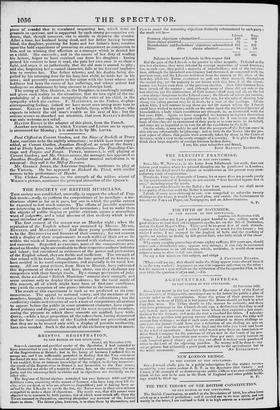

THE TRUE THEORY OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION. TO THE EDITOR

OF TINE SPECTATOR. The British Constitution, as settled at the Revolution of 16'39, has often been cried up as a model of perfection : and if carried out in its true spirit, and not merely in the letter, I am inclined to hold it in high esteem as a means of good

• government ; but it is only by • free and liberal interpretation of its spirit, and bt a fearless departure from the letter whenever it shall clash with the spitit, that such can be the case. The mere bald theory of checks and ba- lances, arising out of its tripartite composition of King, Lords, and Commons, has been so ably exposed, and indeed demolished, in the article " Government"

in the Supplement to the Encyclopedia Britanniea, that it were a work of supererogation to discuss that point,—raking up the ashes of the dead : but it appears to me that there is nevertheless a principle of vitality in the British Constitution, which, if duly attended to and fostered, may yet prove it to be capable of answering its professed end of good government.

• It has been an avowed axiom of the defenders of the British Constitution as by law establiahed, that for every wrong committed a remedy was provided by it,—which is only saying in other words, that IRILESVONSIBLE POWER, the

power to commit wrong without a remedy, is not a component part of the Con- stitution. We have then arrived at a great principle admitted by all the writers

and speakers in favour of that monument of human wisdom called the British

Constitution,—namely, that it is reared on the basis of Responsible Power. This may be the stone that the builders rejected, but it is nevertheless DOW be- come the chief corner-stone : and it is the main object of these lines to show,

that the community is entitled, in the true spirit and theory of the Constitu- tion, to render " La Charte." of Responsible Power " une graude verit6."

What is now the actual condition of the State Machine? how does it work ? is there any part of it in which the antagonist and anti- Constitutional prin. ciple of Irresponsible Power is seen in action ?—for if there be, it is clearly

the right and the duty of the community so to alter and amend that working as to bring it under the operation of its true principle,--in other words, to

right the existing wrong. Nor will it avail any one to say, that we are not entitled to depart from the letter of the Constitution (if such should happen to be neeessary) in order to get at the spirit. It may have happened, nay it has happened, that at the time of the settlement of the Constitution in 1668, few, if any, (of those who were engaged in this task were aware how it would work, Of in what hands the powers of government were really deposited ; never- theless, it wis laid down as the professed object and the principle of that ar- rangentent, that Irresponsible Power should exist nowhere — that nowhere should there be the means of wrongdoing without an adequate remedy. It; then, it can be clearly shown, that in the actual working ot the system of go- vernment, as at present existing, there is a departure from this its true theory, we are entitled to modify that system so as to bring all its parts into harmony, and thus work together towards the attainment of the real end—the welfare of all.

Now what evidence do the last five or six years supply to enable us to arrive at a c .rtain conclusion on this point. At the commencement of the period se- lected, (which might have been extended much further backward.,) we wit- nessed earnest, repeated, and almost universal petitioning, from all quarters and from every curlier of the kingdom, praying that the endless outrages on the Con-titntion, arising out of the corrupt mode in which the third branch of tloe Legislative Body was put together. might be stopped. These prayers were ad- dressed to both Houses; but would have remained unattended to in both, but from " the pressine front without," which forced the Lower House by the most unparalleled exertions to put itself somewhat more in order, and to reecho in some degree the national voice. This, however, was only accomplished by the application (though very imperfectly) of the great constitutional prin- ciple of Responsibility. When the change had proceeded so far as to overcome the resistance in the Commons, what did we witness ?—why, nothing less than a coop d'etat, on the part of the Nation, before the other House could he brought to see its actual position, on the brink of a precipice, on the edge of which it has ever since been howerhog ! I lappily the evil was got over for the time; but only by the application of an on egular and very unconstitutional power, which, though it may sometimes be necessary, it is always hazardous to call into action, and ought never to be resorted to but in cases of the extremest urgency. Well, it was thought and fully expected by many, that this unusual demonstration would render all similar appeals unnecessary ; and that the errors which had been committed in the attempt to retain irresponsible power would be seen, acknowledged, and no longer persisted in. But what did the very first session of the Reformed Pal liament show ?—why just the reverse of all that was reasonably hoped for: all the good measures of the Government were rejected by the Upper House, all the bad and equivocal ones adopted. To such a pitch was this carried, that the supporters of the Ministry in the Lower House dwindled by degrees to a bare majority ; and the exasperation in the public mind rose to that height, that the party who formed a large majority in the Upper House was emboldened to strike down the Ministry at a blow, to put themselves into the saddle, and to call a fresh Parliament ; in which they suc- ceeded in reducing the majority of their opponents so considerably, as to leave it for some time a matter of doubt if they could again be ousted. When, how- ever, at last the Whig Ministry was reseated, what was the line of conduct pursued in the Upper House? It is fresh in every one's recollection, and it is therefore unnecessary to go much into detail; but the character of the Opposi- tion was such as to evince an utter recklessness of consequences. The Irish Clergy were doomed to remain, as hitherto, between the two fires of an exaspe- rated population on the one hand and a remorseless party-spirit on the other ; from the effects of which they have only been temporarily saved by an act having been hurried through both Houses at the close of the session to prevent a former act being enforced against them ! Bills were thrown out on the most frivolous and paltry pretences,—one on the ground of having been advocated by O'Connell; other bills were disfigured and mutilated so as to be scarcely recognizable; in short, all the freaks and pranks of a set of madmen were enacted. Now what does all this prove, but that the parties so acting felt themselves accountable to no one for their conduct—felt themselves beyond the reach of the principle of Responsibility; for had there been the smallest restraint upon them of this kind, it is quite certain that they could not so have demeaned themselves. Is there not, then, a case made out—that irresponsible power has crept into the Constitution; and that it must be removed, as being contrary to its true spirit, and to the public welfare? Here is clearly a wrong committed, for which a remedy must be found.

It is to no purpose to say tgat the power above described has always existed, and that we have therefore no right to abrogate or take it away : this is no answer ; for the abuse, or rather the usurpation, existed lung before it was clearly perceived, and circumstances only have brought it more prominently forward than before. The period is now arrived when this anomaly in the Constitution is felt, and felt as a great and insupportable grievance: it is clearly seen that the system is no longer capable of working in harmony with its several parts ; and there is therefore now only the alternative of restoring this harmony, or, if that he not practicable, of breaking it up altogether. To me it appears we are not yet reduced to the latter horn of the dilemma, but that there is still a way open, and that in strict conformity with the true spirit and theory of the Constitution,—namely, by restoring (or if it never really exis:ed thew litfi,re, of introducing) the principle of Responsibility into it. ir scarcely neeisrary to add, that this is only to be attained by making the Upper llous:e amenable in its public conduct, in the same way as is applied to all functional ies s' indatly circumstanced,—namely, periodical elections, by a constituency renim ed as fir as possible out of the reach of any sinister bias. It is not net;essary here to no into M is the m'4us del gandi ; it is sufficient for the present norpose 'to point out what is wanted—not how to to :t. J. R. T.

Previous page

Previous page