ii , 9EMESt ,

fiSarcister (t-istiria5

by Ruin! This is what threatened to engulf young Clement Smiles. Ruin, pure and simple.

It had been a proud day, not five years since, when this ardent young champion for truth had his first article accepted by a London editor. Admittedly, that article had appeared in a very obscure corner of an even more obscure London newspaper. But it had been a beginning. And after not many months, he had been writing for The Jupiter itself! Tom Towers, the most fear- less journalist of the age, had befriended Clement Smiles, and it was with the com- mencement of that friendship that the pre- sent tragedy began to unfold.

It is some years now since we met Tom Towers, so I should perhaps remind you that he is now an independent gentleman with a weekly paper of his own, called The Outrage. Whatever evils still lie hidden be- neath the veil of hypocrisy and cant, The Outrage will find out. But, oh, dear reader, I need hardly tell you about The Outrage, for do you not read it yourself? No one will admit to buying The Outrage, and yet Tom Towers sells a mysteriously large number of copies. No one of course reads The Out- rage. And yet most of the drawing-rooms of London are fully acquainted with its contents on the morning of its publication! A mystery here. I fancy, even as we leave our cards in the hall, and make our way up the stairs to these said well-informed drawing-rooms, that copies of The Outrage are being busily stuffed beneath cushions or hidden under chairs. For, respectable opinion believes The Outrage to be unfair and scurrilous. Tom Towers is a man with a mission, a knight in armour fighting the great battle against iniquity in high places. But as he charges into the lists to meet his great opponents, a number of innocent bystanders have not infrequently been im- paled on his lance. If, in his pilgrimage through this dark world Mr Valiant-for- Truth has turned up quite a lot of false- hood, he seems to feel there is nothing much he can do about it.

And it was this same Tom Towers who befriended Clement Smiles and employed him to scrub off the coating of a few whited sepulchres and expose the humbug of a number of scribes and Pharisees. Every week, when The Outrage appeared, the scribes and Pharisees were shivering in their shoes. Here, the shady dealings of a certain gentleman on the Stock Exchange would be exposed to view; and there, the shady residence to which he paid a visit (unbeknown to his wife) on three after- noons a week! Oh, that unfortunate indis- cretion with Lord X's sister! Oh, the folly of signing that accommodation bill! Oh the imbecility which overcame them when they ordered that second bottle of champagne. All and each were subject to the glaring, unforgiving eye of The Outrage and no one was exempt, no one was safe; not admirals, not cabinet ministers, not dukes, not bishops.

Bishops! It was a good many years since Tom Towers last directed his searching gaze towards the bishops. His close friends like ourselves will remember that when he was a young reporter on The Jupiter, he stirred up a lot of trouble in Barchester and managed to force the resignation of poor old Septimus Harding from the War- denship of Hiram's Hospital. All is for- given now, and Mr Harding is a very old man, living in the Deanery with his charm- ing daughter and his son-in-law Mr Arabin. The new bishop (as Mr Harding and his other son-in-law, the Archdeacon, still re- fer to him), the new bishop is still there: rather balder and a little portlier than when we last met him. And of course Mrs Proudie is still there with her new chaplain Mr Slime, the oiliest young gentleman listed in Crockford's clerical directory.

It was young Clement Smiles's misfor- tune that he came into possession (we ask not how) of certain information regarding the Bishop of Barchester. It was informa- tion of a kind which would astonish anyone who respects, as we do, the good name of that Christian gentleman and the wellbeing of the Church of England. This private source, which Clement Smiles was quite unable to reveal to anyone, provided far more discreditable information about Bishop Proudie than could ever be pub- lished in an English newspaper without fear of prosecution. Among these very dis- creditable and unprintable imputations was the preposterous suggestion that his lordship was under the thumb of Mrs Proudie. It was further alleged that the bishop neglected his diocese. It was hinted that he was a Freemason. And it was furth- er suggested that he turned a blind eye nay, that he almost connived in — the mis- demeanours of his inferior clergy. We will bring no blush to the reader's cheek by repeating the foul nature of these misde- meanours. We will merely say that they were perpetrated by those wayward and effeminate gentlemen the Puseyites, who enjoy parading themselves in lace gowns, and brocaded frocks and a great many other fine stuffs which would be the envy of Mrs Proudie herself.

It was impossible, once this information against the poor Bishop had been col- lected, that it could have been withheld from the attention of our friend the editor of The Outrage. And it was equally im-

possible, once Tom Towers had heard of imperfections in that apostolic gentleman that he should not have decided to print all these imputations; to attack the Bishop of Barchester with, as it were, all guns firing.

But the staff of The Outrage had reck- oned without the fury of the Bishop. And even more they had reckoned without the fury of the Bishop of Barchester's wife.

Can we truly imagine, the fearless prose had inquired, that the Bishop would allow these effeminate Puseyites, these nancies and margeries, to parade their lace flum- mery in his diocese if he did not have a sneaking enjoyment of such tomfoolery himself?

The article had been illustrated with a cruel caricature of the bishop dressed in one of his wife's best gowns and bonnets!

With what horror, the very next week, Tom Towers and Clement Smiles had re- ceived a writ! And no ordinary writ, but a writ drawn up (doubtless with the conni- vance of Archdeacon Grantly) by no less person than Sir Abraham Haphazard him- self! Mr Tom Towers, who was used to dealing with lawyers, had attempted to set- tle the matter out of court. But in the en- suing weeks, Sir Abraham had made it per- fectly clear that the Bishop demanded his pound of flesh; indeed, rather more than pound. To be precise, he would not be happy until he had been paid forty thousand pounds!

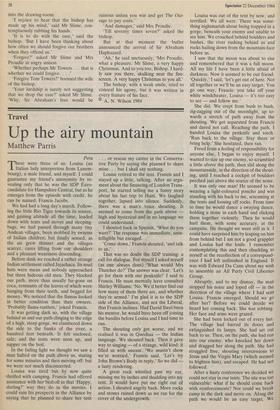

Mr Clement Smiles was uncertain whether he possessed forty pounds, let alone forty thousand. Tom Towers owned a little more, but nothing like that swirl. The whole matter threw the two men into a melancholy frenzy. And on Christmas Eve, which was the coldest, darkest, dankest night of the gloomiest year in their lives the two men sat in Mr Smiles's mean lodgings in Holloway staring sadly at a small boiled fowl which had been placed on the table before them. And this tiny bird was ex' pected to feed Mr and Mrs Smiles, and Mr and Mrs Towers, and their various children who stared at the little bird in the candle' light with ravenous eyes and wondered if they would have anything at all to eat that Christmas.

Through the frosty glass Tom Towers looked out at the cold London sky and for the first time in his adventurous career he felt sickened and crushed.

`Oh,' sniffed his wife into her handker" chief, 'if only this whole sorry busines5 could come to an end!!'

here was no one in the world who

i Twould have said a more hearty AMP to this sentiment than the Bishop of Be chester himself. When he had first read the attacks on his good name in The Outrage' he had taken to his bed in a state of tree" ling and despondency. The tone had been so malicious. And yet what was even more hurtful, so many of the viperish impu?" tions were true! It was true that he lived in a very comfortable place and in a manner, scarcely consistent with the ideals 01 Christian poverty. And yes it was true that he had neglected the more tedious of his diocesan duties. And, ah me, yes, he had used very intemperate language to some of his more vexing clergy — though it asto- nished him how The Outrage came to learn of his slamming a door in the face of the Rector of Puddingdale. And yes, even in this distressing matter of the Puseyites, he had been, well, indulgent.

No one, however, could use the word indulgent to describe the Bishop's wife. And when she had seen the article in The Outrage she had been in no doubt what- soever about the course of action which should be pursued. Letters had been dis- patched at once to Sir Abraham Hapha- zard.

Much to Mrs Proudie's disgust, Sir Abraham had urged caution. While agreeing that every

word of The Outrage Was beneath con- tempt, and the pro- duct of a deranged imagination, Sir Abraham said that `no good ever came' of becoming en- tangled in a libel case. No one read The Outrage. Or if it was read, no one took it seriously. To challen- ge its credentials was, in a fashion, to imply

that its grosser calumnies were worthy of one's notice and they were not worthy of the notice of a Bishop of the Church of England. Sir Abraham had added something about touching pitch.

The bishop was highly gratified that Sir Abraham had been Under the impression that the article in The Outrage was untrue or that the incident of the door-slamming had, in that erudite gentleman's judgment 'all the hallmarks of a calumnious fiction'. Since he remembered the expression of horror on the Rector of Puddingdale's face when the door was slam- med, the bishop took a different view: that the article was exceedingly damaging. He was relieved to learn that the case could go no further.

But his domestic chaplain Mr Slime, and Mrs Proudie, had not let the matter drop and they had insisted that Sir Abraham Concoct a case. The lavish palace and the Country residence and the generally extra- vagant style of life of the bishop were thought, after much clearing of the throat, to be an inappropriate matter to draw to the attention of the public, so the sentences about these remained unchallenged. As for the bishop's occasionally brusque treat- ment of his clergy, that was also best pas- sed over in silence. The neglect of his dio- cese? Tom Towers would have fun with that in court. But ah! What was this? The effeminate flummery of the Puseyites. Could this not be read to imply that the bishop had the most debased tastes? Did it not imply that he nursed within his bosom unmanly predilections which would have disgraced the Emperor Tiberius and which were, in the character of an English bishop by law established quite literally unthink- able? Mrs Proudie thought so. And after several hours of browbeating by that lady, Sir Abraham thought so too. And so the case had proceeded and Mr Smiles and Mr Towers were to be judicially ruined.

The bishop, on this Christmas Eve, had just been attending Evensong in the cathedral and was walking back through the cloisters with the old precentor Mr Harding.

Mr Harding was a good Christian man

sadly at a stra hollea fowl which had been playa on the tthie Wore

and the bishop in his misery felt able to unburden himself to the old clergyman who had seen so many troubles erupt and pass away during the previous half century in Barchester.

'This fellow Towers,' said Harding, not in an angry way, but in the tone you might use to discuss a mild irritant, such as a neighbour's dog.

'But should I be pursuing him?' asked the Bishop. 'Relentlessly. And at Christmas?'

'Lord, how oft shall my brother sin against me and I forgive him — till seven times?' asked Mr Harding.

'I say not unto thee, Until seven times: but, Until seventy times seven,' said the bishop. 'Oh, Harding, what should I do? I have been reading the New Testament.'

`Not always consoling,' said the pre- centor.

'Indeed not,' said the bishop. 'I had for- gotten that St Paul quite specifically for- bids Christian people to indulge in litiga- tion. In his first epistle to the Corinthians. Oh dear, where will it all end?'

'Where such things always end,' said Mr Harding, 'with the lawyers richer and everyone else involved — plaintiff and de- fendant.— more wretched.'

'And yet Mrs Proudie says we might win forty thousand pounds!' said the bishop, momentarily ashamed of the excitement in his voice. 'Of course we would spend the money in charitable ways. . .

'At what a cost you would win such sums!' Mr Harding interrupted. 'At the cost of your reputation as a Christian! And goodness knows what scandal they will concoct in their defence. Do you know, bishop, what you should do — for your own peace of mind, and for the good of the diocese? You should drop this case. This is the season of good will to all men, when we celebrate the coming of forgiveness, the pardon of our enemies. Good night bishop. A happy Christmas to you!'

And the bishop watched the frail old man drift away, more a wraith than a human being, through the shadowy cloisters towards the Deanery.

His words had eat- en into the bishop's heart. Forgiveness. Till seventy times seven. Forty thousand pounds! In an agony of remorse, guilt, anger, greed, he turned back towards the palace, the most miserable man in Barchester. With forty thousand pounds he could endow a school for poor children in the town: the Proudie school! And yet he would have got that money by unchristian revenge.

'Ah, Bishop, at last!' said Mrs Proudie as he entered his own drawing room. 'You seem to have forgotten that we are to en- tertain Sir Abraham Haphazard for Christ- mas dinner. Where have you been? Mr Slime returned from the service a full twen- ty minutes ago. During the second lesson, he came to the conclusion that I should appear in the witness box myself to assert your absolute repugnance for these Puseyite creatures.' 'Could I not express it myself?' asked the bishop. 'Mr Slime is afraid that you will not ex- press your repugnance with sufficient vehe- mence,' said Mrs Proudie, 'and I agree with him.'

'My dear, I have been thinking about the case and I. . .

'I am very glad to hear it. For three months you have given the impression that you have not been thinking about it at all.. It is Mr Slime and I who have done all the work. Isn't that so, Mr Slime?'

And the oily domestic chaplain, grinning from ear to ear, made his repulsive entry into the drawing-room.

'I rejoice to hear that the bishop has made up his mind,' said Mr Slime, con- temptuously rubbing his hands.

'It is to do with the case,' said the bishop. 'But I have been thinking about how often we should forgive our brothers when they offend us.'

'Forgive?' asked Mr Slime and Mrs Proudie in angry unison.

'Whether perhaps Mr Towers. . . that is whether we could forgive. . .

'Forgive Tom Towers?' boomed the wife of the bishop.

'Your lordship is surely not suggesting that we drop the case?' asked Mr Slime. 'Why, Sir Abraham's fees would be

ruinous unless you win and get The Out- rage to pay costs.'

'And damages,' said Mrs Proudie.

'Till seventy times seven?' asked the bishop.

But at that moment the butler announced the arrival of Sir Abraham Haphazard.

'Ah,' he said unctuously, 'Mrs Proudie, what a pleasure. Mr Slime, a very happy Christmas. And to you too, Bishop. I hard- ly saw you there, skulking near the fire- screen. A very happy Christmas to you all.'

The bishop, with a weak smile, tried to conceal his agony, but it was written in every feature of his face. © A. N. Wilson 1984

Previous page

Previous page