TRAVEL

Kilimanjaro

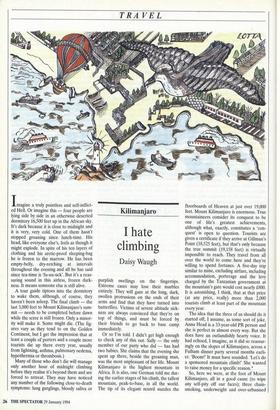

I hate climbing

Daisy Waugh

A tour guide tiptoes into the dormitory to wake them, although, of course, they haven't been asleep. The final climb — the last 3,000 feet to Mount Kilimanjaro's sum- mit — needs to be completed before dawn while the scree is still frozen. Only a minor- ity will make it. Some might die. (The fig- ures vary as they tend to on the Golden Continent, but I get the impression that at least a couple of porters and a couple more tourists die up there every year, usually from lightning, asthma, pulmonary oedema, hypothermia or thrombosis.) Many of those who don't die will manage only another hour of midnight climbing before they realise it's beyond them and are forced to retreat. They may have noticed any. number of the following close-to-death symptoms: lung gurglings, bloody saliva or purplish swellings on the fingertips. Extreme cases may lose their marbles entirely. They will gaze at the long, dark, swollen protrusions on the ends of their arms and find that they have turned into butterflies. Victims of severe altitude sick- ness are always convinced that they're on top of things, and must be forced by their friends to go back to base camp immediately.

Or so I'm told. I didn't get high enough to check any of this out. Sally — the only member of our party who did — has had two babies. She claims that the evening she spent up there, beside the groaning man, was the most unpleasant of her life. Mount Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain in Africa. It is also, one German told me dur- ing the earlier stages of his climb, the tallest mountain, peak-to-base, in all the world. The tip of its elegant nostril nuzzles the floorboards of Heaven at just over 19,000 feet. Mount Kilimanjaro is enormous. True mountaineers consider its conquest to be one of life's greatest achievements, although what, exactly, constitutes a 'con- quest' is open to question. Tourists are given a certificate if they arrive at Gillman's Point (18,525 feet), but that's only because the true summit (19,158 feet) is virtually impossible to reach. They travel from all over the world to come here and they're willing to spend fortunes. A five-day trip similar to mine, excluding airfare, including accommodation, porterage and the levy charged by the Tanzanian government at the mountain's gate would cost nearly £800. It is astonishing, I think, that at that price (at any price, really) more than 2,000 tourists climb at least part of the mountain every year.

The idea that the three of us should do it started off, I assume, as some sort of joke. Anna Head is a 33-year-old PR person and she is perfect in almost every way. But she does have an outlandishly hearty voice. It had echoed, I imagine, as it did so reassur- ingly on the slopes of Kilimanjaro, across a Fulham dinner party several months earli- er. `Boom!' It must have sounded. `Let's do a sponsored mountain climb!' She wanted to raise money for a specific reason.* So, here we were, at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, all in a good cause (to wipe any self-pity off our faces); three chain- smoking, underweight and over-urbanised

TRAVEL

girlies, raising a bit of a titter by giving it a bit of a go, ho ho. Nothing to be ashamed of in that. Anna had had the foresight to ensure that sponsorship money was raised from the moment we arrived in Tanzania. It meant we could turn back at any point.

I hate climbing. I have asthma. I've smoked ever since I was 13. The thing had all been planned so far in advance that I don't think any of us really believed it would happen. I joined a gym and in two months made five visits there (four of them in the week before departure). I gave up smoking for six days. I remembered, conve- niently, that I'd had bronchitis as a child. Anna said 'Boom! I mean, how bad is your asthma?' and I clutched my ears and quiv- ered. It was the feeblest line of the feeblest resistance only, and here I was at the base of this wretched, terrifying mountain.

The route we were taking is by far the mountain's most popular. Africa bores have been known to call it 'the motorway', and it's true — the path is strewn with signposts and toilet facilities and Germans. I suppose on that first day we must have bumped into at least 50 people — long-jawed, hefty types pounding their way back to base. They all, without exception, claimed to have reached one or other of the summits. But I worked out that of all the people we got to know on our way up the mountain only 30 per cent even reached Gillman's Point. Which leads one to question whether some of them weren't telling us lies.

We spent our first night on the mountain at just below 9,000 feet. The walk to that point was supposed to have taken only three hours. We took it slowly — six hours. Still, we arrived at the camp far too early for comfort. By seven o'clock that evening we had already examined its nice clean lays and our nice clean electrically lit log cabins. We had made friends with a couple of English boys, eaten a three-course supper cooked for us by our porters and learned the rules to a new game of cards. We had examined the view (it was spectacular), wondered at the spread of a bushfire over in Kenya, which illuminated at least a quar- ter of the horizon, and there was nothing much left to do but go to bed.

One night down, officially three to go. We were depressed by our fellow climbers. Most were middle-aged Swiss and German persons of indeterminate sex. They sported their ugly clothes and their shapeless bot- toms without any apparent sense of shame, and most of them remembered to supple- ment their diets with plastic measuring- scoopfuls of glucose. We were awoken that night by the growl of a passing leopard, which was a high point. But then the morning came and it was time to start walking again. We were all so depressed by the thought of the day ahead that none of us spoke until lunch- time. At tea-time we argued about what we should do with the rest of our time in Tan zania if we decided to turn back tonight. I wanted to go to Zanzibar, but Anna, who is probably above averagely honourable, thought it would be inappropriate to reward failure with a treat. The air was very thin by then, so our argument lacked lustre. That evening the view of the plain was obscured by the top of the clouds. Sally's hands had erupted and turned blue but she insisted she was all right. Anna couldn't eat and had a violent headache and I was depressed and couldn't breathe. We were all extremely cold.

In the morning Anna and I turned back. The three of us had spent that night attempting to sleep in another tent-shaped wooden hut, this time at 12,500 feet. I apparently was the only one who succeed- ed. They claimed that my nose and lung and general snorting areas had been mak- ing such disgusting gurgling noises that the two of them had lain awake, cursing me, all night.

They asked me if I was OK to continue, what with my blue-tinged face and violent snorting. And I wondered. And I looked up to the final third of the mountain, imagined the sick-spangled route that led to the mountain's crater and thought of what lay ahead and of my asthma and my dirty hair and of the unknown country splayed and waiting to be discovered at my aching feet, and I thought of two more days of this repetitive, boring nightmare. And I knew that from now on it would get much worse. And I thought what it came down to, any- way, was the utterly reasonable but slightly embarrassing conclusion that, no, I wasn't OK. I'd seen the mountain now. Time to head for something different. Like Zanzibar.

But we never made it.

*Donations to The Trevor Jones Tetraplegic Trust can be sent to: 46 Hay's Mews, London W1X 7RT; tel: 071-495 7099. The Kiliman- jaro Challenge was sponsored by British Air- ways, Abercrombie & Kent, Damart, Thomas Cook and Flames Gym, Galena Road, Lon- don W6; tel 081-741 8536.

'She bit off more than she could chew.'

Previous page

Previous page