Motoring

Thunderbirds are go

Alan Judd

Icouldn't have attended the press day at London's motor show with all the other motoring correspondents even if I had been invited because I was enjoying Andrew Lycett's biography of Ian Fleming (see review). Lycett doesn't go into great detail on Fleming's cars probably because he assumes that books and marriages and so on were more important, but I'm not so sure. I suspect that at various periods of Fleming's life cars ranked almost with golf; there's probably another book there.

One of Fleming's more touching aspects was his abiding interest in how things work. He enjoyed talking to the people who made and maintained them more than to his wife's smarter and cleverer friends. On the great train from Chicago to Los Angeles his companion arranged for him to ride in the cab: 'He was all over the engine, went back into the infernal noise of the diesel room — alone — and interrogat- ed the engineer and his assistant on every- thing from the block signalling system to the "dead man's control". . . He got off every stop in New Mexico and Arizona, talking to the men serving the train, walk- ing briskly round the desert architecture stations. . .

Not all Fleming's cars were glamorous but when it came to the big beasts he knew what he was about and, in putting the early Bond into an open-topped super-charged Bentley, he wrote from experience. He first topped 100 mph in 1928 in a three-litre Bugatti, just outside Henley. His own car at the time was a Standard Tourer but he compensated by driving too fast. On a level crossing in Austria he failed to beat the train and was dragged fifty yards, emerging from the wreckage shaken, not stirred. His first overseas assignment for Reuters was to cover the Alpine motor trials, during which he navigated for Donald Healey in a record-breaking 4.5 Invicta.

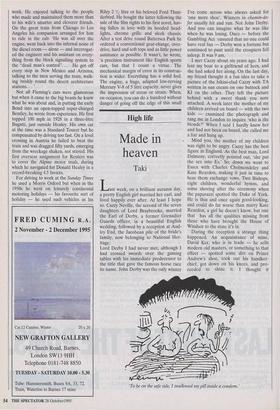

For driving to work at the Sunday Times he used a Morris Oxford but when in the 1950s he went on leisurely continental motoring holidays — his favourite sort of holiday — he used such vehicles as his Riley 2 1/2 litre or his beloved Ford Thun- derbird. He bought the latter following the sale of the film rights to his first novel, hav- ing fallen in love with its hooded head- lights, chrome grille and sleek chassis. After a test drive round Battersea Park he ordered a conventional gear-change, over- drive, hard and soft tops and as little power assistance as possible. It wasn't, he wrote, `a precision instrument like English sports cars, but that I count a virtue. The mechanical margin of error in its construc- tion is wider. Everything has a solid feel. The engine, a huge, adapted low-revving Mercury V-8 of 5 litre capacity, never gives the impression of stress or strain. When, on occasion, you can do a hundred without danger of going off the edge of this small

Previous page

Previous page