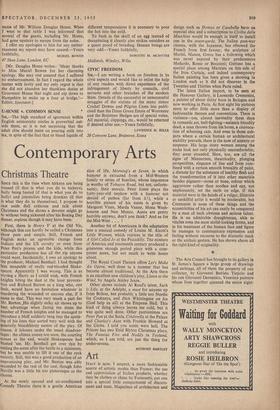

Art

ITALY is now, I suspect, a more fashionable source of artistic modes than France; the use and appreciation of Italian products, whether they be clothes or china by Fornasetti, put one into a special little compartment of discern- ment and taste. Magazines of architecture and

design such as Domus or Casabella have an especial chic and a subscription to Civilta delle Macchine would be enough in itself to install one in the avant-garde. The Italian post-war cinema, with the Japanese, has elbowed the French from first favour; the sculpture of Marini, Manzu, Greco has a following which was never enjoyed by their predecessors Medardo, Rosso or Boccioni; Guttuso has a special place among Marxists on this side of the Iron Curtain, and indeed contemporary Italian painting has been given a showing in London such as it did not discover in the Twenties and Thirties when Paris ruled.

The latest Italian import, to be seen at the Hanover Gallery, is Leonardo Cremonini, a painter of about thirty born in Bologna and now working in Paris. At first sight his pictures seem to offer little more than a display of fashionable themes and conventions. There is violence—yes, almost inevitably these days in romantic art, bull-fighting—animals bloodily dead, a man thrown from his horse, a convoca- tion of scheming cats. And even in those sub- jects where a certain human or architectural stability prevails, there is the note of anxiety or suspense. His large stony women among the rocks look not only physically uncomfortable; they seem stranded. Here, too, are all the signs of Mannerism, theatricality, plunging perspectives, elegance of line and form com- bined with a certain smooth brutality of paint, a distaste for the substance of healthy flesh and the transformation of it into other materials besides pigment—stone or bone, colour which aggravates rather than soothes and can, not unpleasantly, set the teeth on edge. If this material were in the hands of a vulgar, illiterate or unskilful artist it would be intolerable, but Cremonini is none of these things and the eccentricities of his art can easily be conquered by a man of such obvious and serious talent. He is an admirable draughtsman, able to vitalise even the most stolid-looking forms, and in his treatment of the human face and figure he manages to communicate expression and feeling without recourse to the dramatic mask or the archaic gesture. He has shown above all the right kind of originality.

The Arts Council has brought to its gallery in St. James's Square a large group of drawings and etchings, all of them the property of one collector, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and his son Giovanni Domenico, Venetian painters whose lives together spanned the entire eight- eenth century. We are confronted hero by the essential conventionalism of draughtsmanship, by a superb system of graphic notation. Here is proof that the most important qualities in drawing are knowledge, intelligence and skill, without which feeling, intuition, sympathy, a will to create, remain dumb. These men, the father in particular, had a huge stock of visual recollections and—more important perhaps— an extraordinary sense of articulation, of the way things work, how bodies are joined together in any circumstance or upon any occasion. Their extraordinary inventiveness, which encouraged them to feats of virtuosity, could always be handled and expressed in graphic terms. Giovanni Battista's Holy Family (No. 3 in the exhibition) is a splendid example of their gifts. Every line, accent and wash has a precise, indicative meaning. This is absolutely what Picasso meant by 'My object is to show what I have found and not what I am looking for.' This confident and coherent demonstration of fact in terms of an absolutely controlled and rational language of signs indeed made possible the vast professional career of these artists, their output of frescoes from Stockholm to Madrid. It is hard not to believe that Romantic prejudices against such accomplishment in favour of naivety and so-called sincerity do not ultimately threaten to dry up, inhibit, many an artist's production. Those of our younger painters who aspire to paint monumentally on walls, to make public statements in public places, might well look at Tiepolo rather than Courbet.

Previous page

Previous page