A PAGODA OF SKULLS

China supported the Khmer Rouge, but so President Jiang's visit to Cambodia

Phnom Penh THERE has been a nice symmetry in their schedules. While President Clinton has been in Vietnam, President Jiang Zemin of China has been visiting Cambodia. As I landed last Saturday morning at Phnom Penh's Pochentong airport, workmen were erecting huge portraits of the Chinese leader, as well as a gigantic banner which said: 'LONG LIVE Tim BONS [sic] OF FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA AND THE PEOPLES REPUBLIC OF CHINA.' Two days later I was actually in Siem Reap, an hour's flight north-west of Phnom Penh and the jumping-off point for a visit to Angkor Wat, when President Jiang arrived in the town. The dusty streets were filled with schoolchildren waving banners and pictures of Jiang, and every few minutes a truck brought in another load of flag-waving farmers from the countryside.

Of course, it is easy to get caught up in the spirit of the occasion. The blue-and- red Cambodian flag with its central emblem of the great Angkor Wat temple is an attractive sight when waved by hun- dreds of fresh-faced Khmers on a sunny, not-too-hot November day. There was a festival mood in the air. But I couldn't help thinking, as I watched, of the deep irony inherent in Jiang's visit to Cambodia.

The fact is that China supported Saroth Sar (as Pol Pot was first called) from his earliest days. That support helped the Khmer Rouge win' the long war against Lon Nol in 1975, and was maintained through the years of terror until, in 1979, the Vietnamese drove Pol Pot back into the jungle. Nor did the support end there. The Chinese connection remained critical- ly important over the following decades, as the international community became increasingly involved in the fate of Cambo- dia and as the Khmer Rouge tried to win back at the negotiating table the power and prestige which they had not been able to retain through their regime of cruelty, violence and repression.

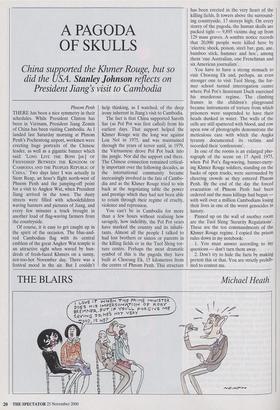

You can't be in Cambodia for more than a few hours without realising how savagely, how indelibly, the Pol Pot years have marked the country and its inhabi- tants. Almost all the people I talked to had lost brothers or sisters or parents in the killing fields or in the Tuol Sleng tor- ture centre. Perhaps the most dramatic symbol of this is the pagoda they have built at Choeung Ek, 15 kilometres from the centre of Phnom Penh. This structure has been erected in the very heart of the killing fields. It towers above the surround- ing countryside, 17 storeys high. On every storey of the pagoda, the human skulls are packed tight — 9,895 victims dug up from 129 mass graves. A sombre notice records that 20,000 people were killed here by `electric shock, poison, steel bar, gun, axe, bamboo stick, hammer and hoe', among them 'one Australian, one Frenchman and six American journalists'.

You have to have a strong stomach to visit Choeung Ek and, perhaps, an even stronger one to visit Tuol Sleng, the for- mer school turned interrogation centre where Pol Pot's lieutenant Duch exercised his murderous regime. The climbing frames in the children's playground became instruments of torture from which prisoners were suspended to have their heads dunked in water. The walls of the cells are still spattered with blood, and row upon row of photographs demonstrate the meticulous care with which the Angka tyranny documented its victims and recorded their 'confessions'.

In one of the rooms is an enlarged pho- tograph of the scene on 17 April 1975, when Pol Pot's flag-waving, banner-carry- ing Khmer Rouge soldiers, standing on the backs of open trucks, were surrounded by cheering crowds as they entered Phnom Penh. By the end of the day the forced evacuation of Phnom Penh had been ordered and the mass killings had begun with well over a million Cambodians losing their lives in one of the worst genocides in history.

Pinned up on the wall of another room are the Tuol Sleng 'Security Regulations'. These are the ten commandments of the Khmer Rouge regime. I copied the prison rules down in my notebook: 1. You must answer according to my questions — don't turn them away.

2. Don't try to hide the facts by making pretext this or that. You are strictly prohib- ited to contest me. 3. Don't be a fool for you are a chap who dare to thwart the revolution.

4. You must immediately answer my questions without wasting time to reflect.

5. Don't tell me about your immoralities or the essence of the revolution.

6. While getting lashes or electrification you must not cry at all. 7. Do nothing, sit still and wait for my orders. When I ask you to do something, you must do it right away without protest. 8. Don't make protests about Kam- puchea Krom in order to hide your jaw of traitor.

9. If you don't follow the above rules, you shall get many lashes of electric wire.

10. If you disobey any point of my regu- lations, you shall get either ten lashes or five shocks of electric discharge.

As we left Tuol Sleng, my driver told me that both his parents had been tortured to death there.

Choeung Ek, Tuol Sleng, the stories ordinary people tell you of their own or their relatives' suffering — these things are quite enough to put President Jiang's visit to Cambodia in a different light. If you want to raise human-rights issues with China, you don't have to limit them to Tiananmen Square. What China has done by proxy counts too. To be fair, China has never sought to disguise its support (then and now) for the Khmer Rouge. The support of the United States for the Khmer Rouge is far more `It's a nubile phone.'

nebulous. History's airbrush has been at work overtime. Human-rights campaigners in the USA have conveniently forgotten that people like Zbigniew Brzezinski, Pres- ident Carter's national security adviser, actively promoted US support of the China-backed Khmer Rouge as a counter- weight to Soviet support of Vietnam. Even after 1979, when the Cambodian atrocities had come fully to light and Pol Pot had retired to the jungles along the Thai bor- der, the Khmer Rouge still had friends at a very high level in the US administration, with the USA insisting that they should be in any future Cambodian coalition — as indeed they are today.

The reality is that US and Chinese inter- ests, as regards the Khmer Rouge, have long converged far more than they diverged, a fact which President Clinton's historic visit to Vietnam this week will not be able to obscure.

Even though there is no escaping the almost palpable reek of Cambodia's past, it is nonetheless possible to sense a brighter future. 1 discovered, for example, that there had, after all, been some protests on the streets about President's Jiang's visit. Serious efforts are being made to stamp out crime and corruption. There are even moves afoot to bring some of the worst Khmer Rouge criminals at last to trial.

My visit to Phnom Penh coincided with the three-day Water Festival, an event which marks a hydraulic phenomenon as the Tonle Sap river (which joins the Mekong more or less in front of the Cam- bodiana Hotel) reverses itself and flows in the opposite direction. I had a grand- stand view of enormously long barges, each powered by scores of colourfully dressed rowers, thrashing up and down the river in some gigantic Asiatic Henley Regatta while the cheerful, smiling crowds congregated along the quays in tens of thousands. Ten years ago this fes- tival was still banned. Today it is a time for national rejoicing. If rivers can reverse direction, who knows what other miracles may happen? We may even see peace and prosperity return to this antique land.

Previous page

Previous page