The castle of Poland

Timothy Garton Ash

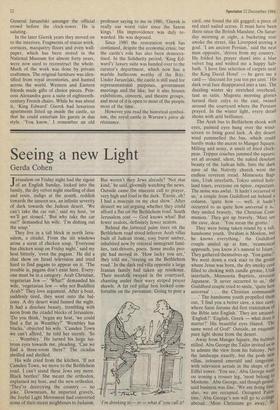

Earlier this year, Poland's royal castle was ceremonially opened to the pub- lic. 'We have tried to reconstruct it as it was in the time of our last king, explained my guide, as we walked through the glittering state rooms, with their new par- quet floors and acres of bright gilding. 'Our last king' was, of course, Stanislaus Augus- tus — 'poor, foolish Poniatowski,' as Car- lyle so unfairly described him, 'an empty, windy creature, redolent of macassar.' In fact, Poniatowski, though initially a Rus- sian client, did his best to revive and reform the old Polish Commonwealth, against the designs of its predatory super- power neighbours. It was not the King's fault alone that his reign ended with the complete destruction of his kingdom in the Third Partition of 1795. Indeed, the state rooms as we see them today were intended by Stanislaus Augustus to symbolise and encourage the renascence of Polish nation- al pride. Here, first, are his immediate predeces- sors, the despicable, fat-faced Saxon kings, sneering down from portraits 'given by East Germany' — as my guide says, with a significant sigh. Here is the Canaletto room, with its splendid tableau of the Royal Election in 1764: the-noble electors gathered under their regional standards on the Wola field near Warsaw (Wola is now a borough of heavy industry, its factories Solidarity strongholds), the dumpy Pri- mate, the Voivods and the Marshal of the sejm. The only people Canaletto's painting does not show are the Russian soldiers who surround the field to ensure the election of Moscow's candidate. And here is Mate- jko's great, melodramatic picture of 'Re- `50p to play this video of us singing a carol.' jtan's defiance'. Tadeusz Rejtan was an envoy to the sejm who begged his fellow parliamentarians to resist the First Parti- tion, rending his clothes and saying, 'On the blood of Christ . . . do not play the part of Judas; kill me, stamp on me, but do not kill the fatherland.' One of Warsaw's livelier grammar schools now bears his name. During the Pope's mass (or rather Mass) meeting in Warsaw last year, its pupils held aloft a large banner. It said simply 'Rejtan' — in red, jumbly lettering on a white ground.

So the history lesson goes on — through the King's private conference room, where George III hangs next to Frederick and Catherine the Great (whom they've put in front of a large mirror, to satisfy her famous vanity);through the Knights' Hall, with Jan Sobieski marching towards Vien- na; the Senator's Hall, where parliament used to meet and the 3 May 1791 constitu- tion was proclaimed — a gesture of liberal reform to which the superpowers re- sponded with the Second Partition; and on to the former chapel which now displays, in a black casket, the heart of Tadeusz Ko§ciuszko, leader of the 1794 National Rising which ended in the Third and final Partition (`And Freedom shrieked as Kog- ciuszko fell'). On the wall of the Senators' Hall they have painted a map of Poland as it was under 'our last King' — stretching deep into the Soviet Union:

Of course, one can draw various conclu- sions from this history. Poland's current rulers would have the castle bearing wit- ness to the tradition of Polish statehood from Poniatowski to Jaruzelski, so to speak. The story of the reconstruction is a history lesson in itself. At the end of the war the castle was a mound of rubble: what their bombs had not destroyed in Septem- ber 1939, the Germans systematically flat- tened after the Warsaw Rising. The Old Town was rebuilt all around it, but the castle remained an open space. Only in 1971 did the new Party leader decide that it, too, should be restored. Gierek meant it to symbolise the restoration of patriotic unity, after the strikes and the bloodshed on the Baltic coast. The legitimacy of communist rule in Poland would be rebuilt brick by brick with the royal castle. A `Citizens' Committee' was formed, with people from (as they say) `all walks of life'. A great deal of money was collected from ordinary citizens — and some $800,000 from Poles abroad. Building work pro- ceeded apace. At 11.15 am on 17 Septem- ber 1974 the main clock, which had been stopped by a German bomb at that hour on that day in 1939, was solemnly restarted. Photographs show a much younger looking

General Jaruzelski amongst the official crowd before the clock-tower. He is saluting.

In the later Gierek years they moved on to the interiors. Fragments of stucco work, cornices, marquetry floors and even wall- paper, which has been stored in the National Museum for almost forty years, were now used to reconstruct the whole. Much of the work was done by private craftsmen. The original furniture was iden- tified from royal inventories, and hunted across the world. Western and Eastern friends made gifts of choice pieces. Prin- cess Alexandra gave a suite of eighteenth- century French chairs. While he was about it, 'King Edward' Gierek had luxurious apartments fitted up inside the castle, so that he could entertain his guests in due style. 'You know,' I remember an old professor saying to me in 1980, `Gierek is really our worst ruler since the Saxon kings.' His improvidence was duly re- warded. He was deposed.

Since 1980 the restoration work has continued, despite the economic crisis; but the castle's role has also been democra- tised. In the Solidarity period, 'King Ed- ward's' luxury suite was handed over to the curator's department, which now has a marble bathroom worthy of the Ritz. Under Jaruzelski, the castle is still used for representational purposes, government meetings and the like; but it also houses exhibitions, concerts, and theatre groups, and most of it is open to most of the people most of the time.

However you read the historical symbol- ism, the royal castle is Warsaw's piece de resistance.

Previous page

Previous page