The entrepreneur’s art: buying, building, selling

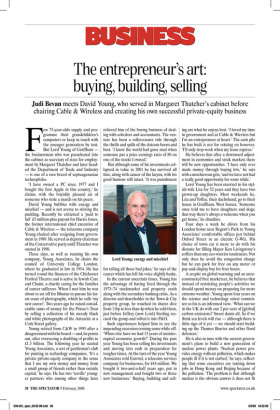

Judi Bevan meets David Young, who served in Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet before chairing Cable & Wireless and creating his own successful private-equity business Few 75-year-olds supply and programme their grandchildren’s computers or keep in touch with the younger generation by text. But Lord Young of Graffham — the businessman who was parachuted into the cabinet as secretary of state for employment by Margaret Thatcher and later headed the Department of Trade and Industry — is one of a rare breed of septuagenarian technophiles.

‘I have owned a PC since 1977 and I bought the first Apple in this country,’ he claims, with the boyishly pleased air of someone who stole a march on his peers.

David Young bubbles with energy and mischief — and is not averse to stirring the pudding. Recently he criticised a ‘paid to fail’ £5 million-plus payout for Harris Jones, the former international chief executive of Cable & Wireless — the telecoms company Young chaired after resigning from government in 1989. He served as deputy chairman of the Conservative party until Thatcher was ousted in 1990.

These days, as well as running his own company, Young Associates, he chairs the council of University College London, where he graduated in law in 1954. He has turned round the finances of the Chichester Festival Theatre and is active in Jewish Care and Chaim, a charity caring for the families of cancer sufferers. When I met him he was about to set off for Bhutan to pursue his latest craze of photography, which he calls ‘my new career’. Two years ago he raised considerable sums of money for the Prince’s Trust by selling a collection of his moody black and white photographs of the Antarctic at a Cork Street gallery.

Young retired from C&W in 1995 after a disagreement with the board — and, he points out, after overseeing a doubling of profits to £1.3 billion. The following year he started Young Associates, a sort of gentleman’s club for punting in technology companies. ‘It’s a private private-equity company in the sense that I use my own money and money from a small group of friends rather than outside capital,’ he says. He has two ‘terrific’ younger partners who among other things have relieved him of the boring business of dealing with solicitors and accountants. The venture has been a rollercoaster ride through the thrills and spills of the dotcom boom and bust. ‘I knew the world had gone mad when someone put a price earnings ratio of 80 on one of the stocks I owned.’ But although some of his investments collapsed in value in 2001 he has survived all that, along with cancer of the larynx, with his good humour still intact. ‘It was punishment for telling all those bad jokes,’ he says of the cancer which has left his voice slightly husky.

In the current uncertain times, Young has the advantage of having lived through the 1973–74 stockmarket and property crash along with the secondary banking crisis. As a director and shareholder in the Town & City property group, he watched its shares dive from 116p to less than 4p when he sold them, just before Jeffrey (now Lord) Sterling rescued the group and rolled it into P&O.

Such experiences helped him to see the impending recession coming some while off. ‘When else have we had 13 years of uninterrupted economic growth?’ During the past year Young has been selling his investments and moving into cash in preparation for tougher times. At the turn of the year Young Associates sold Eurotel, a telecoms services company for businesses, for £44 million. We bought it two-and-a-half years ago, put in new management and bought two or three new businesses.’ Buying, building and sell ing are what he enjoys best. ‘I loved my time in government and at Cable & Wireless but I’m an entrepreneur at heart.’ The cash pile he has built is not for retiring on however. ‘I’ll only stop work when my lease expires.’ He believes that after a downward adjustment in economies and stock markets there will be new opportunities. ‘I have only ever made money through buying low,’ he says with a mischievous grin, ‘and we have not had a really good opportunity for some while.’ Lord Young has been married to his stylish wife Lita for 52 years and they have two grown-up daughters. Most weekends he, Lita and Toffee, their dachshund, go to their house in Graffham, West Sussex. ‘Someone once told me to have daughters and dogs; that way there’s always a welcome when you get home,’ he chuckles.

Four days a week he drives from his London home near Regent’s Park to Young Associates’ comfortable offices just behind Oxford Street in an electric G-Wiz. His choice of town car is more to do with his distaste for filling Mayor Ken Livingstone’s coffers than any eco-warrior tendencies. Not only does he avoid the congestion charge but he can park for free on any meter or pay-and-display bay for four hours.

A sceptic on global warming and an unreconstructed free marketeer, he believes that instead of restricting people’s activities we should spend money on preparing for more extreme weather. Young spent four years on the science and technology select committee so his is an informed view. ‘What can we in the UK do with our 2 per cent of [global] carbon emissions? Sweet damn all. So if we think sea levels will rise — although there is little sign of it yet — we should start building up the Thames Barrier and other flood defences.’ He is also in tune with the current government’s plans to build a new generation of nuclear power plants. ‘Nuclear power provides energy without pollution, which makes people ill if it is not curbed,’ he says, reflecting that some executives are turning down jobs in Hong Kong and Beijing because of the pollution. ‘The problem is that although nuclear is the obvious answer it does not fit the agenda of the people who are worried about global warming. Unfortunately, the anti-nuclear and the global warming lobby are mainly the same people.’ But as an erstwhile Thatcherite, Young is naturally out of tune with most of this government’s other policies. The Northern Rock scandal appals him and he lays the blame firmly at the door of Gordon Brown and ‘this overcomplicated tripartite thing’ — the division of responsibility between the Bank of England, the Financial Services Authority and the Treasury. ‘Under the old system nobody would have known about the problem. The Bank of England would have rung up one of the old joint-stock banks and offered them some help to take Northern Rock over.’ As a former member of Business for Sterling, which lobbied hard to keep Britain out of the euro, his line on Europe has hardened in the last five years. ‘At Business for Sterling we used to say there would be a £10 fine for anyone who said they wanted to leave Europe altogether, but now I believe we would have a much better relationship with Europe if we were part of the Free Trade Area.’ His view is that the continental Code Napoleon legal system is too different from Anglo-American common law to put the two together.

Although Young feels that Thatcherite policies did not pay enough attention to the disadvantaged, he applauds the change in social attitudes towards entrepreneurs that the era kick-started. He learned his first lessons in wealth creation as a protégé of the great entrepreneur Sir Isaac Wolfson — as indeed did Jeffrey Sterling. But when he left Wolfson’s Great Universal Stores to set up his own industrial property business, Eldonwall, in 1961, he hardly dared tell his friends because making money was deemed to be only marginally different to theft. Even in the 1980s he found it difficult to persuade graduates to work for themselves. ‘Nowadays you see and hear these bright, clever, ingenious people dreaming up new financial products, starting businesses, developing technology. The Conservatives gave people this wonderful opportunity to prosper.’ Young believes, by the way, that the next new, new thing to come from these kinds of individuals will be wireless-connected internet television, giving us any programme or film we want any time we want it. Doubtless he will be among the first to own one.

Previous page

Previous page