Exhibitions

From Gainsborough to Constable: the Emergence of Naturalism in British Painting 1750-1810 (Gainsborough's House, Sudbury, till 13 October)

True to nature

John Henshall

If one over-riding impression emerges from this ambitious look at the early influ- ences upon and gradual development of John Constable, it is how painfully lacking in confidence he could be in establishing himself as a painter at all, never mind as the future creator of the classic works for which we know him today. There were false starts, dubious influences and sometimes startling instances of self-doubt to be bat- tled with and vanquished. Constable's was a very different story from the compara- tively effortless development of men like Gainsborough, Turner and others, who early on displayed an easier, more eclectic talent and acted on it swiftly.

Constable was handicapped, albeit in a positive manner, by his family background. His father, Golding Constable, was a pros- perous miller in Suffolk's Stour valley, engaged in a healthy waterborne trade with London. It was generally expected that

John would eventually take over the family firm. Whilst his gradual veering away from the avenues of commerce seems to have created no overt friction, it is difficult not to imagine that the young man's early sketching expeditions with his talented, if untutored companion, John Dunthorne, would have been seen as a phase which would pass in due course.

Then there are the essentially self- imposed constraints under which the young Constable laboured. His early copies of works like 'Christ's Charge to Peter' (1795), one of a set of three made after Nicholas Dorigny's engravings of Raphael's tapestry cartoons, which he proudly showed to his mentor and family friend Sir George Beaumont, are unlikely seriously to have impressed the baronet. However, Consta- ble made more progress shortly afterwards when he was introduced, again through family connections, to 'Antiquity' Smith, who led the young artist to borrow and copy more etchings by Ruisdael, Hobbema, Waterloo and others.

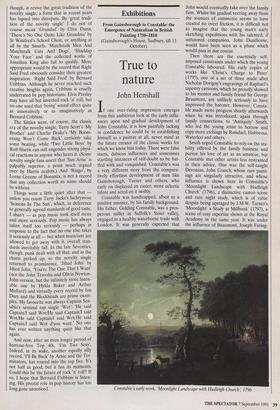

Smith urged Constable to rely on the sta- bility offered by the family business and pursue his love of art as an amateur, but Constable met other artists less restrained in their advice. One was the self-taught Devonian, John Cranch, whose rare paint- ings are singularly attractive, and whose influence is shown here in Constable's 'Moonlight Landscape with Hadleigh Church' (1796), a distinctive cameo scene and rare night study, which is of value despite being upstaged by J.M.W. Turner's 'Moonlight: a Study at Millbank' (1797), a scene of easy expertise shown at the Royal Academy in the same year. It was under the influence of Beaumont, Joseph Faring- Constable's early work, 'Moonlight Landscape with Hadleigh Church', 1796 ton and later Ramsey Richard Reinagle that Constable was able to resist family pressures and arrive in London in 1800 for a successful first year in his own right.

There he spent his time painting, copying and soaking up the artistic gossip of the day. This experience led to his exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1802 of the Gains- boroughesque 'Edge of a Wood', which Farington found 'rather too cold', advising its young creator to study nature more and 'particular art' less. By the exhibition of 1805, Constable was well on the way to doing this, and his 'Landscape — Moon- light' (c. 1805) led Farington to conclude that the young man would become the leader in British landscape art.

In between his London stays, Constable spent time back in Suffolk and the north Midlands. Always he sought truth in nature as paramount. Of Gainsborough he remarked that his first pictures were his best, '[his] latter so wide of nature'. He wrote to Dunthorne of the Royal Academy exhibition of 1802 that 'the great vice of the present day is bravura, an attempt at some- thing beyond the truth', adding that, 'Truth (in all things) only will last and can have just claims on posterity'. It is certainly truth, albeit Constable's somewhat arcadi- an, 'older England' version of it, which shines down the years through 'The Hay- wain', 'Flatford Lock' and the rest.

Constable was sometimes sidetracked by the influence of undistinguished painters like George Smith, whose 'Winter Scene', c. 1765, he first idealised but later regarded as pastiche (Smith could have made a rea- sonable living as a designer of upmarket Christmas cards today). But Gainsbor- ough's 'Landscape with Pool' (c. 1746-7) and 'Wooded Landscape with Cattle' (1782) and Reinagle's 'Dedham in Flood' (1799) provided truer models, and slowly the young Constable came into his own with 'The Harvest Field' (c. 1797), 'Strat- ford St Mary from the Coombs' (c. 1800-1) and 'Stour Estuary' (1804). Indeed, this dis- parate exhibition is remarkably successful at showing the perhaps unusual number of influences — both good and dubious — which were to make their mark in the tech- nique of a man destined to become a mas- ter of English art.

A deliciously surreal television commer- cial a few years ago showed a party of pre- sumably American tourists being led round an art gallery by a keeper of the old school. Halfway up a flight of stairs they were con- fronted by an enormous portrait with a receptacle full of sand beneath it. 'Golly, gee,' bawled one blue-rinsed fright, Is that a real Van Garffr To which the attendant replied punctiliously, 'No, Madam, that is a fire bucket.' In any exhibition on this scale we are bound to get the odd metaphorical fire bucket. It is to the great credit of the curators that here they are few and far between. The exhibition will transfer to the Leger Galleries, London Wl, from 14 November to 4 December.

Previous page

Previous page