language it is they're speaking. 'He says the girl there is the bride of Kong,' he translates, 'bride of Kong' sounding like a very temporary position. But within moments the excitable chieftain has spotted Miss Wray and is thinking maybe it's time to vary the big guy's menu.

'Balla balla,' says the chief.

'What does that mean?' asks Denham. 'He says, "Look at the golden woman."' 'Yeah,' shrugs Denham. 'Blondes are scarce round here.'

But the chief knows his ape bait. After decades of chowing down on native girls, Kong is smitten by the golden woman. He scoops her up and, after dispatching a tyrannosaurus rex and a sea serpent they encounter en route, he deposits her at his elifftop eyrie and starts to peel away her wisps of clothing. (The local girls mostly go for coconut shells.) The 18-inch rabbitfurred Kong model isn't a bad actor, Look at his marvellous expression of childlike bewilderment as he stares at the swatch of material he's pulled from her breast, then tears away another, and starts tickling her. From the body language, it's easier to believe that Kong's in love with Fay Wray than that her devoted cleckhand (Bruce Cabot) is.

Miss Wray was the last silent film star and in a way King Kong, if you discount the screams, was her last silent role. The men in the movie are all RKO talkies guys — rat-a-tat-tat dialogue, minimalist expres sions — but their girl is all 'Nefertiti eyes' (as someone called them back in the Twenties) and heavy indicating and a head permanently in motion. She's lovely — and in one shipboard scene appears to be braless under a very revealing dress — but she seems, even in 1933, to belong to the old days. She was 26 and had been a working movie actress for a decade, since her first role in the 1923 comedy short Gasoline Love. She was in some classic silents (Erich von Stroheim's Wedding March) and a lot of forgettable ones, just as she was in some good talkies (The Bowery) and a lot of forgettable ones, including a slew of postKong duds made in England. She more or less retired from movies in 1958, though directors were always trying to lure her back.

Born in Alberta, raised in Arizona and Utah, and sent at the age of 14 to live with a male friend of her sister's in Hollywood, Fay Wray had no reason to wind up a movie star other than her own determination: she was good-looking in the way the gal serving you hash in the greasy spoon back in Arizona might be. She was a smart, largely self-taught woman who loved writers. Between them, her husbands and lovers wrote the screenplays of Wings, The Dawn Patrol, It Happened One Night, Lost Horizon, You Can't Take It With You, Golden Boy, The Big Knife and Rhapsody in Blue. After acting. Miss Wray turned to playwriting herself — her last work was premiered in New Hampshire a few years back — and also came up with a very beguiling memoir with a Kong-alluding title, On the Other Hand.

They wanted her for a cameo in the Seventies remake of Kong, but she didn't care for the script, and she was right. In my disc-jockey days, I shared an office with a guy who had a still from the new Kong pinned to the wall, showing Jessica Lange in the ape's paw with a Janet Jackson-style wardrobe malfunction and her nipple sticking out. It seemed a million times less erotic than Miss Wray's bare shoulders wiggling under Kong's hairy thumb four decades earlier. Now Peter Jackson, free of Lord of the Rings, is making another version, perhaps in an attempt to put the number of King Kongs closer to those of its near namesake King Dong. Jackson offered Miss Wray the closing line of the movie, a reprise of what was used by Robert Armstrong 70 years ago: "Twas beauty killed the beast.' But Miss Wray again demurred.

Did they know how special the original was? It saved RKO from bankruptcy, and started a genre — the movie monster that spawned all the others. On Tuesday evening, in acknowledgment of Fay Wray's passing, the Empire State Building dimmed its famous spire. But in the iconography of popular culture she'll always be up there, the beauty trembling on a ledge as a bleeding, dying beast reaches out to touch her one last time.

Previous page

Previous page