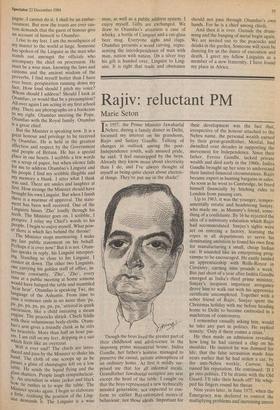

Rajiv: reluctant PM

Marie Seton

In 1957, the Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, during a family dinner in Delhi, focussed my interest on his grandsons, Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi. Talking of changes in outlook among the post- Independence youth, with amused pride, he said: 'I feel outstripped by the boys. Already they know more about electricity thah I do, and I've always thought of myself as being quite clever about electric- al things. They've put me in the shade!'

Though the boys lived the greater part of their childhood and adolescence in the imposing prime ministerial house, Indira Gandhi, her father's hostess, managed to preserve the casual, private atmosphere of an ordinary home. At first it mildly sur- prised me that for all informal meals, Grandfather Jawaharlal occupied any seat except the head of the table. I caught on that the boys represented a new technically minded generation, not expected to con- form to earlier Raj-orientated mores of behaviour, nor those ideals. Important for their development was the fact that, irrespective of the honour attached to the Nehru name, the personal wealth earned by their great-grandfather, Motilal, had dwindled over decades in supporting the movement for Independence. Since their father, Feroze Gandhi, lacked private wealth and died early in the 1960s, Indira Gandhi brought up her sons to understand their limited financial circumstances. Rajiv became expert in hunting bargains in sales. As soon as he went to Cambridge, he freed himself financially by hitching rides to London from passing cars.

Up to 1963, it was the younger, temper- amentally erratic and headstrong Sanjay, who made me, as Mummy's friend, some- thing of a confidante. By 16 he rejected the idea of a university education which Rajiv had accommodated. Sanjay's sights were set on entering a factory, learning the ropes in all departments to serve his dominating ambition to found his own firm for manufacturing a small, cheap Indian car. It sounded like an enterprising prog- ramme to be encouraged. He easily landed an apprenticeship with Rolls-Royce in Coventry, earning nine pounds a week. But just short of a year after Indira Gandhi emerged as India's third prime minister, Sanjay's incipient impatient arrogance drove him to walk out with his apprentice certificate uncompleted. Together with a sober friend of Rajiv, Sanjay spent the Christmas holiday with me before heading home to Delhi to become embroiled in a maelstrom .of controversy.

I remember casually asking him, would he take any part in politics. He replied tensely: 'Only if there comes a crisis.'

He then made an admission revealing how long he had carried a chip on his shoulder. He insisted he was damned for life; that the false accusation made four years earlier that he had stolen a car, by the anti-Nehru weekly, Current, had ruined his reputation. He continued: `If I go into politics, I'll be drastic with the Old Guard. I'll take their heads off!' He whip- ped his fingers round his throat.

Nine years later, in June 1975, when the Emergency was declared to control the multiplying problems and increasing unrest played up by an irresponsible opposition, Sanjay Gandhi carried out his threat with draconian actions. The result at the next 1977 election brought defeat to Indira Gandhi and the installation of an incompe- tent coalition government which did little but wage internecine war which damaged the hitherto stable, if imperfect, Indian socio-political balance. By 1980, the voters turned back to Mrs Gandhi, deciding there was no better alternative leader. By then, Sanjay through reckless flying tricks in a plane he'd been warned was unsuitable, had crashed to his death in the centre of Delhi.

I have little doubt that Sanjay's destruc- tive daemon was roused by the shock of his father, Feroze's death, and fanned by the too young ambitiously pert Menaka Anand whom he married and brought into Indira Gandhi's house. The climax of Menaka's animus is that in the current election, she is standing against her brother-in-law, Rajiv, in his constituency of Amethi.

Except in fiction, there couldn't be two brothers of greater difference in character than the Gandhi boys.

Rajiv, singularly domestically inclined, came from Cambridge to stay with his mother and me in the summer of 1963 in my Kensington flat. It was in a chaotic mess since I'd only returned from four years in India a couple of days before. Still Rajiv happily tucked himself up on the floor beside Indira's bed. So that mother and son could be on their own, I went to visit a friend and stayed overnight. Return- ing, I found that working together, Indira and Rajiv had reorganised and abolished the mess, transforming my flat into a pleasantly habitable place. No other friends ever did me such an unexpected kindness. When Indira went back to Paris to complete her work at Unesco, I gave Rajiv a key to my flat to come and go as suited him. For the next three years he proved his prudent reliability and practical ways of being helpful. He liked to come and cook over weekends. He came to parties, volunteering to undertake the messy and boring chores.

When he moved from Cambridge to the Imperial College near me, his concern was not to fail. I insisted that it seemed unlikely that his grandfather, Nehru, would have done as well as he did except for the nagging of his father, Motilal. As I was working on my biography of Jawahar- lal Nehru, I asked Rajiv to help in checking the galley proofs. He did a carefully competent job. Soon after he started, he surprised me by saying that he'd never before realised the family role nor that of the Congress Party, in the Independence struggle.

In Cambridge, Rajiv had met a girl from Turin who was studying English. He ex- plained that his Hampstead digs shared with three other students, were cramped, so he asked could he bring Sonia to my place to meet quietly. And would I give him my impression? Had he asked me to introduce him to a pleasing, sensible girl with potential, I couldn't have chosen a lovelier girl than this Sonia he'd chosen for himself. Over Christmas 1966, when San- jay had abandoned his Rolls-Royce apprentice course, Rajiv and Sonia took off for Turin for him to meet her family. I did not see them again until they were married, living with Indira, who grew increasingly fond of Sonia. Rajiv con- tentedly worked as pilot for Indian Airlines internal services.

Following Mrs Gandhi's defeat in the 1977 elections and the immediate empowering of the Shah Commission to investigate her misdeeds and those of Sanjay, I spent three months in Delhi. Visiting 12 Willingdon Crescent, a bor- rowed house, almost every day for long hours, I gauged the remarkable fortitude of Rajiv under appalling stress. Of the immediate family, he and Sonia only were free of house arrest and constant police supervision. Despite his extreme concern that their grandmother would be hanged, and the unmerciful taunting of his two children in school, Rajiv never once missed a flying schedule assigned to him. Later, after the death of his brother, and the return in 1980 of his mother as Prime Minister, he remained reluctant to engage in politics. Finally, as the internal conflicts intensified, Rajiv agreed to stand for elec- tion. I have no personal evidence to support the widespread assumption that Rajiv accepted that he would be his mother's heir, this despite the fact that I was in Delhi from 21 March to 6 June 1984, my visit being arranged by Indira. Rajiv, designated Mr Clean, by several Indian editorials, is no politician. Lead- ership has been thrust upon him in the wake of his mother's murder, the murder- ous communal crisis, and now industrial disaster. He has kept his head and demons- trated a decisiveness and ability to cope in the most violent crisis suffered by the Indian people since 1947 when India be- came responsible for itself as an indepen- dent nation.

Rajiv echoes the idea of tolerance as opposed to intolerance. In other words, Secularism, as preached by Gandhi, and demonstrated by his grandfather, Jawahar- lal, and his mother, Indira. In stressing this ancient Indian ideal that goes back to 200 BC when Emperor Ashoka renounced conquest for Buddhist piety, including its political application, Rajiv may possibly touch, in this bedevilled. century, the bat- tered idealism latent in India's voters. But sympathy for him as the son of his gunned- down mother will be insufficient to restort Indian unity unless he has the strength of character to withstand the skilful blandish' ments of politicians and their hangers-on. India is impossible to rule; its people can only be led by a leader whom they have faith in. The spirit of unity, rather than Indira the individual, has been martyred by the terrorism of fundamentalism posing as religion and the bondage. of revived caste interests.

Previous page

Previous page