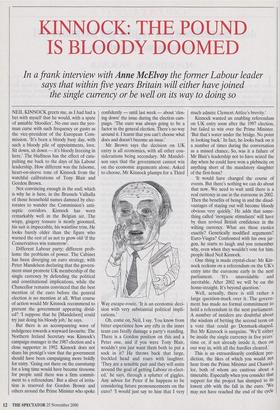

KINNOCK: THE POUND IS BLOODY DOOMED

says that within five years Britain will either have joined the single currency or be well on its way to doing so

NEIL KINNOCK greets me, as I had had a bet with myself that he would, with a spate of amiable 'bloodies'. No one uses the yeo- man curse with such frequency or gusto as the vice-president of the European Com- mission. 'It's been a bloody busy day, with such a bloody pile of appointments, love. Sit down, sit down — it's bloody freezing in here.' The bluffness has the effect of cata- pulting me back to the days of his Labour leadership. How different was the fulsome, heart-on-sleeve tone of Kinnock from the watchful calibrations of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

Not convincing enough in the end; which is why he is here, in the Brussels Valhalla of those household names damned by elec- torates to wander the Commission's anti- septic corridors. Kinnock has worn remarkably well in the Belgian air. The wispy, gingery tonsure is neatly groomed, his suit is impeccable, his waistline trim. He looks barely older than the figure who warned the rest of us not to grow old 'if the Conservatives win tomorrow'.

Different Labour party; different prob- lems: the problems of power. The Cabinet has been diverging on euro strategy, with Peter Mandelson declaring that the govern- ment must promote UK membership of the single currency by defending the political and constitutional implications, while the Chancellor remains convinced that the best mention of the euro before the general election is no mention at all. What course of action would Mr Kinnock recommend to prevent the government appearing divid- ed? 'I suppose that he [Mandelson] could try just doing his bloody job,' he says.

But there is an accompanying wave of indulgence towards a wayward favourite. The Northern Ireland Secretary was Kinnock's campaign manager in the 1987 election and a close supporter in 1992. Kinnock does not share his proteges view that the government should have been campaigning more boldly for entry. 'Going out there on the eurostump for a long time would have become tiresome for people until there was a firm commit- ment to a referendum.' But a sliver of irrita- tion is reserved for Gordon Brown and others around the Prime Minister who spoke confidently — until last week — about 'clos- ing down' the issue during the election cam- paign. The euro was always going to be a factor in the general election. There's no way around it. I learnt that you can't choose what does and doesn't become an issue.'

Mr Brown says the decision on UK entry is all economics, with all other con- siderations being secondary. Mr Mandel- son says that the government cannot win on the economic arguments alone. Asked to choose, Mr Kinnock plumps for a Third Way escape-route. 'It is an economic deci- sion with very substantial political impli- cations.'

Oh, come on, Neil, I say. You know from bitter experience how any rifts in the inner team can fatally damage a party's standing. There is a Gordon position on this and a Peter one, and if you were Tony Blair, wouldn't you just want them both to put a sock in it? He throws back that large, freckled head and roars with laughter. `They are a sensible pair and they will unite around the goal of getting Labour re-elect- ed,' he says, through a splutter of giggles. Any advice for Peter if he happens to be considering future pronouncements on the euro? 'I would just say to him that I very much admire Clement Attlee's brevity.'

Kinnock wanted an enabling referendum on UK entry soon after the 1997 election, but failed to win over the Prime Minister. `But that's water under the bridge. No point in looking back.' In fact, he looks back on it a number of times during the conversation as a missed chance. So, was it a failure of Mr Blair's leadership not to have seized the day when he could have won a plebiscite on anything short of the mandatory slaughter of the first-born?

`It would have changed the course of events. But there's nothing we can do about that now. We need to wait until there is a real currency in use in the eurozone in 2002. Then the benefits of being in and the disad- vantages of staying out will become bloody obvious very quickly.' He adds that some- thing called 'inorganic stimulants' will have by then revived British confidence in the wilting currency. What are these exotica exactly? Genetically modified arguments? Euro-Viagra? Confronted with his own jar- gon, he starts to laugh and you remember why, even when they wouldn't vote for him, people liked Neil Kinnock.

One thing is made crystal-clear: Mr Kin- nock reckons on a referendum on the UK's entry into the eurozone early in the next parliament. 'It's unavoidable and inevitable. After 2002 we will be on the home-straight. It's beyond question.'

Well, actually, there is still rather a large question-mark over it. The govern- ment has made no formal commitment to hold a referendum in the next parliament. A number of insiders are doubtful about the wisdom of betting the second term on a vote that could go Denmark-shaped. But Mr Kinnock is sanguine. 'We'll either be inside the single currency in five years' time or, if not already inside it, then on our way in, with all the hurdles cleared.'

This is an extraordinarily confident pre- diction, the likes of which you would not hear from the Prime Minister and Chancel- lor, both of whom are cautious about a timetable. Especially when you consider that support for the project has slumped to its lowest ebb with the fall in the euro. 'We may not have reached the end of the cycle yet,' Kinnock admits. He even refuses to rule out a further drop in the currency's waning value before the professional opti- mist reasserts itself. `But the pound and the euro are heading towards the outer edge of their practicality. That has to change.' In the meantime, Mr Blair has been talk- ing fluent European in his Warsaw and Mansion House speeches, while reassuring us that he would not like to join the single currency right now. But can the UK be `fully engaged' on such choosy terms? 'I would not believe that we were fulfilling our potential for influence, no.' As the government vacillates on how forthright it should be, a proxy war has broken out to fill up the airtime — against the evils of the Eurosceptic press. Mr Kin- nock launched it last month with a furious attack on the 'toxic levels' of 'serial distor- tion'. Robin Cook followed last week, with a dressing-down to doubters whom he condemned as unenlightened and per- verse, unlike 'patriotic' pro-Europeans. So come on, name the guilty papers, then. `The Mail is the worst, ahead of the Sun which is at least trying to have fun — only it is not so funny when it turns into ram- pant xenophobia.' The posh papers don't get off lightly, either. 'What is the differ- ence between, say, the Telegraph or Times straying into Europhobia and the tabloids? There are long words and short words, but they all say the same thing. Just because the journalists holiday in Tuscany and have a good knowledge of French wine and speak fluent Catalan, or whatev- er, doesn't mean that they are not con- tributing to a poisoned atmosphere.' My own berth, the Independent, is surely above reproach, I add smugly. A steadily pro-European newspaper, with a balanced spread of views on European matters • • . 'Ha!' says Mr Kinnock. 'I complained just the other day about one of your colum- nists describing the Commission as "cor- rupt", and someone wrote that I have two limousines and eat subsidised lobster in the canteen.'

Oh dear, let's leave it there. No paper, it seems, is quite onside enough to please the Commission's vice-president. But could it not be that this crusade is counter-productive? It Makes the press seem inordinately important in determining the government's European 'This stuff really matters,' he says fiercely. 'If the public is fed a diet of myths about Europe, of course attitudes are affect- ed. There is an environment of mythology. It seeps into every aspect of the debate. And, even if nobody were listening to or printing What I say, I would still get up and say to sec- tions of the press, "You're telling lies." It might, of course, just encourage the chief offenders to redouble their efforts to annoy. 'There is a time when you cal- culate that not counter-attacking is the greater risk. What else can we do? Just sit there and take all this. . . . [he checks himself masterfully] All this. If we do nothing, it will get worse. The Sun and the Mail will tell more horror stories and use more extreme language, and the tor- rent of myths will continue because no one ever corrects it.'

This is no longer business. It is very, very personal. Talking to Neil Kinnock, one starts out having a conversation with a senior representative of the European Com- mission and ends up having one with the former leader of the Labour party. Memo- ries of the tabloid war of attrition on his election bids haunt him. 'Yes,' he admits, 'I am sensitive to that. I know what the press is doing on this because they did it to me. They weren't the sole reason I lost, but they didn't impart the sweet smell of success either. I don't want to see them do the same thing to something as important and perma- nent as our relations with Europe.'

The failed elections meander through the conversation, chilly spectral echoes of vanquished hopes. His bullish striving for the European cause feels very much like a case of transference from the old wars against Thatcher and Major, although he appears strangely surprised by the connec- tion. 'I'm a bit floored by that line of ques- tioning,' he says. A few moments of brooding silence follow — not even a stray `bloody'. 'Look,' he says, 'I've met these old politicians doing their Marlon Brando bit, "I could have been a contender", and all of that. I decided not to be like that. It's something I've locked the door on. You can't be perpetually out for revenge or some way of making good old wounds. It gets you all twisted up inside.' Something in the way he expels this last sentence, almost painfully, tells us that the untwisting has not come easily. In my notepad I have scribbled a final question about why his commitment to Europe and the euro has become so all-consumingly important to him. But he has just given the answer. It's the big battle he can still fight, now that the Labour party's battles belong to others. The euro is so many things to so many people. To Neil Kinnock, it's a war to be won; partly, perhaps, to make up for the wars he lost. 'Oh yes,' he says. 'There'll be a hell of a fight.' The thought cheers him. 'I find fights irresistible.'

Anne McElvoy is associate editor of the Independent. Sarah Helm on the truth of a Euromyth, p. 26.

The one on your front near-side is completely bald.'

Previous page

Previous page