The life of language

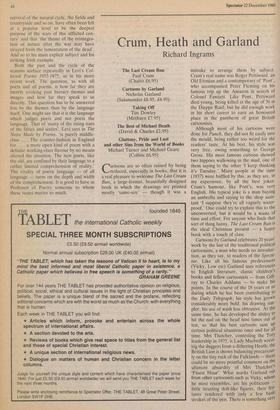

C. H. Sisson The Lamentation of the Dead The Noise Made by Poems Collected Poems 1955-1975 Peter Levi (Anvil Press, £2.95, £6.95/£3.95, £7.95) •

T:an outsider, the procedures for the ppointment of the Professor of Poetry in the University of Oxford are mysterious, and the results can seem eccentric. The appointment is important, because it is one of the few in this country which gives serious recognition to poetry, and it is a pity when it is wasted, as it certainly cannot be said to be in the case of the present holder, who is both poet and scholar. Peter Levi has recently given his inaugural lec- ture and Anvil Press Poetry, who publish it, have at the same time reprinted two of the now Professor's earlier books, The Noise Made by Poems (1977), a volume itself 'based on cannibalised lectures', and the Collected Poems 1955-1975 (1976).

The inaugural lecture, on what might seem the unlikely subject of The Lamenta- tion of the Dead, is published with a translation by Eilis Dillon of 'The Lament for Arthur O'Leary', an 18th-century Irish poem by Eileen O'Connell. Levi apparent- ly read this version of the poem at the close of his lecture, after having 'set it in its true context,. among the greatest examples we have of the lamentation of the dead'. 'It is a disgrace to us all,' as Levi says, 'that so few of us know Irish' — though it is one we share with Yeats and with many disting- uished persons in Ireland, as -well as with the great majority of the undistinguished. Levi may well be right in saying that the poem is 'the greatest . . . written in these islands in the whole eighteenth century', though this is something that those of us who have no ,Irish cannot possibly know, for it is the nature even of the best translations of poetry that they are seen in the end to owe as much or more to the time and language into which the translations are made as to their originals.

This difficulty inevitably haunts Levi's exposition of the 'context' of the poem and makes it as much anthropological as critic- al, for we cannot really lay verse of Shakespeare, which continues to astound us, beside even the best versions of ancient Greek epigrams, Serbo-Croat epic frag- ments, ballads and lays from the Balkans, or the work of O'Leary's widow herself. Levi himself knows all this, for in The Noise Made by Poems we find him recog- nising that the claim he makes for Seferis, that he was 'one of the greatest writers in this century in any language', is 'impossible to substantiate to readers not lucky enough

to know modern Greek'.

The professor had the best of reasons for bringing Shakespeare into his discourse, for 25 October, the date of the inaugural lecture, is also the feast of Crispin and Crispianus, which evokes at once those marvellous lines from Henry V:

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by From this day to the ending of the world But we in it shall be remembered.

It was appropriate not only because of the date but because it is under the shadow or in the blaze — of Shakespeare that all of us whose language is English must speak of poetry, or indeed write it. Levi is intensely conscious — as the present authorities of the Church of England or, for that matter, Rome, are not -- of the presences and absences of the past in our language: 'when you write a poem,' he says, 'you are speaking also to the dead.' He is aware that our language is being 'debauched by a process like the inflation of money',' and that 'that huge unconscious construction which is the life of each language . . . the Logos of each human society is being confused and darkened beyond recogni- tion'.

This thought is clearly behind Levi's choice of a subject for his inaugural lec- ture. When he speaks of Henry V, he passes from the celebration of the heroic dead to the theme of burial and lamenta- tion. He quotes lines from Act IV, Scene 1:

I Richard's body have interred new: And on it have bestowed more contrite tears Than from it issued forced drops of blood.

Who can doubt, anyway, that, in what Levi calls 'the assurance of eternal praise' for those who fought on St Crispin's day, Shakespeare was aware that fame, like chimney-sweepers, must 'come to dust'? Levi goes on to some verses of Eluard which strike me as somewhat too full of big words for all the praise he gives them. The quotation from a poet of our own century, at this point, serves, however, to illustrate the fact that in the end there is not 'modern' poetry but only poetry, subject to the same laws as it has always been, however odd some manifestations may seem to readers who encounter them for the first time.

The argument is, then, behind and be- side the particular subject of the lamenta- tion of the dead, that the debt we owe to ancestral voices cannot remain unpaid without •the failure of our own powers of communication. Levi speaks, in connec- tion with Shakespeare, of 'a ritual that restores the order of nature' and adds that 'odd as it is, one ought to remark that the survival of the natural cycle, the fields and countryside and so on, have often been felt at a popular level to be the deepest purpose of the wars of this afflicted cen- tury' and that 'the theme of the reintegra- tion of nature after the war may have strayed from the lamentation of the dead'. And so to his main explicit subject and his striking Irish example.

Both the past and the cycle of the seasons surface repeatedly in Levi's Col- lected Poems 1955-1975, as in his more recent work. The question, as with all poets and all poems, is how far they are merely evoking past literary- themes and images and how far they speak to us directly. This question has to be answered less by the themes than by the language itself. One might say that it is the language which judges poets and not poets the language. That of 'many of the rising stars of the fifties and sixties', Levi says in The Noise Made by Poems, 'is purely middle- class . . . The counter-fashion in England for . . . a more open kind of poem with a definite working-class flavour by no means altered the situation. The new poets, like the old, are confined by their language to a rather limited comprehension of reality.' The vitality of poetic language — of all language — turns on the depth and width of the comprehension. It is good to have as Professor of Poetry someone to whom these issues matter so much.

Previous page

Previous page