THE INFLATION BOGEY

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

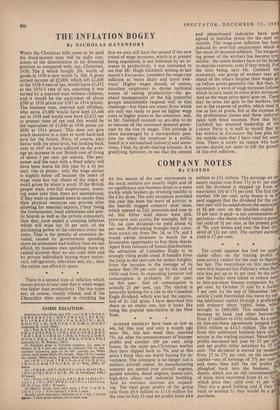

WHEN the Christmas bills come to be paid the fixed-income man will be sadly con- scious of the deterioration in his financial position as compared with, say, Christmas, 1938. The £ which bought 20s. worth of goods in 1938 is now worth 7s. 10d. A gross earned income of £2,000, which left £1,608 at the 1938-9 rate of tax, would leave £1,472 at the 1954-5 rate of tax, assuming it was earned by a married man without children, and it would be the equivalent of about £580 at 1938 prices (or £387 at 1914 prices). The business man, married and childless, who earns £5,000 would have kept £3,446 net in 1938 and would now have £2,612 net at present rates of tax and this would be the equivalent of £1,040 at 1938 prices (or £686 at 1914 prices). This does not give much incentive to a man to work hard and save for the future. Wars, of course, play havoc with the price level, but looking back only to 1947 we have suffered on the aver- age an increase in our British cost of living of about 5 per cent. per annum. The pen- sioner and the man with a fixed salary will have been worse hit this year by a 61 per cent. rise in prices: only the wage earner is slightly better off because the index of wage rates has run ahead of the index of retail prices by about a point. If the British people want over-full employment, mean- ing more jobs than there are unemployed, if they want to demand more in money than their physical resources can provide after allowing for essential exports, (`they' being the Government, local authorities and pub- lic boards as well as the private consumer), then they must expect a creeping inflation which will wipe out 50 per cent. of the purchasing power of the currency every ten years. That is the penalty of excessive de- mand, caused by governments spending more on armament and welfare than we can afford, by business men spending more on capital account than we can cope with and by private individuals buying more motor- cars, refrigerators, television sets, etc., than the nation can afford to spare.

There is a second type of inflation which causes prices to soar and that is when wages rise faster than productivity. The two types are, of course, closely related, and if the Chancellor does succeed in checking the

first we may still have the second if the new round of wage increases, which is at present being negotiated, is not followed by an in- crease in productivity. I was interested to see that Mr. Hugh Gaitskell, writing in last month's Encounter, considers the wage-cost inflation as 'more likely and more awk- ward.' Higher wages should, of course, stimulate employers to devise technical means of raising productivity—the go- ahead managements of the big industrial groups undoubtedly respond well to that challenge—but there are many firms which are only too ready to pass on higher wage costs in higher prices to the consumer, and, as Mr. Gaitskell reminds us, are able to do so because of the increased demand gener- ated by the rise in wages. This attitude is often encouraged by a monopolistic posi- tion (as when the employer is a public board in a nationalised industry) and some- times, I fear, by profit-sharing schemes. It is gratifying, however, to see that the cement and plasterboard industries have noW agreed to stabilise prices for the next si% months. The wage-cost inflation has been induced by over-full employment which is the result of demand-inflation. The bargain- ing power of the workers has become irre-, sistible : the union leaders have so far failed to exercise restraint, even if they would. For the time being, says Mr. Gaitskell the economist, one group of workers may get ahead of the others because their wages go up before prices generally rise. But then, in succession, a wave of wage increases follows which in turn leads to more price increases. And so the wage-price spiral goes on. There may be some net gain to the workers, but not at the expense of profits, which tend to rise as fast as prices, but at the expense of the professional classes and those unfortu• nates with fixed incomes. Now that Mr Gaitskell has assumed leadership of the Labour Party it is well to record that he has written in Encounter the best plea for the middle class that I have read for some time. There is surely no reason why both parties should not unite to kill the growth of this evil inflation.

Previous page

Previous page