A lesson from the Castilians

Christopher Howse believes Salamanca could teach London a thing or two about squares

The pigeons certainly had to go, and the statues of generals are a red (Ken) her- ring. We were just about to hear Mr Ken Livingstone's plans for Trafalgar Square when, after his revocation of the licence of the last pigeon-food seller there, poor old Ken was escorted away by police to a place of safety out of reach of animal activists. A few days later, serious discussion of the future of the square was sidetracked by a flap about the statues of Generals Napier and Havelock.

This is the usual level of debate about the future of an open space that everyone still thinks of as being at the heart of Lon- don. It remains meanwhile fenced in by traffic, a noisy, dirty, rainswept round- about, difficult to cross on foot, haunted on cold Sunday afternoons by exhibitionist roller-bladers and used as a rendezvous by rioters or football supporters who want to throw things at policemen. Need it be like this?

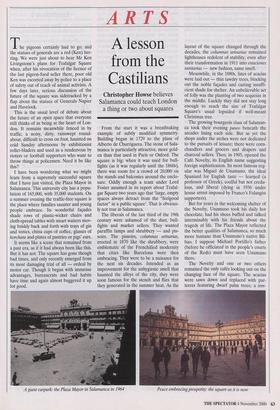

I have been wondering what we might learn from a supremely successful square that I have just visited, the Plaza Mayor in Salamanca. This university city has a popu- lation of 165,000, with 35,000 students. On a summer evening the traffic-free square is the place where families saunter and young people embrace. Its wonderful facades shade rows of plastic-wicker chairs and cloth-spread tables with smart waiters mov- ing briskly back and forth with trays of gin and tonics, china cups of coffee, glasses of horchata and plates of pastries or pigs' ears.

It seems like a scene that remained from a past era, as if it had always been like this. But it has not. The square has gone though bad times, and only recently emerged from its most damaging trial of all — ordeal by motor car. Though it began with immense advantages, bureaucrats and bad habits have time and again almost buggered it up for :wild. From the start it was a breathtaking example of subtly modified symmetry. Building began in 1729 to the plans of Alberto de Churriguera. The stone of Sala- manca is particularly attractive, more gold- en than that used in Paris or Oxford. The square is big: when it was used for bull- fights (as it was regularly until the 1860s), there was room for a crowd of 20,000 on the stands and balconies around the enclo- sure. Oddly enough a team under Lord Foster assumed in its report about Trafal- gar Square two years ago that `large, empty spaces always detract from the "feelgood factor" in a public square'. That is obvious- ly not true in Salamanca.

The liberals of the last third of the 19th century were ashamed of the dust, bull- fights and market sellers. They wanted paraffin lamps and shrubbery — and pis- soirs. The pissoirs, columnas urinarias, erected in 1870 like the shrubbery, were emblematic of the Frenchified modernity that cities like Barcelona were then embracing. They were to be a nuisance for the next six decades. Intended as an improvement for the unhygienic smell that haunted the alleys of the city, they were soon famous for the stench and flies that they generated in the summer heat. As the layout of the square changed through the decades, the columnas urinarias remained lighthouses redolent of stability, even after their transformation in 1911 into estaciones sanitarias — new fashion, same smell.

Meanwhile, in the 1880s, lines of acacias were laid out — thin tawdry trees, blocking out the noble facades and casting insuffi- cient shade for shelter. An unbelievable act of folly was the planting of two sequoias in the middle. Luckily they did not stay long enough to reach the size of Trafalgar Square's usual lopsided if well-meant Christmas tree.

The growing bourgeois class of Salaman- ca took their evening paseo beneath the arcades lining each side. But as yet the shops under the arches were not dedicated to the pursuits of leisure; there were corn- chandlers and grocers and drapers and charcoal sellers. Then, in 1905, opened the Café Novelty, its English name suggesting foreign sophistication. Its most famous reg- ular was Miguel de Unamuno, the ideal Spaniard for English taste — learned (a professor of Greek), soulful but not credu- lous, and liberal (dying in 1936 under house arrest imposed by Franco's Falangist supporters).

But for years in the welcoming shelter of the Novelty, Unamuno took his daily hot chocolate, had his shoes buffed and talked interminably with his friends about the tragedy of life. The Plaza Mayor reflected the better qualities of Salamanca, so much more humane than Unamuno's native Bil- bao. I suppose Michael Portillo's father (before he officiated in the people's courts of the Reds) must have seen Unamuno there.

The Novelty and one or two others remained the only cafés looking out on the changing face of the square. The acacias were sawn down and replaced with par- terres featuring dwarf palm trees; a tem- plete or bandstand was set up temporarily in 1906 and remained until 1930; the earli- est telephone exchange announced its ser- vices in giant letters on the Churrigueresque façade; motor cars replaced horse traffic circling the periphery.

The bittiness of the square was suddenly transformed thanks to a visit by Franco in 1954, when the caudillo received a doctor- ate honoris causa on the 700th anniversary of the founding of the university. Central funds were coughed up to repave the whole space, doing away with shrubs and wrought-iron railings. In that year there were only four cars per hundred popula- tion. Then came the economic miracle.

Within a decade the Plaza Mayor had become a giant carpark. Like Horseguards in London (or the space in front of the Louvre) its architectural shape was lost and its paving was soiled by oil leaks and exhaust stains. Those who opposed the car were told that the shops would be forced out of business if customers could not park. It was touch and go, but in 1970 a few stone benches were set up in the square and entry for cars prohibited.

Far from shops shutting, locations beneath the arcades became the most sought after for luxury items. By day the cafés extended their rafts of tables ever fur- ther to each side. Spain is lucky in its street life because, unlike the English high street, an abandoned desert haunted only by drug takers and a few youths on children's bicy- cles, Spanish shops stay open till nine and bars are visited by families with children till after midnight. And Spaniards live in the centres of cities, not in distant suburbs reached by the 5.13 train. So in the central, open, trafficless Plaza Mayor peace embraced prosperity. But a few flies remained in the ointment.

The flood of tourists that reinforced the Spanish economy in the 1970s brought for- eign bad manners. Tourists treated the out- door café seats like the beach, exposing their sunburnt flab. The stylish and polite Salamantine population came to treasure the wet, cold, windy days of winter when a scarf-wrapped stroll under the stone arcades would end in a warm circle of friends and cigarette smoke, unjostled by tourists. But even the native populace allow, with inexplicable tolerance, periodic open-air rock concerts of throbbing loud- ness into the small hours.

In London Mr Livingstone is toying with ideas of outside entertainment, with large screens, perhaps, as with Opera in the Park. One trouble is that it rains much more in London than in Salamanca. And although the pavements of Westminster are stained with fat from pizza slices and burgers, there is nowhere to sit and eat and drink on the perimeter of Trafalgar Square. Already 'heritage wardens' are moving on unlicensed hotdog sellers with their rancid fare. But will licensed outlets be better?

But the traffic remains the great bone of contention. Westminster City Council has huffily handed over responsibility for Trafalgar Square's traffic plan to the Mayor of London. He favours at least the closure on the northern roadway between the National Gallery and the central square. But where are the cars to go? This is not Salamanca, the size of Croydon and sur- rounded by open country; London is a fun- nel into which pours a daily cascade of cars.

Other pedestrianised squares in London are not good precedents. Leicester Square is sleazy beyond belief, good only for a teenager's first vomit of vodka. Bedford Square is dead because there are no shops or cafés lining it. God knows what would happen to Trafalgar Square if it tried to emulate Covent Garden Piazza. That would require some retail outlets, and the opportunities are limited in Trafalgar Square by the lowering presence of South Africa House and Canada House to the east and west.

I wonder whether an arcade of shops could be built on the elevated north side, below the level of the National Gallery? Or if there could be a window-fronted restau- rant there, reachable from the Gallery. Yet it is easy to think what a bodge our estab- lishment architects might make of that.

It is going to take more to solve the problem than the Foster think-tank's idea of a new flight of steps up from the square to the National Gallery. But perhaps Lon- doners just cannot make squares work because they do not behave like Castilians.

Christopher Howse is Obituaries Editor of the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page