ARTS

Photography

Roger Fenton (Hayward Gallery, till 17 April)

Master of light

Francis Hodgson

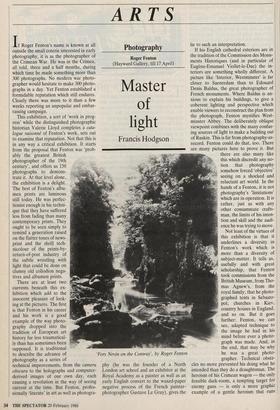

If Roger Fenton's name is known at all outside the small coterie interested in early photography, it is as the photographer of the Crimean War. He was in the Crimea, all told, three and a half months, during which time he made something more than 300 photographs. No modern war photo- grapher would hesitate to make 300 photo- graphs in a day. Yet Fenton established a formidable reputation which still endures. Clearly there was more to it than a few weeks reporting an unpopular and embar- rassing campaign. Fors Nevin on the Conway', by Roger Fenton phy (he was the founder of a North London art school and an exhibitor at the Royal Academy as a painter as well as an early English convert to the waxed-paper negative process of the French painter- photographer Gustave Le Gray), gives the lie to such an interpretation.

If his English cathedral exteriors are in the tradition of the Commission des Monu- ments Historiques (and in particular of Eugene-Emanuel Viollet-le-Duc) the in- teriors are something wholly different. A picture like 'Interior, Westminster' is far closer to Saenredam than to Edouard Denis Baldus, the great photographer of French monuments. Where Baldus is an- xious to explain his buildings, to give a coherent lighting and perspective which enable viewers to reconstruct the plan from the photograph, Fenton mystifies West- minster Abbey. The deliberately oblique viewpoint combines with the many confus- ing sources of light to make a building out of Ruskin. This is far from photography-as- record. Fenton could do that, too. There are many pictures here to prove it. But there are also many like this which discredit any no- tion that photography somehow forced 'objective' seeing on a shocked and reluctant art world. In the hands of a Fenton, it is not photography's 'limitations' which are in operation. It is rather, just as with any other consummate crafts- man, the limits of his inten- tion and skill and the audi- ence he was trying to move.

Not least of the virtues of this exhibition is that it underlines a diversity in Fenton's work which is more than a diversity of subject-matter. It tells us, usefully and with great scholarship, that Fenton took commissions from the British Museum, from Tho- mas Agnew's, from the royal family; that he photo- graphed tents in Sebasto- pol, churches in Kiev, country houses in England, and so on. But it goes further: Fenton, we can see, adapted technique to the image he had in his mind before ever a photo- graph was made. And, in the end, that may be why he was a great photo- grapher. Technical obsta- cles no more prevented his doing what he intended than they do a draughtsman. The heroism of his Crimean wagon — the only feasible dark-room, a tempting target for enemy guns — is only a more graphic example of a gentle heroism that runs throughout his career, that of ensuring that photographic rightness was only a pre- liminary to artistic rightness, not a replace- ment for it.

The second undercurrent is about pre- cisely that, Fenton's career. He was a photographer for only ten years. The grandson- of a Lancashire mill-owner and son of a Whig MP for Rochdale, he might have been an amateur like Lady Hawar- den. In fact he was not. He seems to have been serious about photography in a way that can only be described as professional — scrupulous about contracts, thorough about technique, and determined as a publicist for photography. He was the Prime mover behind the foundation of what was to become the Royal Photo- graphic Society, and its first Secretary, an administrator and populariser as well as a practitioner.

In all this we get a picture of a deter- mined and successful Victorian entre- preneur, averse neither to a little tactful self-publicity (it was he who accompanied the royal party around the first Royal Society Exhibition of Photographs and Daguerreotypes in 1854; the royal portraits that ensued' can have done his career no harm). nor to solid commercial dealings. He was sent to the Crimea, after all, by a print dealer, unlike the celebrated corres- pondent William Howard Russell, who was sent by the Times. His attitude to photo- graphy was like that of Dr Grace to cricket — they both knew they were good and, professional to their fingertips, had no qualms about abandoning previous amateurishness for solid success.

This is a curious exhibition for several reasons. Here are several of what must be the earliest portraits of posed groups in which some of the sitters have their back to the camera. The scrupulous objectivity of the reproductions of works of art sits a little uneasily with the lush, Lorrian- derived vision of the English landscape. This diversity is a tribute to Fenton, of course. But it also drives home a simple point. Even at his most bald, in `Saltash Bridge Under Construction', say, or in the delightful `Vivandiere' from the Crimea, Fenton is using his skill as a marshal of light and composition to make us see what he wants, and not merely what was there. Rarely has an exhibition more graphically demonstrated that photography is no more objective than any other means of setting down one's vision. Fenton's photography is never simple. Less than 20 years after the invention of photography he was in perfect control not only of apparatus and process but also of the tremendous potential alliance photography offered between sub- jective and objective, between images seen and sights imagined. There are many real masterpieces here: of reporting, of imagining, just of seeing. `Fors Nevin on the Conway' must stand for them all, magically conjured from a few gleams, some shadows, haze, reflection, almost nothing. Fenton was that kind of photographer. Somebody who could make something out of nothing. And his philo- sopher's stone? Light, pure light.

Previous page

Previous page