'A COMPLETE LACK OF CONFIDENCE'

Christopher Fildes talks to Nigel Lawson

about the sad state of the economy, and how we got into it

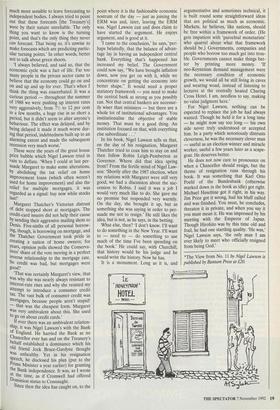

WHEN Nigel Lawson resigned from the Government, I thought that lunch might cheer him up. I found him suffering from political withdrawal symptoms, but resilient. 'I thought I would write a book,' he said. 'What sort of a book do you think I should write?' I had just read and rel- ished Denis Healey's fat volume of mem- oirs, and suggested one to match. 'Well, yes, I've read Denis's book, it is good, but — put it this way, Christopher — if you happened to be made Chancellor of the Exchequer, and you looked in Denis's book to see how to do it, it wouldn't be much help.'

That was the test he set himself, and now, three years later, out comes his own extraordinary book*. It would not, he says, have been considered a long book in Vic- torian times, when viceroys got two-decker biographies, but if you dropped it on your toe, it would hurt. He has written, as he explains, a chancellorial memoir.

To be Chancellor was, after all, the one post in government Nigel Lawson had always coveted: 'The whole of my previous professional life had in effect been a preparation for this.' Most professional politicians move more or less happily from department to department. James Callaghan, chatting to the Tory Chancellor beside the Cenotaph on Remembrance Day, recommended the Foreign Office: 'It's a doddle,' he said. It did not tempt Nigel Lawson, and indeed nothing did. He disclaimed any ambition of being Prime Minister; he never bothered to build up any political faction behind him; he stuck to his guns as Chancellor for more than seven years until all ended in bitterness and resignation.

He was, we can now see, the first of the Conservative Party's casualties in its unending war over Europe. That is ironic, because he was not and is not a Euro- enthusiast. The exchange rate mechanism, his casus belli with Margaret Thatcher, was to his mind the least bad solution to a domestic problem — the need for a stan- dard of monetary discipline. In the week before he resigned, he talked to me about the ERM's promoters. Some of them, he said, thought it wouldn't hurt at all, some

of them thought it would hurt very much, both thought that these would be good things, and he didn't agree with either.

All the same, he had been pressing to join for four years, trying and failing to convince Margaret Thatcher in November 1985. Her attitude was: I'm against and the motion's lost. He calls this the saddest event of his time as Chancellor, and the greatest missed opportunity.

Supposing, though, that we had taken it? After all, we joined, in the end, and have been forced out again, with our tail between our legs. Why would joining earli- er have made any difference? I put the question to him last week as we sat togeth- er in his new home in the Northampton- shire village of Newn ham.

'Of course,' he says, 'there'd have had to be some realignment in 1986, following the oil price collapse. As it was, the pound went down far too far in '86 — outside the ERM it was impossible to contain it — and, looking back, sowed the seeds of the inflationary pressure which was subse- quently to emerge.

'By the time we got to the immense dif-

ficulties of the past two years — a combi- nation of three things: a prolonged reces- sion, the mishandling by the German government of the economic consequences of reunification, and the consequent action of the Bundesbank to cope with recession — on top of all this came the quite gratu- itous strain placed on the system by the move towards European monetary union. This severely damaged the ERM. The ERM, instead of being seen as something in itself, a regional Bretton Woods agree- ment, was seen as an ephemeral ante- chamber to monetary union. So doubts about EMU played back on to the ERM. . . This ludicrous idea that you could progressively harden the ERM, glid- ing smoothly to monetary union — you couldn't do that any more than you could change from an elephant into a hippopota- mus.

'Nevertheless, had we entered in 1985 we'd have had five years' experience, the authorities would have had far greater experience of how to operate within the system. By that time, sterling's membership of the system would have had a high degree of credibility. What happened in fact? We'd set sail for the first time with our L- plates still tied on our backs in a force 8 gale — which is not ideal. We had said that we would join when the time was right. We joined when the time could not have been more wrong.'

In 1985, Nigel Lawson sent a secret mis- sion to the Bundesbank to agree provision- al terms for entry. 'It's quite clear that if this is going to work, you've got to have the Bundesbank in full agreement with the rates, and also the support mechanism. My impression is that in 1990 we chose the rate at which we went in, and merely

informed the Bundesbank. That was not a sensible thing to do; it was a bad way to start. It's folly operationally to have a rate which the Germans have doubts about. Sooner or later the market's going to realise it — though I think the Germans' careless talk was very naughty. 'But there needed to be realignment. The Germans wanted one — and the wider the better. . . but sometimes you have to accept the second best. The Government allowed themselves to be painted into a corner. One of the problems was that theY were all the time saying, "If need be we 11 raise interest rates," but if you go on talk- ing in these terms and don't take any action, the markets will draw certain con- clusions.'

So we got the worst of all worlds: 'The problem in the economy now is a complete lack of confidence.' The confidence Nigel Lawson created as Chancellor proved, for a while, too strong for him, and was a part of his troubles as the Lawson boom turned into the Lawson blip. 'I was myself taken by surprise at the length of the upturn,' he says. 'I expected It_ to turn much earlier, on the basis, not Of forecasts, but of historical experience. It s much more sensible to leave forecasting to independent bodies. I always tried to point out that these forecasts [the Treasury's] were by their nature unreliable. The only thing you want to know is the turning point, and that's the only thing they never can forecast. That being so, it's unwise to make forecasts which are predicting partic- ular turning points.' In other words, better not to talk about green shoots.

`I always believed, and said so, that the economic cycle was a fact of life. Far too many people in the private sector came to believe that the economy could go on and on and up and up for ever. That's when I think the thing was exacerbated. It was a curious period — throughout the summer of 1988 we were pushing up interest rates very aggressively, from 772 to 12 per cent in a few months, a huge rise in so short a period, but it didn't seem to alter anyone's behaviour. The effect was delayed, and by being delayed it made it much worse dur- ing that period, indebtedness built up to an alarming extent and made the subsequent recession very much worse.' These were the years of the great house Price bubble which Nigel Lawson tried in vain to deflate. 'When I could at last per- suade Margaret to make some alterations, Y abolishing the tax relief on home improvement loans (which often weren't used for home improvement) and also the relief for multiple mortgages, it was regarded as a signal: buy now while stocks last!'

Margaret Thatcher's Victorian distrust of debt stopped short at mortgages. The credit-card issuers did not help their cause by sending their aggressive mailing shots to penis. Five-sixths of all personal borrow- ing, though, is borrowing on mortgage, and the Thatcher Government took pride in creating a nation of home owners; for Years, opinion polls showed the Conserva- tives' share of the vote moving in a perfect inverse relationship to the mortgage rate. So credit was bad, but mortgages were good?

'That was certainly Margaret's view, that !vas why she was nearly always resistant to interest-rate rises and why she resisted my attempt to introduce a consumer credit tax, The vast bulk of consumer credit was mortgages, because people aren't stupid! — that was the cheapest form. Margaret was very ambivalent about this. She used to go on about credit cards.' If ever there was an ambivalent relation- ship, it was Nigel Lawson's with the Bank of England. He harried the Bank as no Chancellor ever has and on the Treasury's behalf established a dominance which his old friend Jock Bruce-Gardyne thought was unhealthy. Yet in his resignation Speech, he disclosed his plan (put to the Prime Minister a year earlier) for granting the Bank independence. It was, as I wrote at the time, as if Cromwell had offered Dominion status to Connaught. Since then the idea has caught on, to the point where it is the fashionable economic nostrum of the day — just as joining the ERM was and, later, leaving the ERM was. Nigel Lawson can and does claim to have started the argument. He enjoys argument, and is good at it.

`I came to the conclusion,' he says, 'per- haps belatedly, that the balance of advan- tage lay in having an independent central bank. Everything that's happened has increased my belief. The Government could now say, "We have brought inflation down, now you get on with it, while we concentrate on getting the economy into better shape." It would need a proper statutory framework — you need to make the central bank as strong as you possibly can. Not that central bankers are necessar- ily wiser than ministers — but there are a whole lot of institutional advantages. You institutionalise the objective of stable money. That must be a good thing. An institution focused on that, with everything else subordinate. .

In his book, Nigel Lawson tells us that, on the day of his resignation, Margaret Thatcher tried to coax him to stay on and then follow Robin Leigh-Pemberton as Governor. Where did that idea spring from? From the fertile mind of Nigel Law- son: `Shortly after the 1987 election, when my relations with Margaret were still very good, we had a discussion about the suc- cession to Robin. I said it was a job I would very much like to do. She gave me no promise but responded very warmly. On the day, she brought it up, but as something she was saying in order to per- suade me not to resign.' He still likes the idea, but is not, as he says, in the betting. What else, then? `I don't know. I'll want to do something in the New Year. I'll want to — need to — do something to use much of the time I've been spending on the book.' He could say, with Churchill, that history would be his judge and he would write the history. Now he has.

It is a monument. Long as it is, and argumentative and sometimes technical, it is built round some straightforward ideas that are political as much as economic. Markets, he believes, like nations, should be free within a framework of order. (He gets impatient with `parochial monetarists' who quarrel about what that framework should be.) Governments, companies and people who borrow too much get into trou- ble. Governments cannot make things bet- ter by printing more money. `If neo-Keynesian demand management were the necessary condition of economic growth, we would all be still living in caves and wearing woad, instead of listening to lectures at the centrally heated Charing Cross Hotel. I am, needless to say, making no value judgment here.'

For Nigel Lawson, nothing can be expected to replace the job he had always wanted. Though he held it for a long time — he might now say too long — his own side never tru!y understood or accepted him. In a party which notoriously distrusts cleverness, he was the necessary clever man — useful as an election winner and miracle worker, useful a few years later as a scape- goat. He deserves better. He does not now care to pronounce on when a Chancellor should resign, but the theme of resignation runs through his book. It was something that Karl Otto Poehl of the Bundesbank (otherwise marked down in the book as idle) got right. Michael Heseltine got it right, in his way. Jim Prior got it wrong, had his bluff called and was finished. You must, he concludes, threaten it in private, and when you say it you must mean it. He was impressed by his meeting with the Emperor of Japan. Though Hirohito was by this time old and frail, he had one startling quality. 'He was,' Nigel Lawson says, 'the only man I am ever likely to meet who officially resigned from being God.'

*The View from No. 11 by Nigel Lawson is published by Bantam Press at £20.

Previous page

Previous page