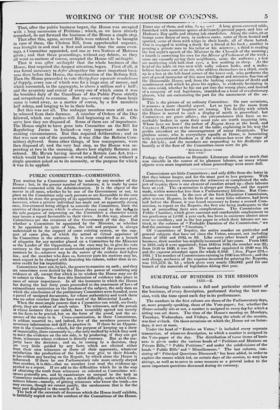

PUBLIC COMMITTEES—COMMISSIONS.

THE motion for a Committee may be made by any member of the House; but, in the greater number of instances, it is made by some member connected with the Administration. It is the object of the mover in all cases, whether he be one of the Government or not, to place on the Committee only such persons as are favourable to the case on which he rests the propriety of its appointment. For the most part, however, when a private individual has made out an apparently strong case, Government being obliged to concede the Committee, limit the exercise of their power, which is utmost always equal to the tasirasi.to the sole purpose of impressing on the Committee a character which may insure a report favourable to their views. In this way, almost all Committees are the creatures of the Government of the day. But whether a Committee be appointed by the Minister, or whether it be appointed in spite of him, the end and purpose is always understood to be the support of some existing system, or the sup- port of some plan, of which the actual or virtual appointer of the Committee is the advocate. It is even considered as a breach of etiquette for any member placed on a Committee by the Minister or the Leader of the Opposition, as the case may be, to give his vote contrary to the expressed or understood opinions of the person whose nominee he is—whatever may be the nature of the evidence laid before him; and the member who does so, however pure his motives may be, must expect to be charged with deserting his colours, rather than to re- ceive credit for his impartiality. Committees have not, bylaw, the power to examine on oath ; and they are sometimes even denied by the House the power of examining any evidence at all, except that which in its wisdom the House may see fit to submit to them. Nor does this limitation of evidence take place in cases of minor importance. In all the instances in which the House has during the last forty years proceeded to the enactment of laws of extraordinary restriction on the freedom of the subject, the only data on which the conclusions of the preliminary Committee were founded, were a parcel of unsigned documents, for whose authenticity and tiuth there was no other voucher than the bare word of the Ministerial Leader.

When the most ample powers that a Committee can wield, are freely given, they are seldom of much value. The witnesses, and the person at whose instance they are called, have invariably agreed not merely on the facts to be proved, but on the form of the proof, and the se- quence of the steps in it. Cross-examination, in these Committees, is seldom resorted to ; and indeed, few of the members possess the necessary information and skill to practise it. If there be an Opposi- tion in the Committee,—which, for the purpose of keeping up a show of impartiality, there commonly is,—the only method by which they seek to meet the evidence on the one side, is by producing, if they can get them, witnesses whose evidence is directly contrary. But as the ma- jority have the decision; and as, in coming to a decision, they are very little guided by any facts which are elicited either from their own witnesses or those of their opponents, whatever satisfaction the production of the latter may give to their friends, it has seldom any bearing on the Report, by which alone the House is influenced. If there be one Parliamentary rule more strictly obeyed than another, it is this—that no member ever read the evidence ap- pended to a report. If we add to the difficulties which lie in the way of obtaining the truth from witnesses so selected as Committee wit- nesses generally are, and by examinators so unequal to the task as Committee members generally are, a third difficulty, under which Com- mittees labour—namely, of getting witnesses who know the truth—we May excuse, though we cannot justify, the carelessness that is for the most part displayed in the search of it.

The lack of the externals of decorum which the House itself exhibits, is faithfully copied out in the conduct of the Committees of the House.

Enter one of them, and what do ne see? A long green-covered table, furnished with numerous quires of delicately-pressed paper, and lots of Hudson's Bay quills and shining ink-standishes. Along the sides, sit or lounge some dozen of men, in undress coats, some of them booted and spurred, some of them with whips in their hands, all of them batted. One is engaged in writing a frank for a friend at his back ; another is penning a private note to his tailor or his mistress ; a third is reading the last night's speech of the Minister in the Chronicle of the morning; a fourth is correcting his own for the Mirror ofParliament of the week; some are vacantly eyeing their neighbours, some the audience ; a few are meditating with half-shut eyes, a few nodding to sleep. At the head of the table sit two men with sadly solemn looks, and a make- believe business sort of an air, who address themselves to a third, stuck up in a box at the left-hand corner of the lower end, who performs the part of grand instructor of this most intelligent and attentive fraction of the Honourable House, and, from the lurking expression of doubt and wonderment with which he gives his replies, is evidently hesitating irt his own mind, whether he has not got into the wrong place, and instead of a company of real legislators, stumbled on a knot of revolutionary players, who are caricaturing the part for the amusement of the au- dience.

This is the picture of an ordinary Committee. On rare occasions, it assumes a more cheerful aspect. Let us turn to the room from which those bursts of laughter are issuing. The facility with which the House is moved to such a display of mirth is proverbial : but Committees are grave affairs ; the circumstances that have so re- markably broken in upon their usual rule are worth inquiring into. Whom have we here? the author of Eugene Arum at the head, and CHARLES MATHEWS at the foot of the table, explaining in his way the profits attendant on the encouragement of minor theatricals. The glorious mime, who is everywhere equally at Home, is luxuriating with as unrestrained freedom as if the witness-box were the stage of the Adelphi ; and the members are responding to his drolleries as heartily as if the floor of the Committee-room were its pit.

" Ridentem dicere erum Quis vetat."

Perhaps the Committee on Dramatic Literature elicited as much that was valuable in the course of its pleasant labours, as many whose objects were more important and whose proceedings were more dull.

Previous page

Previous page