Will Jim fix it?

George Gale

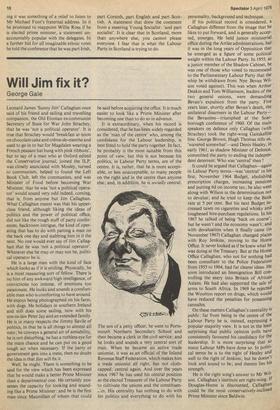

Leonard James 'Sunny Jim' Callaghan once said of his friend and sailing and travelling companion, the Old Etonian ex-communist Secretary of State for War John Strachey, that he was 'not a political operator'. It is true that Strachey would 'breakfast at noon on chocolate cake and creme-de-menthe and used to go in to bat for Magdalen wearing a French peasant hat hung with pink ribbons', but to say of a man who at Oxford edited the Conservative journal, joined the ILP, was closely associated with Mosley, turned to communism, helped to found the Left Book Club, left the communists, and was Minister of Food before becoming War Minister, that he was 'not a political opera- tor' would sound very odd indeed, coming, that is, from anyone but Jim Callaghan. What Callaghan meant was that his upper- class friend, although liking the ideas of politics and the power of political office, did not like the rough stuff of party confer- ences, backroom intrigue, the kind of oper- ating that has to do with patting a man on the back one day and stabbing him in it the next. No one would ever say of Jim Callag- han that he was 'not a political operator'. Whatever else he may or may not be, politi- cal operator he is.

He is a large man with the kind of face which looks as if it is smiling. Physically, he is a most reassuring sort of fellow. There is no hint of any awkward high intelligence, of convictions too intense, of emotions too passionate. He looks and sounds a comfort- able man who is comforting to have around. He enjoys being photographed on his farm, with dogs. He holidays in southern Ireland and still does some sailing, now with his son-in-law Peter Jay and an extended family. He is in many respects the Jimmy Savile of politics, in that he is all things to almost all men; he conveys a general air of amiability, he is not disturbing, he has a ruthless eye for the main chance and he can put on a good tough act when necessary. If the party or government gets into a mess, then no doubt the idea is that Jim will fix it.

Well, he might. There is something to be said for the view which has been expressed that he would make a better Prime Minister than a departmental one. He certainly pos- sesses the capacity for looking and sound- ing like a Prime Minister : and he is the first man since Macmillan of whom that could be said before acquiring the office. It is much easier to look like a Prime Minister after becoming one than to do so in advance.

It is extraordinary, when his record is considered, that he has been widely regarded as the 'man of the centre' who, among the candidates for the Labour leadership, is best fitted to hold the party together. In fact, he probably is the most suitable from this point of view, but this is not because his politics, in Labour Party terms, are of the centre. It is, rather, that he is more accept- able, or less unacceptable, to many people on the right and in the centre than anyone else; and, in addition, he is socially central.

The son of a petty officer, he went to Ports- mouth Northern Secondary School and then became a clerk in the civil service; and he looks and sounds a very central sort of man. When he became an active trade unionist, it was as an official of the Inland Revenue Staff Federation, which makes him a trade unionist all right, but not cloth- capped : central again. And over the years since 1967 he has used his central position as the elected Treasurer of the Labour Party to cultivate the unions and the constituen- -es. His centrality has nothing to do with his politics and everything to do with his personality, background and technique.

If his political record is considered, a Callaghan different from the image that he likes to put forward, and is generally accep- ted, emerges. He held junior ministerial office during the Attlee administrations, but it was in the long years of Opposition that he emerged as a figure of some political weight within the Labour Party. In 1955, as a junior member of the Shadow Cabinet, he was one of those who voted to recommend to the Parliamentary Labour Party that the whip be withdrawn from Nye Bevan Wil- son voted against). This was when Arthur Deakin and Tom Williamson, leaders of the two general unions, were demanding Bevan's expulsion from the party. Five years later, shortly after Bevan's death, the unilateral disarmers in the Labour Party— the Bevanites—triumphed at the Scar- borough conference of 1960. Of the main speakers on defence only Callaghan (with Strachey) took the right-wing Gaitskellite line. George Brown, Hugh Thomas tells us, 'wavered somewhat'—and Denis Healey, in early 1961, as shadow Minister of Defence, committed the party to ending the indepen- dent deterrent. Who was 'central' then?

It could be argued that Callaghan—again in Labour Party terms—was 'central' in his first, November 1964 Budget, abolishing prescription charges, increasing pensions and putting 6d on income tax; he also went along with Wilson in the determination not to devalue; and he tried to keep the Bank rate at 5 per cent. But his next Budget in- creased taxes on cigarettes and whisky and toughened hire-purchase regulations. In his 1967 he talked of being 'back on course'; but he wasn't and the economy wasn't; and with devaluation when it finally came (in November 1967) Callaghan changed places with Roy Jenkins, moving to the Home Office. It never looked as if he knew what he was doing at the Treasury. But at the Home Office Callaghan, who not for nothing had been consultant to the Police Federation from 1955 to 1964, had far clearer ideas. He soon introduced an Immigration Bill con- trolling the entry into Britain of African Asians. He had also supported the sale of arms to South Africa. In 1969 he rejected the Wootton report on drugs, which would have reduced the penalties for possessing cannabis.

On these matters Callaghan's centrality is public: far from being in the centre of the Labour Party he is, instead, expressing a popular majority view. It is not in the least surprising that public opinion polls have consistently favoured his candidacy for the leadership. It is more surprising that so many Labour MPs have done so. In politi- cal terms he is to the right of Healey and well to the right of Jenkins; but he doesn't look and sound to be; and therein lies his strength. He is the right wing's answer to Mr Wil- son. Callaghan's instincts are right-wing. If Douglas-Home is discounted, Callaghan could be the most conservatively-inclined Prime Minister since Baldwin.

Previous page

Previous page