Exhibitions 2

Conflation of opposites

Martin Gayford There are certain artists — just as inter- esting if not more so than the others who are out of tune with their times. One such was Lorenzo Lotto, never happy with- in the skin of a classicising Italian Renais- sance artist. Another, closer to our own day, was the American Philip Guston, sub- ject of an exhibition at the Pompidou Cen- tre. It was only towards the end of his life, when he was already well into his fifties, that he found his own true self as a painter — and in doing so made 'late Philip Gus- ton' one of the key bodies of work in late- 20th-century art.

The show in New York in 1970, in which Guston revealed his new work, caught just about everybody by surprise. Robert Hugh- es, writing in the second edition of The Shock of the New, gracefully admitted that he for one had not understood these new Gustons at all. 'Every critic has his or her embarrassments, judgments flatly wrong, meanings missed by a country mile.' (He speaks there for all of us, like political prognostication, art criticism is a high-risk enterprise.) But then that 1970 Guston show must have been an extremely difficult one to get right.

Guston was a known quantity, a painter of delicate abstractions, shimmering mists of colour made up of many small strokes even if those veils had been getting rather darker and lumpier of late, people knew more or less what to expect. And here he was exhibiting paintings of shoes, hairy legs, hooded Ku Klux Klansmen, dustbin lids, cigars and clocks, all executed in a style that might be dubbed comic-book apocalyptic. And yet those, and the similar paintings that followed in the next decade before his death, are the paintings by which he will be remembered.

Guston was of the generation that pro- duced the Abstract Expressionists (though he himself preferred the description New York School). More, he was in the absolute social and artistic heart of that movement. In Los Angeles, where he grew up, his boy- hood friend at school was Jackson Pollock. For a decade and more he himself was a cel- ebrated abstract painter of the New York School. But, as one can see from this exhibi- tion, abstraction — whether it should be called expressionist or not — was never quite right for Guston, was never really him.

Indeed, the more abstract his paintings are, the weaker they look — as is clear at a glance today, although, such is the power of the zeitgeist, in the 1950s they were among the most widely imitated art around. The term 'veil' is often applied to abstract paintings; in Guston's case it seems exactly right. In his abstractions it looks as though something has been cov- ered up. You can see it disappearing as he moved into abstraction in 'The Tormen- tors' (1947-48), and you can see it surfac- ing in the dark masses, like rocks beneath a choppy sea, that appear in his mid-Sixties paintings (`The Year', for example).

Something similar is true of Jackson Pol- lock. Beneath his celebrated drip paintings there seems to be submerged subject mat- ter — dancing figures, a stampede. But the more abstract Pollock's work became, the better — the freer, the wilder, the stronger. With Guston it was the opposite — they got milder, gentler, more tasteful.

One of the innumerable ways in which the art of the 20th century could be under- stood is as a dialogue between two tenden- cies. On the one hand there was an idealistic pull towards simplicity and purity — Malevich, Mondrian, Rothko, minimal- ism. On the other hand, the nuts and bolts — or in Guston's case the hobnail boots of the world keep getting reinserted into the mixture. Duchamp did that with actual objects such as bottle racks and urinals, so too did Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Warhol, who fitted items such as soup cans, flags and car tyres into their art.

As with all such distinctions, many peo- ple have a bit of both tendencies. But Gus- ton comes out as fundamentally a fag ends, dustbins, nuts and bolts man. What was submerged in his paintings in the late For- ties was more or less what re-emerged 20 years later — shoes, Klansmen, urban wastelands. He had been painting hooded figures, and violent scenes from 1930, when he was 18. In the Thirties, like many of his Depression generation, he tried hard to create socially committed art. He got fur- ther than most — than Pollock for example — creating a number of large murals in housing schemes and so forth. These were praised at the time, but from photographs — the originals, it seems, have been defaced or long disappeared — one sus- pects that they would have dated badly.

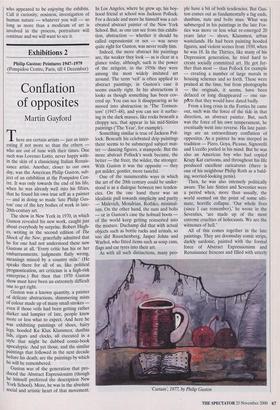

From a long crisis in the Forties he came out, such was the force of the tide in that direction, an abstract painter. But, such was the force of his own temperament, he eventually went into reverse. His late paint- ings are an extraordinary conflation of opposites. As a painter he was steeped in tradition — Piero, Goya, Picasso, Signorelli and Uccello jostled in his mind. But he was also an American boy who had copied Krazy Kat cartoons, and throughout his life produced excellent caricatures (there is one of his neighbour Philip Roth as a bald- ing, worried-looking penis).

Then, he was also intensely politically aware. The late Sixties and Seventies were a period when, more than usually, the world seemed on the point of some ulti- mate, horrific collapse. 'Our whole lives (since I can remember),' he wrote in the Seventies, 'are made up of the most extreme cruelties of holocausts. We are the witnesses of hell.'

All of this comes together in the late paintings. They are doomsday comic strips, darkly sardonic, painted with the formal force of Abstract Expressionism and Renaissance frescoes and filled with utterly `Curtain; 1977, by Philip Guston personal imagery. Those ubiquitous shoes are supposed to derive from the horseshoes in Uccello's 'Battle of San Romano', but also from the secondhand goods in which his Russian-Jewish immigrant father dealt. What the shoes mean, and what the paint- ings themselves mean, is beyond simple decoding. As with Pollock's drip paintings, there have been plenty of imitators, but nothing really much like them.

Previous page

Previous page