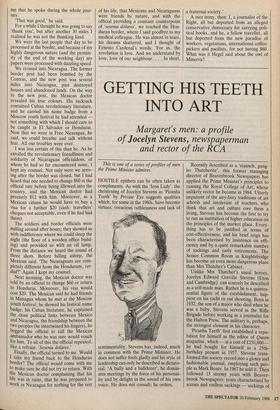

GETTING HIS TEETH INTO ART

Margaret's men: a profile

of Jocelyn Stevens, newspaperman

and rector of the RCA

This is one of a series of profiles of men the Prime Minister admires.

HOSTILE epithets can be often taken as compliments. As with the 'Iron Lady', the christening of Jocelyn Stevens as 'Piranha Teeth' by Private Eye suggests qualities which, for some in the 1980s, have become virtues: voracious ruthlessness and lack of sentimentality. Stevens has, indeed, much in common with the Prime Minister. He does not suffer fools gladly and his style of leadership can only be described as dictato- rial. 'A bully and a bulldozer', he domin- ates meetings by the force of his personal- ity and by delight in the sound of his own voice. He does not consult; he orders. Recently described as a 'staunch, gung- ho Thatcherite', this former managing director of Beaverbrook Newspapers has applied the Prime Minister's principles to running the Royal College of Art, whose unlikely rector he became in 1984. Utterly impatient of the airy-fairy traditions of art schools and intolerant of teachers who think that art and culture owe them a living, Stevens has become the first to try to run an institution of higher education on the principles of the market place. Every- thing has to be justified in terms of cost-effectiveness, and his brief reign has been characterised by insistence on effi- ciency and by a quite remarkable number of sackings and early retirements. The Senior Common Room in Knightsbridge has become an even more dangerous place than Mrs Thatcher's Cabinet.

Unlike Mrs Thatcher's usual heroes, Jocelyn Edward Greville Stevens (Eton and Cambridge) can scarcely be described as a self-made man. Rather he is a quintes- sential figure of the establishment, hap- piest on his yacht or out shooting. Born in 1932, the son of a major who died when he was a baby, Stevens served in the Rifle Brigade before working as a journalist for the Hulton Press. The military is, perhaps, the strongest element in his character.

`Piranha Teeth' first established a repu- tation for himself as the editor of Queen magazine, which — at a cost of £250,000 he had bought for himself as a 25th- birthday present in 1957. Stevens trans- formed this society record into a glossy and fashionable journal, employing such peo- ple as Mark Boxer. In 1967 he sold it. Then followed 15 stormy years with Beaver- brook Newspapers: years characterised by scenes and endless sackings — sackings of editors of the Daily Express and Evening Standard almost too numerous to count; mass sackings of Beaverbrook employees in Scotland and elsewhere. All this bullying culminated in Stevens's own sacking in 1982 by what had become the Express Group.

When Stevens was appointed Rector of the RCA, he was virtually unemployed. The dynamic businessman had reverted to his youth and was running another fashion- able glossy in the shape of The Magazine. The chairman of the governors who approached Stevens was the late Lord Howard, but the honour of fixing this appointment has been claimed by John Hedgecoe, the Professor of Photography at the RCA.

Stevens and Hedgecoe are now known by some in the College as the `Kray Twins'. The reforms have been nothing if not cold and ruthless: 14 out of 17 professors have left — to date — since Stevens arrived, some of them having been appointed by the new rector himself. Three of the college's 16 departments have been closed, and more — notably Architecture — are threatened. Stevens regards himself as a decision-maker; the decisions have been many, and final.

What is beyond dispute is that the RCA was in as parlous a state in 1984 as the British economy was when Mrs Thatcher became prime minister. Unseemly internal rows, culminating in the sacking of the rector — Lionel March, the prophet of computer design in architecture — had led to general demoralisation and the real threat of cuts in grants from the Depart- ment of Education and Science. Stevens immediately set about cutting out `dead wood', that is, almost every employee who preceded his advent, and tried to put the college on a sound economic basis, so restoring the confidence of the DES in the institution.

The conventional idea of an art college has been overturned. Students are no longer encouraged merely to be `artists' but to be commercially useful. `A master's degree student who can get a job only as a waitress is a failure, a failure on our part because we've wasted that person's time and we've wasted tax-payers' money', Steven has been quoted as saying. To save tax-payers' money, student courses have been cut from three years to two. Courses which have a clear commercial application, like industrial design or fabric design, have been encouraged.

Perhaps only Stevens could have done this. His strength is that he is an outsider. Conspicuous amidst all the denim and corduroy by his dark suits and striped shirts, he enjoys the confidence of civil servants in a way that no frustrated artist could. Ministers see him as one of them- selves. This has been reflected in his getting some f10 million out of the tight- fisted DES to create a new display gallery on the hitherto under-used ground floor and for a general refurbishment of the dark grey 1960s concrete building.

Buildings and space have been rational- ised. By selling off college hostels and leaseholds, Stevens has displayed his ta- lents as a Thatcherite asset stripper. Opin- ions differ on the success of his manage- ment. While it is true that the rector has obtained computers and other gifts in kind from industry, there has been less cash from the private sector. And although Stevens may well have close contacts in the `real' world of business and banking, he has also succeeded in making many ene- mies over the years by the unpleasantness of his behaviour.

Without any real understanding of the virtues of academic life, Stevens has — like the Prime Minister — conventional tastes in art. (The most unconventional thing about him is his living in Chelsea with Mrs Vivian Duffield, the daughter of the late Sir Charles Clore — `She's even richer than I am,' Private Eye quoted him as saying in 1977.) He can easily descend into vulgar- ity. Staff squirm with embarrassment at the gaudy writing paper he chose for the college (and which he himself does not use). Much more serious, however, is the atmosphere he has created in the college. It is one of uncertainty, if not fear. The energies of staff are devoted to survival rather than the future and Stevens's bul- lying manner and unpredictable character makes it very different for him to elicit support and enthusiasm. Apart from his delight in hiring and firing, the principal liability is the rector's uncontrollable tem- per. This is legendary from his newspaper days: the occasion when he sacked every- one over the intercom; the time he threw a telephone console through an internal glass partitition; the unfortunate man at Queen who was shaken so violently that the money came out of his pockets. Those who have experienced these rages all testify to how absolutely frightening they are. But perhaps they help in getting things done.

Jocelyn Stevens promises that his reign of terrors will definitely come to an end in 1989 when his five-year contract expires. What then? Now that he has shown that the arts, like everything else, can be run on the lines of a business, no matter at what sacrifice, perhaps the Iron Lady will find a suitable use for `Piranha Teeth's' energy and rage.

Previous page

Previous page