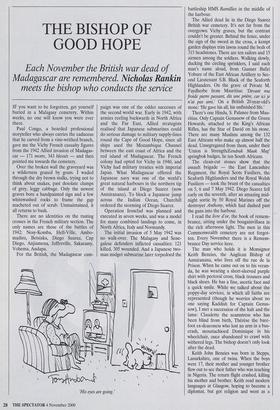

THE BISHOP OF GOOD HOPE

Each November the British war dead of

Madagascar are remembered. Nicholas Rankin

meets the bishop who conducts the service

IF you want to be forgotten, get yourself buried in a Malagasy cemetery. Within weeks, no one will know you were ever there.

Paul Congo, a bearded professional storyteller who always carries the caduceus that he carved from a vine-writhed branch, gave me the Vichy French casualty figures from the 1942 Allied invasion of Madagas- car — 171 morts, 343 blesses — and then pointed me towards the cemetery.

Over the broken wall the graveyard was a wilderness grazed by goats. I waded through the dry brown stalks, trying not to think about snakes, past desolate clumps of grey, leggy cabbage. Only the newest graves bore a handpainted sign and a few whitewashed rocks to frame the gap macheted out of scrub. Unmaintained, it all returns to bush.

There are no identities on the rusting crosses in the French military section. The only names are those of the battles of 1942: Nosy-Komba, Hell-Ville, Ambo- madiro, Betsiaka, Diego Suarez, Cap Diego, Anjiamena, Joffreville, Sakaramy, Vohema, Andapa.

For the British, the Madagascar cam- paign was one of the odder successes of the second world war. Early in 1942, with armies reeling backwards in North Africa and the Far East, Allied strategists realised that Japanese submarines could do serious damage to military supply-lines round the Cape of Good Hope, since all ships used the Mozambique Channel between the east coast of Africa and the red island of Madagascar. The French colony had opted for Vichy in 1940, and Vichy had military treaties with imperial Japan. What Madagascar offered the Japanese navy was one of the world's great natural harbours in the northern tip of the island at Diego Suarez (now Antsiranana). To block a Japanese jump across the Indian Ocean, Churchill ordered the storming of Diego Suarez.

Operation Ironclad was planned and executed in seven weeks, and was a model for many combined landings to come, in North Africa, Italy and Normandy.

The initial invasion of 5 May 1942 was no walk-over. The Malagasy and Sene- galese defenders inflicted casualties: 121 killed, 305 wounded. And a Japanese two- man midget submarine later torpedoed the battleship HMS Ramillies in the middle of the harbour.

The Allied dead lie in the Diego Suarez British war cemetery. It's not far from the overgrown Vichy graves, but the contrast couldn't be greater. Behind the fence, under the sign of the sword in the cross, a kempt garden displays trim lawns round the beds of 315 headstones. There are ten sailors and 15 airmen among the soldiers. Walking slowly, ducking the circling sprinklers, I said each man's name aloud, from Gunner Bafiri Yobure of the East African Artillery to Sec- ond Lieutenant S.B. Black of the Seaforth Highlanders. On the grave of Private M. Faydherbe from Mauritius: Devant ma froide pierre passant, dis une priere, car ici je n'ai pas ami.' On a British 20-year-old's stone: 'He gave his all, his unfinished life.'

There's one Hindu, S. Palanee from Mau- ritius. Only Captain Genussow of the Green Howards, attached to the King's African Rifles, has the Star of David on his stone. There are many Muslims among the 132 East Africans who make up almost half the dead. Unsegregated from them, under their `Union is StrengthiEendrak Maak Mug' springbok badges, lie ten South Africans.

The clean-cut stones show that the assault brigade — the East Lancashire Regiment, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the Seaforth Highlanders and the Royal Welsh Fusiliers — took the brunt of the casualties on 5, 6 and 7 May 1942. Diego Suarez fell early on the seventh, after an amazing mid- night sortie by 50 Royal Marines off the destroyer Anthony, which had dashed past the guns into the harbour.

I read the livre d'or, the book of remem- brance, sitting under the bougainvillaea in the rich afternoon light. The men in this Commonwealth cemetery are not forgot- ten. Every November there is a Remem- brance Day service here.

The man who holds it is Monsignor Keith Benzies, the Anglican Bishop of Antsiranana, who lives off the rue de la Prison. When he came out on to his veran- da, he was wearing a short-sleeved purple shirt with pectoral cross, black trousers and black shoes. He has a fine, ascetic face and a quick smile. While we talked about the poppy-day services, in which all faiths are represented (though he worries about no one saying Kaddish for Captain Genus- sow), I met a succession of the halt and the lame: Claudette the seamstress who has been blind from birth, Therese the bare- foot ex-deaconess who lost an arm in a bus- crash, moustachioed Dominique in his wheelchair, once abandoned to crawl with withered legs. The bishop doesn't only look after the dead.

Keith John Benzies was born in Stepps, Lanarkshire, one of twins. When the boys were 17, their mother and younger brother flew out to see their father who was teaching in Nigeria. The return flight crashed, killing his mother and brother. Keith read modern languages at Glasgow, hoping to become a diplomat, but got religion and went as a French-speaking missionary to Madagascar. Six years, they said; he's stayed for 34.

In 1982 Keith Benzies was elected Bish- op of Antsiranana by his flock: unusual, as the previous two bishops had been black Bishop Benzies has survived chronic bil- harzia and even cerebral malaria (they flew him to England, raving). Now he's been diagnosed with Parkinson's. He can't use his left hand fully, and his left foot is numb. But numbness doesn't stop him walking. The parish can't run to a car, so the 62-year-old bishop walks everywhere. One place is 85 km in and 85 km out. He's tried every kind of footwear known to man. Flip-flops flop off and heavy boots are hopeless; the best are sandals with a heel strap and top buckle that let the water run out. No change since the New Testa- ment, then.

There is something called an Anglican cathedral in Diego Suarez, a dim barn of breeze-blocks and corrugated iron in a rough part of town. But already the build- ing is too small for the congregation of 400, and the bishop plans a new one behind his house.

He said with an innocent frankness that he'd been 'horrified' to read a description of himself in Helena Drysdale's 1991 travel book, Dancing with the Dead.

`Nothing wrong with it,' I said. 'Except perhaps your comments on police brutality.'

`That's just it,' he replied. 'If they'd read that, I'd probably have been deported.'

`But did you actually say those things?' `Oh, yes, it's all perfectly true. Just rather imprudent to print it.'

The nearby prison is still a hell-hole. The prisoners don't even have mattresses, in case they set fire to them. They sing softly behind the high wall.

`I once used to visit a parishioner who was in for drunken affray,' Bishop Benzies began with his quick smile. 'And there was a young lady who used to visit the prison at the same time. She wore perhaps a little too much make-up, and her skirt was rather on the short side. As a man of the world, you might understand the sort of young lady I mean? Well, some months later I was bidding farewell to the congre- gation outside the cathedral after even- song. You know the sort of area it's in. The young lady from the prison spotted me and came across the road, waving, in her short skirt and high heels. 'Bishop!' she shrieked. 'How lovely to meet you again! I haven't seen you for ages, and it used to be once a week!'

In three years the bishop retires, to a sim- ple house down the coast at Ambilobe. Keith Benzies will end his days in Madagas- car, where he has spent more than half his life doing good. But he still wants to raise that cathedral, 34 metres by 18 of cement blocks, by the mango tree in the yard.

Donations can be sent to: Mgr Keith J. Benzies, BP 278, (201) Antsiranana, Mada- gascar.

Previous page

Previous page