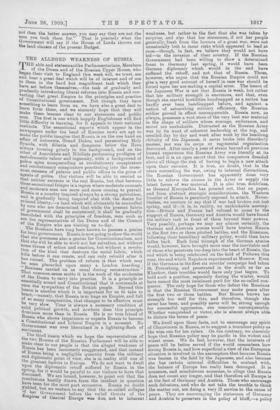

THE ALLEGED WEAKNESS OF RUSSIA. T HE able and statesmanlike Parliamentarians,

Members of the Duma and of the Russian Upper House, who began their visit to England this week will, we trust, see and hear a great deal which will be of interest and of use to them in the hard but magnificent task which they have set before themselves,—the task of gradually and prudently introducing liberal reforms into Russia and con- verting that great Empire to the principles and practice of Constitutional government. But though they have something to learn from us, we have also a great deal to learn from them, and we sincerely hope that they will make these lessons clear to our statesmen and public men. The first is one which happily Englishmen will find little difficulty in learning, for it appeals to their national instincts. The sensational reports which appear in the newspapers under the head of Russian news are apt to make the public imagine that Russia is on the one hand an affair of autocrats, Grand Dukes, and persecuting Holy Synods, with Siberia and dungeons below the Neva always looming grimly in the background, and on the other of Anarchists and Nihilists performing prodigies of melodramatic valour and ingenuity, with a background of police spies masquerading as revolutionary conspirators and revolutionary conspirators penetrating into the inner- most recesses of palaces and public offices in the guise of agents of police. Our visitors will be able to remind us that neither extreme is the real Russia, but that between these sensational fringes is a region where moderate counsels and moderate men are more and more coining to prevail. Russia is a country inspired always by a strong patriotism, and is gradually being inspired also with the desire for ordered liberty,—a land which will ultimately be controlled by, men who are determined that while the present fabric 9i government shall be maintained, it shall be gradually inoculated with the principles of freedom, men such as are the representatives of the Duma and of the Council of The Empire who are visiting us to-day. Ihe Russians have long been known to possess a genius for local government. Russia is now going to show the world that she possesses also a genius for Constitutionalism, and that she will be able to work out heir salvation, not without some ine throes of action and reaction, but without a revolu- tion of the kind that destroys the social fabric, which kills before it can create, and can only rebuild after it has ruined. Till3 problem of reform is that which may :13.e. seen placarded upon many a London hoarding Business carried on as usual during reconstruction." That common-sense motto it is the work of the moderates of the Duma to carry into practice. It is a principle so essentially sound and Constitutional that it commands at once the sympathies of the British people. Beyond this lesson is another which it is important for us to take to heart,—namely, that Russia is so huge an Empire, and full be so many complexities, that changes to be effective must De very slow. Time is always a necessary condition of solid political growth, and nowhere does this principle dominate more than in Russia. lie is no true friend of Russia who shows impatience or expects Russia to become a Constitutional Had Liberal Empire in a moment. No Government was ever liberalised in a lightning-flash of sentiment.

The third lesson which we hope the representatives of the two Houses of the Russian Parliament will be able to make clear to our people is that the alleged weakness of Russia has been immensely exaggerated, and that instead. of Russia being a negligible quantity from the military and diplomatic point of view, she is in reality still one of the greatest factors in Europe. We do not want to dwell upon the diplomatic rebuff suffered by Russia in the spring, for it would be painful to our visitors to have that discussed. We are bound, however, to point out that the conclusions hastily drawn from the incident in question . have been for the most part erroneous. Russia no, doubt yielded, but we venture to say that the so-called collapse If her Government before the veiled throats of the 21°I)Iree of Central Europe was due, not to inherent weakness, but rather to the fact that she was taken by surprise, and also that her statesmen, if not her people generally, fresh from the horrors of a great war, were not unnaturally loth to incur risks which appeared to lead at once—though, in fact, we believe they would not have led—to the invasion of their country. If the Russian Government had been willing to show a determined front to Germany last spring, it would have been German diplomacy which would in the end have suffered the rebuff, and not that of Russia. Those, however, who argue that the Russian Empire could not give a very good account of herself in case war should be forced upon her are making a capital error. The lesson of the Japanese War -is not that Russia is weak, but rather that her military strength is enormous, and that, even though she started hostilities handicapped as a nation has hardly ever been handicapped before, and against a nation of astonishing military efficiency, the Russian soldier proved. in effect unconquerable. Russia now, as always, possesses a vast store of the very best war material in the shape of soldiers whose courage, endurance, and moral are unshakable. Distracted as the Russian Army was by its want of coherent leadership at the top, and assailed day by day and week after week by the headlong chivalry of the Japanese, it never broke into disorderly masses, nor was its corps or regimental organisation destroyed. After nearly a year of strain beyond all previous buinau experience the Russian Army was literally at its best, and it is an open secret that the conquerors dreaded above all things the risk of having to begin a new attack upon their enemies. It is true, no doubt, that in the years succeeding the war, owing to internal distractions, the Russian Government has apparently done very little to reform the abuses in the Army or supply the latest forms of war material. It is also true, doubtless, as General Kuropatkin has pointed out, that on paper, mad from abstract strategic considerations, the Western frontier of Russia is peculiarly exposed to attack. Never- theless, we venture to say that if war had broken out last spring, and if—it is, in reality, an unthinkable assump- tion—Britain and France had refused to come to the support of Russia, Germany and Austria would have found the military task in front of them beyond their powers. Very possibly, perhaps wo may say almost certainly, the German and Austrian armies would have beaten Russia in the first two or three pitched battles, and the Russians, following their hereditary military policy, would then have fallen back. Each fatal triumph of the German armies would, however, have brought more near the inevitable end of those who penetrate too deep into the heart of Russia, the end which is being celebrated on the field of Pultowa this year, the end which Napoleon experienced at Moscow. Even if the Germans in the first six months' campaign had taken St. Petersburg, and penetrated in the south as far as Kharkov, their troubles would have only just begun. To hold such a position, especially during the winter, would have meant the most imminent peril for the so-called con- queror. The only hope for those who defeat the Russians is that the Russian Government may make peace after the first two or three battles. But Russia knows her strength too well for this, and therefore, though she never has been, and possibly never will be, strong enough for successful aggression, she remains unconquerable.

Whether vanquished or victor, she is almost always able to dictate the terms of peace.

We dwell upon these facts, not to encourage any spirit of Chauvinism in Russia, or to suggest a truculent policy as the wise one for her rulers. On the contrary, -we sincerely hope that Russian policy may be pacific in the widest and wisest sense. We do feel, however, that the interests of peace will be better served if the world remembers how strong Russia is, and how superficial a view of the European situation is involved in the assumption that because Russia was beaten in the field by the Japanese, and also because she has certain internal difficulties to contend with the balance of Europe has really been deranged. It is nonsense, and mischievous nonsense, to allege that Russia does not count any longer, and that therefore all Europe is at the feet of Germany and Austria. Those who encourage such delusions, and who do not take the trouble to think the matter out, are doing a very ill service to the cause of peace. They are encouraging the statesmen of Germany and Austria to persevere in the policy of bluff,—a policy which if persisted in is almost certain to lead to war. We must not forget that the question of the Southern Slays is still with us, and may at any moment again become acute. If it does, we venture to say that it will not be safe to suppose that Russia can be again humiliated. Those who act on the assumption that Russia is too weak to be worth considering will before long find out their mistake.

Previous page

Previous page